Moving out of a family home is often one of the biggest decisions in a young person’s life, representing a turn towards independence and a chance to create their own space in the world. While this is a big step for any individual, it can be especially challenging for individuals with disabilities. These individuals and their families are tasked with not only finding a home, but also securing caregivers or other forms of support in the process. Far too many people seeking supportive housing end up on a waiting list for months or even years due to limited availability. This issue was further highlighted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many individuals with disabilities were forced to self-isolate but still required support and assistance from their families.

NY State Assemblyman

Angelo Santabarbara

New York has one of the highest estimated adult populations with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the country at more than 340,000 individuals.1 Currently, the primary housing option for these individuals is community-based housing in which they share a group home with other adults. Families of those living in community housing, however, have expressed concern with limited options for family caregivers to provide the individualized support necessary to address their specific needs.2 As the father of a son who lives with ASD, this is deeply concerning, and I’m certain that this concern is shared by other parents thinking about their child’s future.

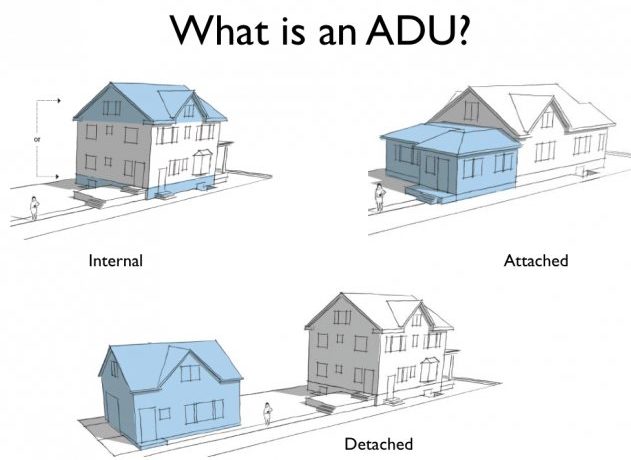

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) are living spaces that share a single-family lot with a larger dwelling, mainly located within, attached to or detached from the main residence, generally containing a kitchen, bathroom and bedroom. ADUs were very common before the increase of suburban single-family homes.

In recent years the demand for ADUs has increased across the country among people of all ages and can be part of the solution here in New York State. ADUs could serve as independent housing for a family member with a developmental disability.3 This would allow disabled individuals to live on the same property as their family members or caregiver, providing them with an easy avenue for support and caregiving while still having their own independent spaces.

ADUs can also be an option for those who hope to remain in their homes as they age and want a different living arrangement that allows them to stay in their communities. Many older New Yorkers also often live in homes without accessibility needs. ADUs can be built with those needs in mind, allowing people to age in place with a family member or caregiver living nearby with the opportunity to downsize to a separate, more accessible home on their own property.

In the New York State Assembly I’ve proposed a bill that would allow homeowners to access an interest-free loan program for up to $50,000 or 50% of construction costs to add an accessory unit of up to two bedrooms to their home (A.1410 of 2020).

According to a 2018 study conducted by AARP, 84% of families with a disabled relative would consider building an ADU to care for them.4 Unfortunately, cost is often a prohibiting factor, with average costs ranging from $50,000 for an internal ADU to $150,000 for a detached ADU. They are usually financed through a combination of savings, a second mortgage or a home equity line of credit.5 This challenge calls for proposals to help cut down on these costs by offering an interest-free, potentially deferred-payment loan for the construction of an ADU. This would ease the financial burden on families while also giving them an incentive to look into different methods of care and support other than group homes.

The ADUs covered by the proposal I have introduced could also be used as an alternative to assisted living or nursing home options. For elderly adults diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia, the physical and cognitive changes associated with the disease require the eventual need for 24-hour supervision and an increasing need for assistance with daily living and activities.6

More communities are now allowing ADUs that adhere to local size and lot placement limits in residential areas, as long as they meet to local zoning requirements. Other states including New Hampshire, Vermont, Oregon and Washington have already passed laws requiring most or all cities and counties to allow ADUs, with some restrictions. Others have applied already existing regulations for the construction of ADUs. But some local governments apply additional rules to ADUs.

It is important to ensure that the most vulnerable members of our community are not forgotten or left behind. People want to live in their own communities near family and friends. As we begin the COVID-19 recovery process, we need to rethink housing and find better options, like ADUs. Making ADUs more accessible to New York families will help provide our loved ones the ability to live independently, but with a built-in safety net.

As the chair of the New York State Assembly Subcommittee on Autism Spectrum Disorders, I welcome any and all questions and concerns readers may have. Please feel free to contact my office at 518-382-2941 or send me an email at SantabarbaraA@nyassembly.gov. You can also find more information on my website at www.nyassembly.gov/Santabarbara.

Footnotes

- www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/features/adults-living-with-autism-spectrum-disorder.html

- www.nyassembly.gov/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=A01410&term=2019&Summary=Y&Memo=Y

- Ibid.

- www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/livable-communities/livable-documents/documents-2019/ADU-guide-web-singles-071619.pdf

- Ibid.

6. www.health.ny.gov/statistics/brfss/reports/docs/2021-02_brfss_cognitive_decline.pdf

[…] speaking of autonomy, ADUs are also a perfect way to allow your family members with special needs to have some independence while also being close enough to offer […]

[…] the goal that people with disabilities should be enabled to live independently. According to a 2018 study, 84 per cent of families with a disabled relative in the United States would consider building an […]