Parents rely on neighbors, friends, family members and other caregivers to provide in-home temporary caregiver support, frequently referred to as “babysitting,” for their children while they attend meetings, run errands, and have some “couple” time away from routine family responsibilities. This can be a daunting challenge for parents of youth and adolescents with ASD for various reasons. Most typical individuals in this age group do not “require” in home temporary care; therefore, there may be a lack of “sitters” available to care for this age group. Those available may be hesitant to care for an adolescent that is near the same age as them, and may be apprehensive based on their lack of knowledge of how to support an individual who may exhibit communication and behavior challenges. Yet these individuals on the spectrum cannot be left alone and more often than not, parents refrain from going out for lack of an appropriate “sitter” for their adolescent.

The following experience from a first-year teacher illustrates this difficulty:

During Ms. Porter’s first open house of her first year of teaching, she had planned to welcome parents into her classroom to inform them about the life skills and vocational curriculum she would be using to teach their adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. To her surprise, only 1 parent attended the Open House, bringing along her 2 children. The parent immediately apologized to Ms. Porter saying “I am so sorry for bringing Johnny and Avery, but I have been unable to find a babysitter capable of caring for Johnny while I am out. Avery is okay with any babysitter, but because of Johnny’s age, size and behaviors, it is just too hard.” Ms. Porter soon realized that this was true for many of her student’s parents, and why many of her parents were unable to attend that Open House.

Social interaction and communication challenges associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may result in an increased use of disruptive and non-functional behaviors, especially in the context of novel situations, such as those experienced with a temporary caregiver giving support, like a babysitter. The difficulty in understanding the function of these behaviors and their variability lead to frustration for those caring for children of all ages with ASD (McCann, Bull, & Winzenberg, 2015; Pottie & Ingram, 2008). Not only does this impact the temporary caregiver’s ability to be supportive, it results in additional stress for the parents. Mothers of individuals with ASD report higher levels of caregiver burden than parents of typically developing individuals and higher levels of stress or depression than mothers of individuals with other developmental disabilities; including Down Syndrome (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2008; Pisula, 2007; Roper, et al., 2014). The behavioral difficulties of individuals with ASD play a role in the increased level of need for support for these parents (Siklos & Kerns, 2006). Mothers and fathers of young children with autism also report higher levels of stress related to their parenting responsibilities linked to these challenges (Rivard, Terroux, Parent-Boursier, & Mercier, 2014). Fortunately, we know that families who receive more respite care for their youngsters with ASD report lower levels of stress. Therefore, an increase in respite type services (i.e. in-home temporary support, babysitters) for families of individuals with ASD is indicated (Harper et al., 2013).

Parents have limited access to resources to help them cope with behaviors and communication difficulties due to extreme cost and time of intervention (Davis & Carter, 2008). As a result, increased resources to provide support within the home and community environments is needed (Schleien, Miller, Walton, & Pruett, 2014). Services such as baby-sitting and/or in-home care for individuals with ASD are increasingly being recommended for these families (Siklos & Kerns, 2006) and this additional in-home care needs to be from trained and trusted individuals (Thompson & Emira, 2011). One approach would be to provide training opportunities for both potential temporary caregivers and families to learn about ways they can support their young child or young adult (Cridland, Jones, Magee, & Caputi, 2014). Providing training and workshops for the primary and secondary caregivers, including in-home care providers, is a unique way to teach these individuals the essential strategies to use in the home during short-term care.

Sit for Autism

Referred to as Sit for Autism, our program was designed to teach families, caregivers, babysitters, and those who may provide temporary caregiver support, general information regarding autism spectrum disorders. Content of the training emphasizes strengths and challenges associated with autism, common characteristics of individuals with autism, and explanation of key evidence-based practices to engage individuals with autism and reduce their problematic behaviors during short-term care.

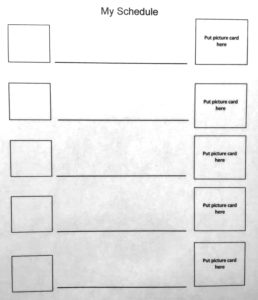

The Sit for Autism program consists of one, 2 hour training session that blends lecture with hands-on activities. The initial part of the training involves the use of a PowerPoint presentation that shares information focusing on the common social, behavior, and communication characteristics of individuals with ASD. The second part of the training session includes instruction and modeling of the implementation of 4 evidence-based practices that may be used in the home or community setting. Participants are given a kit that contains these tools, including, a visual support for the use of the “Premack Principle” (Premack, 1959), visual schedules, a self-management tool to assist with transition, and a visual support choice board (Wong, et al., 2013). Example scenarios are reviewed and each participant is given the opportunity to practice: (a) An individual may adhere to a specific routine at home that is unfamiliar to the caregiver giving support. The parent may support their child by arranging a visual schedule designed with pictures or written words of the activities that he or she will participate in while the parent is away. The caregiver is instructed to remove or erase each activity as it is completed to assist the individual in understanding what will be next as well as to support awareness that the parent will soon be home. (b) In a situation where an individual should complete a task of low preference such as a household chore, the caregiver is encouraged to use a First-Then card, writing “First vacuum, Then (favorite activity).” The caregiver is instructed to show this visual to the individual right before it is time to begin their vacuuming task. The caregiver would say “First vacuum, Then TV” while pointing to the visual support. Provided that the individual wants to watch a particular TV show, this should serve to encourage and motivate the individual to engage in the household task of vacuuming. (c) For time limited activities or those of least interest to an individual, the temporary caregiver giving support is taught to use either a sound or visual timer to indicate when the activity will or must end. As soon as the timer rings, the individual is allowed to end the activity. (d) An individual may have increased anxiety with the parent away and struggle to access language to request choice. The temporary caregiver is encouraged to use a choice board that will have a visual representation of all of the activities, or food, that may be selected by the individual while the parent is away.

- Visual Schedule

- Visual Choice Board

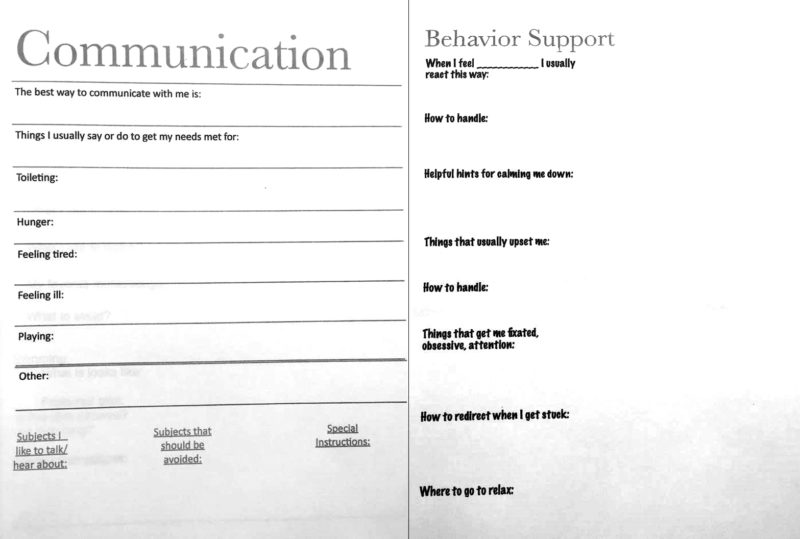

In addition to the evidence-based practice tools, the training provides the participants with a booklet referred to as the “Sit-Kit.” This booklet is completed by the parent and includes critical information about the individual that will further support the caregiver in supporting the individual while the parent is away. The “Sit-Kit” is a modified version of a booklet designed by the Connecticut Lifespan Respite Coalition, Inc (2008), with permission from Joy Liebeskind. This modified version adds components that are critical for parents of individuals with ASD.

Sample page from “Sit Kit” Manual

Over the course of a two-year period, a total of 112 participants of various ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds were included in the training sessions, including parents, family members, caregivers, and babysitters. During its pilot year, pre and post survey outcomes revealed that all participants were “satisfied” or “highly satisfied” with the training program (83% highly satisfied). All participants would recommend this training program to others. Sit for Autism can be an effective training program for the family members, service providers, and caregivers of individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

Programs such as this type of training can provide those additional supports needed for families and community members to cope with and manage the severe and unique needs of individuals with ASD of any age.

Funding provided by the CT Department of Public Health project, the CT Collaborative for Improving Services for Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and other Developmental Disabilities (DD). State Implementation Grants for Improving Services for Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Other Developmental Disabilities. Announcement number: HRSA -11-071

Kimberly Bean, EdD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Special Education and Reading Southern CT State University. Barbara Cook, EdD, CCC-SLP, is Assistant Professor, Department of Communication Disorders, Southern CT State University. Ruth Eren, EdD, is the Dorothy W. Goodwin Endowed Chair, Department of Special Education and Reading; Director of the Center of Excellence on ASD, Southern CT State University. Karen Meers, PhD, BCBA, Center of Excellence on ASD, Southern Connecticut State University.

For more information about Sit for Autism, contact Dr. Kimberly Bean at beank2@southernct.edu or the SCSU Center of Excellence on Autism Spectrum Disorders at https://www.southernct.edu/academics/schools/education/asd-center/.

References

Abbeduto, L., Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Krauss, M. W., Osmond, G., & Murphy, M. M. (2004). Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, down syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 109, 237–254.

Connecticut Lifespan Respite Coalition, Inc. (2008). Get creative about respite: A parent’s guide. Retrieved from http://www.ct.gov/dph/lib/dph/family_health/children_and_youth/pdf/59684_parents_guide.pdf

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Magee, C. A., & Caputi, P. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: A review of the utility of family systems approaches. Autism, 18(3), 213-222.

Davis, K & Gavidia-Payne, S. (2009). The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the quality of life in families of young children with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(2): 153-162.

Davis, N., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291.

Harper, A., Dyches, T., Harper, J., Roper, S., & South, M. (2013). Respite Care, Marital Quality, and Stress in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 43(11), 2604-2616

Lee, L. C., Harrington, R. A., Louie, B. B., & Newschaffer, C. J. (2008). Children with autism: quality of life and parental concerns. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1147–1160.

McCann, D., Bull, R., & Winzenberg, T. (2015). Sleep deprivation in parents caring for children with complex needs at home: A mixed methods systematic review. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(1), 86-118.

Pisula, E. (2007). A comparative study of stress profiles in mothers of children with autism and those of children with Down syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 274-278.

Pottie, C., & Ingram, K. (2008). Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: A multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 855-864.

Premack, D. (1959). Toward empirical behavior laws. I. positive reinforcement. Psychology Review, 66(4), 219–233

Rivard, M., Terroux, A., Parent-Boursier, C., & Mercier, C. (2014). Determinants of Stress in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1609-1620.

Roper, S. O., Allred, D. W., Mandleco, B., Freeborn, D., & Dyches, T. (2014). Caregiver burden and sibling relationships in families raising children with disabilities and typically developing children. Families, Systems & Health: The Journal of Collaborative Family Healthcare, 32(2), 241.

Schleien, S. J., Miller, K. D., Walton, G., & Pruett, S. (2014). Parent perspectives of barriers to child participation in recreational activities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 48(1), 61.

Siklos, S., & Kerns, K. A. (2006). Assessing need for social support in parents of children with autism and down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(7), 921-921-33.

Thompson, D., & Emira, M. (2011). “They say every child matters, but they don’t”: An investigation into parental and career perceptions of access to leisure facilities and respite care for children and young people with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) or attention deficit, hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Disability & Society, 26, 65–78.

Wong, C., Odom, S.L., Hume, K., Cox, A.W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., … & Schultz, T.R. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.