People with disabilities face many documented barriers to full inclusion in society. According to Article 3 of The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, one of the primary barriers is the general public’s attitudes towards people with disabilities. (Merrells, Buchanan & Waters, 2018). Discrimination experienced by individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) limits their access to social and recreational activities, employment opportunities, living accommodations, and community resources. Social stigma may also contribute to co-occurring depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions (Botha & Frost, 2018). It is also important to note intersectionality of race, ethnicity and disability. The impact of discrimination is even higher for these groups (Hassiotis, 2020).

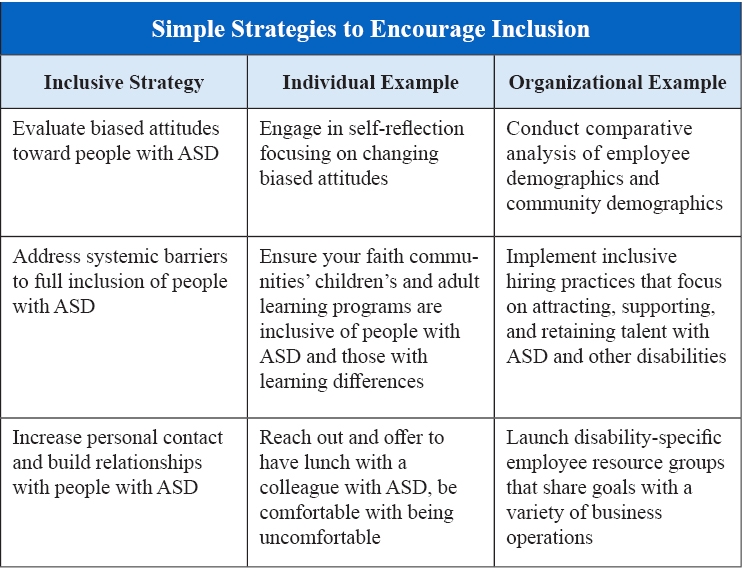

To improve public attitudes and reduce stigma change must occur at the personal and organizational levels (Fisher & Purcal, 2017). Every community member can promote inclusion by taking steps at the individual level. Self-reflection is the first step in addressing individual bias. That requires awareness of attitudes that guide thoughts, behavior, and feelings. An example of individual bias is social avoidance: community members avoid a person with a disability because of their social discomfort. For many, that is the result of having no previous contact with people with disabilities. (Slater, 2020). Developing interpersonal relationships with individuals with ASD is essential to redress these biases. Only through personal contact with a neighbor, a colleague, a family member, or through the development of a friendship can social avoidance be mediated and these biases be confronted and changed.

Stereotypes stigmatize people with ASD. For example, it’s falsely believed that people with ASD need to be taken care of, they drain society resources, they are weird. Sadly, these beliefs contribute to the lack of equitable options for employment, housing, and social engagement for many individuals with ASD. Confronting stereotypes through self-reflection is an uncomfortable but crucial step in the process of promoting inclusive communities (Slater, 2020).

The stereotype that people with ASD prefer to perform repetitive tasks at work has negative effects too. If an employer believes an employee with ASD only has an aptitude for repetitive tasks, they’ll be overlooking that person’s full potential. For example, Charles, an academic, most apt at conducting complex analyses of literature, accepted a job he was offered because he needed to work. The job involved the completion of repetitive tasks. He was not successful at the job he was hired for and eventually lost the job due to poor performance. His next employer understood his specific interests and abilities, and took the time to meet and listen before forming an opinion on how he would fit into their organization. In his current job he provides analyses of research and academic literature to team members. He has never been happier. People with ASD can thrive when people confront personal bias and value diverse backgrounds, choices, preferences, skills, and abilities of people with ASD.

Personal attitudes and beliefs are not the only barriers to inclusion. Change must also occur at the organizational level (Fisher & Purcal, 2017). Organizations have tremendous influence over the attitudes and beliefs of their communities. For example, businesses have the power to influence inclusion on a massive scale through a variety of strategies. They include inclusive hiring practices, issuing public statements about inclusive hiring, partnering with disability service organizations for public service announcements, and including people with ASD as stakeholders in decision-making. These efforts increase the personal contact of employees and customers with individuals with ASD, further reducing stigma through the development of relationships between people with and without ASD. Organizations make decisions about who to include and empower every day.

Are businesses, faith and community organizations, social groups, educational institutions, and government agencies creating opportunities for people with ASD to contribute? These are essential questions not asked often enough. Leaders in these organizations can learn about the benefits of inclusion, through full representation from the community, including people with ASD. Listening to and empowering people with ASD is a choice (Risley, 1996).

The most important thing anyone can do to create inclusive communities is to have friendships and relationships with people with disabilities. Choose to listen and learn from them. Embrace the feeling of discomfort that comes with change. Use the experience to advocate for inclusion. Inspire others to be the change you want to see in the world.

Brad Walker

John Bryson, MS Ed, CESP

John Bryson, MS Ed, CESP, is Senior Manager, Corporate Consulting, and Brad Walker is Vice President, Community Living Supports at NEXT for AUTISM. Contact John Bryson by e-mail at jbryson@nextforautism.org. Contact Brad Walker by e-mail at bwalker@nextforautism.org. NEXT for AUTISM can be found on the web at www.nextforautism.org.

References

Botha, M., & Frost, D. M. (2018). Extending the Minority Stress Model to Understand Mental Health Problems Experienced by the Autistic Population. Society and Mental Health, 10(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318804297

Fisher, K. R., & Purcal, C. (2017). Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(2), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1222303

Hassiotis, A. (2020). The Intersectionality of Ethnicity/race and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Impact on Health Profiles, Service Access and Mortality. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(3), 171–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2020.1790702

Merrells, J., Buchanan, A., & Waters, R. (2017). The experience of social inclusion for people with intellectual disability within community recreational programs: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1283684

Risley, T. R. (1996). Get a life! In L. K. Koegel Jr., R. L. Koegel, & G. Dunlap, Positive behavioral support (pp. 425-437). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Slater, P., McConkey, R., Smith, A., Dubois, L., & Shellard, A. (2020). Public attitudes to the rights and community inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities: A transnational study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 105, 103754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103754