An adult on the spectrum can accomplish or achieve everything his/her/their cohort who is not on the spectrum has accomplished or achieved, and yet not be rewarded with that same level of independence and autonomy for his/her/their efforts (Cheak-Zamora, Tait & Coleman, 2022). Although young adults are living at home longer than ever after high school graduation, the adult who is on the spectrum does not see an end point in the same way that others do (Furfaro, 2018). Who would not be frustrated and depressed to do what society has prescribed as the path to independence, and yet find oneself stalled in what seems to be a regressed and unenviable position?

Many of us have defined living outside our family of origin, be it on our own, with roommates, or in a relationship as the definition of adulthood. Many of the clients I work with have in common their defining achievement as being the beginning of adulthood. Those clients are, therefore, thwarted in their efforts to become an “adult” as they are defining it and as it is reinforced by our culture. The establishment of one’s own household, in whatever form it may take, has meaning for the individual on the move and for everyone around him/her/them as well.

Reality is unmercifully creating blocks for my clients to achieve this. First, there is the financial reality that is unsurmountable. I have worked with several clients who were employed full-time, were valued employees, yet could not possibly earn what would be required to support themselves. I have also worked with clients who are in prevocational training and internships. They are exactly where they should be and they can feel their own progress and development, but they are not earning any compensation for that effort. I also have clients who are on waiting lists for supportive housing. Here, there is hope to achieve the goal of living outside of their family of origin, albeit they have had to cope with being on staggeringly long waiting lists where movement is unpredictable. This brings parents some peace of mind, but it does not help a 25-year-old who feels like they have not left their childhood bedroom, both literally and figuratively.

In consideration of these factors, I have placed an emphasis, when I work with these clients, on an “adultification” of the present. While we cannot create jobs that pay a living wage or turn internships into competitive employment, there are other psychological interventions we can construct that liberate one from childhood. Interestingly, I had a client whose parents set him up in an apartment that they owned in an urban area and they lived several miles away in a suburban setting. He would have been the envy of many of my other clients yet he was miserable. He felt his parents were intrusive and controlling and he lamented, “I might as well move back home – I live in a bedroom that is 10 miles away from the rest of my house.” The idea of how to live in the world as an adult was even an issue for this client.

One of the most immediate ways to create a different psychological space in the same square footage is to redecorate. Depending on one’s budget this can range from painting the walls to buying new furniture. The question becomes how this space goes from a childhood bedroom to one that reflects an adult sensibility. With one client, with his parents’ support, we worked on thinking of his room as a studio apartment and he went from a twin bed to a couch that opens. Treasures and mementos from the past can be safely stored away and not be on display any longer. Rituals that mark developmental achievements have emotional meaning and it is possible to have a “housewarming” party that unveils the new space to friends and family. Perhaps a party where people bring a gift and alcohol could be served.

It is also essential that the individual seeking adulthood in their childhood home is integrated into helping the household function. Preferably, the role or chore that the individual does is something that others cannot perform. One of my clients who lives with his aging parents learned to change the HVAC filters – a task that his parents found physically challenging. Now his parents joke that if it were not for their son, they would not be breathing in fresh air. To live with others and to not have responsibilities is infantilizing and provides no opportunity for building and strengthening skills that are necessary for future independence and autonomy. I have a young adult client living with his family who is working hard to “be on top of the dishwasher” – his job is to load it, run it, put items away, and for his other family members not to have to worry about it. His mother told us in a family session that although she is certainly capable of handling the dishwasher on her own, it has meaning to her when she sees the effort that her son is putting into mastering this task, and as a result she considers other ways to give him independence and responsibility. Of course, there is no reason why most clients cannot do their own laundry, whether it be somewhere in the house, in the basement of the apartment building, or the corner laundromat.

Most of the young adult and adult autistic clients I work with who live at home have parents paying for some aspect of their life that is essential in our culture today, such as a cell phone. When these arrangements are made without any link to household contributions and participation, there is a lost opportunity for what I refer to as “adultification.” I worked with a client and his family recently to make this paradigm shift and to create a system wherein the client’s contributions to daily family life translated to their continuing to pay for his cell phone and video games. Different contributions had varying degrees of power in this system, and it was therapeutic for the client and the family to negotiate what that power should look like at first. The earned power in the system became currency that they would then respect with payment for his cell phone, etc. As the client stated once he accepted this new arrangement, “they are paying for it, but I am the one who is working for it.” The client’s mother wondered, when the client was initially resistant to this change, if what I suggested was too regressive for him as it sounded like the token economy systems that were part of the therapeutic school programs that he had attended for years. We discussed how that was exactly what it was, and that the idea of getting some kind of currency and empowerment for effort was the foundation of the paycheck that adults buy into in the work world. In this way of thinking, this is an adult concept as getting everything that one wants, contingent on nothing, is more the psychology of infancy and early childhood and not indicative of “adultification.”

The cliché that you are as young as you feel has relevance here. We need to consider the subjective experience of being an adult rather than defining adulthood as exclusively a chronological phenomenon. As such, there are a myriad of ways that we can support autistic clients in this “adultification” process, unrelated to what their actual living arrangement is at present.

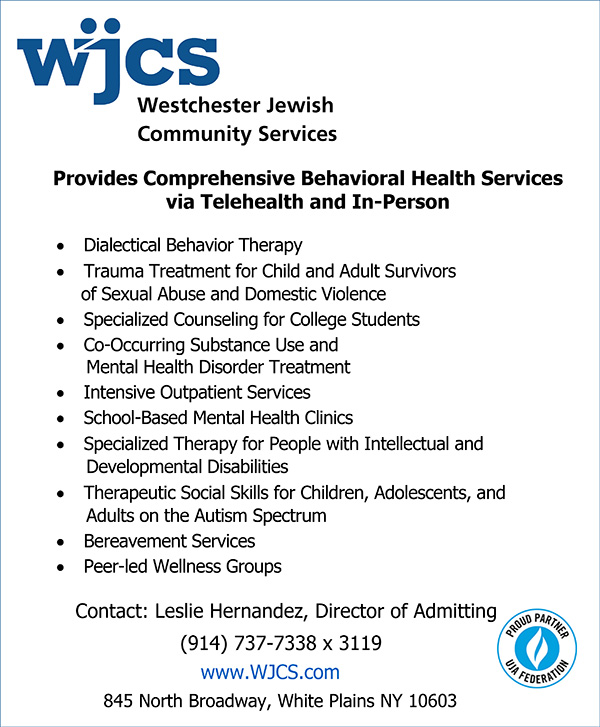

Kenneth Mann, PsyD, is Director of Outpatient Programs for the Developmentally Disabled at Westchester Jewish Community Services (WJCS). WJCS is one of the largest human service organizations in Westchester County, New York. To learn more about its 80+ programs and services, please visit www.wjcs.com.

References

Cheak-Zamora, Tait & Coleman (2022, April 14). Assessing and Promoting Independence in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34636359/

Furfaro, Hannah (2018, February 15). Jobs, Relationships Elude Adults with Autism. Spectrum. www.spectrumnews.org/news/jobs-relationships-elude-adults-autism/