It is estimated there are more than 3.5 million Americans living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the number continues to grow.1 According to CDC statistics, the prevalence of autism has increased from 1 in 150 children born in 2000 to 1 in 54 as of 2020.2 This expanding segment of the population is also likely to account for a disproportionately greater share of first responder resources, due to their greater susceptibility to accidents and injuries. A study published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2017 suggested individuals with ASD face as many as 3 times the risk of dying from unintentional injuries when compared to the general population.3 The study found the increased risk of unintentional injury is particularly high for children with ASD under the age of 15, with drowning, suffocation, and asphyxiation accounting for close to 80% of the total injury mortality in children with autism.3

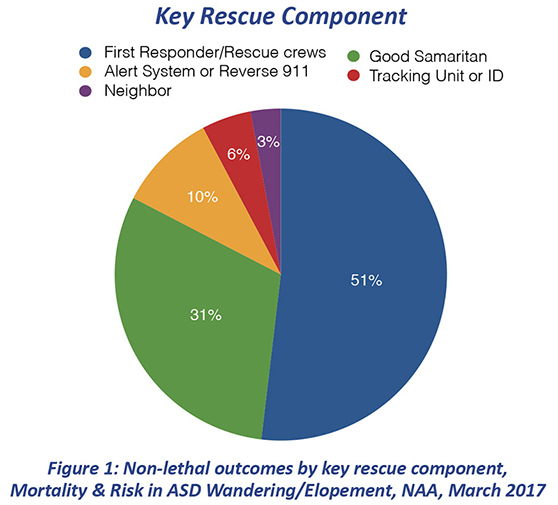

According to research published in Emergency Medicine, caregivers report 13% of their autistic children used at least one emergency service in a 2 month period, and 20% of autistic children have had encounters with law enforcement officers by the age of 2.4,5 It is not surprising then, that children with ASD have a higher likelihood of encountering first responders. The importance of these first responder encounters cannot be underestimated. In cases of elopement, for example, first responders account for the majority of rescues.

Given higher propensity for injurious events in the ASD population and the critical role first responders play in successful outcomes, it is critical for the ASD community to work more closely with first responders to increase ASD awareness, develop skills needed to effectively interpret ASD individuals’ behaviors, and to improve strategies used during these encounters and emergencies.

Educating First Responders

Although progress is being made, as seen in New Jersey where training in ASD is required through the Autism Shield program, more needs to be done to improve first responder awareness of ASD on how to efficiently and effectively manage situations involving individuals with ASD during emergencies. A 2020 study examined 13 professional databases and 28 journals and only found two articles regarding law enforcement training and ASD.6 Other research has indicated close to 75% of law enforcement officers reported no training on working with individuals with autism.7 Without proper awareness of characteristics of ASD, such as lack of eye contact, avoidance of loud sounds, or difficulty responding to commands, first responders may incorrectly assume that behaviors indicate a lack of cooperation, and consequently make decisions that result in negative outcomes.8 Misinterpretations of ASD symptoms may contribute to the rising number of incidents involving individuals with developmental or neurological differences. Research suggests specialized training in autism should focus on identification of characteristics of ASD and engagement in strategies to support people with ASD, particularly during emergencies.6 There are several initiatives who families and practitioners can take to help improve ASD awareness with their local first responders.

For parents, hosting a meet and greet event at a local police or fire station can allow children with ASD to become familiar with first responder uniforms, vehicles, K9s, and people they may encounter during an emergency. There should be consideration for parents to add their children to the local registry of children with ASD or request they start one. Taking this step could help alert police, firefighters, and paramedics who may be called to respond to emergencies at a home. This will give local authorities a chance to prepare their approach to helping with the crisis. Gary Weitzen, the executive director of Parents of Autistic Children, says that local authorities all know his son with autism and they know how to talk to him if he is ever in need of assistance.9 Take Me Home is a free program developed as part of the Autism Society’s Safe and Sound Initiative for police departments to maintain a voluntary database of individuals who need assistance if found alone in the community. Project Lifesaver and SafetyNet Tracking are two additional voluntary registry programs that are often used to register individuals with ASD.

Andrea Lavigne, PhD, BCBA

Thea Davis, MSEd, BCBA

For practitioners, conducting outreach to first responders such as police and fire stations and offering trainings can provide an additional approach to improve understanding of ASD and positively impact future encounters. Most current trainings for first responders are online, but studies suggest role playing and using behavioral skills training (BST) may be a more effective way for first responders to learn practical skills in gaining cooperation and having successful interactions with individuals with ASD in dangerous situations. Providing in person live trainings allow for first responders to ask questions and discuss case studies on common scenarios they may encounter during emergencies with an individual with ASD.10 Giving examples of behaviors that individuals may exhibit can help first responders recognize the individual as someone who may have ASD and not interpret the behaviors as a hazard or disobedience towards the first responder. For example, providing time for the individual with ASD to process and respond to questions can be a successful strategy. In addition, if an individual covers their ears or runs from the first responder toward danger, such as a busy road, it is likely that they are sensitive to sounds. Removing loud sounds can be an effective means to successfully guiding the individual towards safety. Deficits in communication are a core symptom of ASD (DSM-5), so using simple concrete language with gestures such as pointing toward the direction they need to move may improve the individual’s ability to follow directions during an emergency. Avoiding touching the individual, unless critically necessary, may prevent the individual from moving away from the first responder.

Be Prepared to Work with First Responders

One of the best things a parent can do to improve the effectiveness of first responders’ interactions during an emergency is to be prepared to work with them. That starts with having an emergency kit on hand with the following items:

- Current photo of your child daily on phone to show what they are wearing

- Current description (height, weight, hair color, etc.)

- Special needs

- Mode of communication

- Medications and allergies

- Family contact information

Elopement is one of the most common reasons a child with ASD might encounter a first responder. More than 50% of children with ASD have a history of elopement.11 Once away from their caregivers, children with ASD can face a significant risk of harm. Drowning and traffic accidents are two of the top concerns.12 To assist first responders, consider having a map of the area that identifies any of the child’s favorite places that they might seek out, as well as nearby bodies of water like pools, ponds, creeks, lakes, and rivers. Depending on the child, consider using a tracking device to maintain awareness of their whereabouts. Autism Speaks maintains a comprehensive list of safety products and tracking services, many of which integrate with first responder organizations. Links to these resources can be found below.

Sometimes an encounter with a first responder takes place when a caregiver is not available. Examples of when a caregiver may not be present are when an adult with ASD is pulled over for a traffic stop, or a caregiver is incapacitated when emergency services show up at the home. Situations like these can be extremely stressful and sometimes completely unmanageable for an autistic person. To mitigate the severity of these situations, there are a few practical steps caregivers can take. In addition to registering the child with local emergency services, some of the following measures should be considered:

- Print out a medical card that adults with ASD can carry in their wallet and show to emergency personnel when needed.

- Place a sticker on the front door of the home that identifies a child with autism lives there.

- Have the individual wear a medical bracelet that first responders can use to identify individuals with ASD.

In conclusion, much needs to be improved upon to ensure the safety of individuals with ASD in their community. Assisting in this endeavor is to educate first responders in steps they can take to understand this vulnerable population and to interact with them in a manner that is safe and successful. Following the suggestions outlined above is a way to work toward that outcome.

Resources

- National Autism Association First

Responder Toolkit - Autism Speaks Autism Safety Project

- Autism Speaks Information for First Responders

- Autism Speaks Safety Products and Services

Thea Davis, MSEd, BCBA, is Founder and Executive Director at Autism Bridges and Andrea Lavigne, PhD, BCBA, is Vice President at Autism Care Partners.

Footnotes

- Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Aug;168(8):721-8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210. PMID: 24911948

- What is Autism Spectrum Disorder? (2020, March 25). Retrieved from cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html

- Guan, J., & Guohua Li. (2017). Injury Mortality in Individuals with Autism. American Journal of Public Health, 107(5), 791–793. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303696

- Lunsky Y, Paquette-Smith M, Weiss JA, Lee J. Predictors of emergency service use in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder living with family. Emerg Med J. 2015 Oct;32(10):787-92. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204015. Epub 2014 Nov 28. PMID: 25433045.

- Rava, J., Shattuck, P., Rast, J., & Roux, A. (2017). The prevalence and correlates of involvement in the criminal justice system among youth on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 340–346

- Railey, K. S., Bowers-Campbell, J., Love, A. M. A., & Campbell, J. M. (2020). An Exploration of Law Enforcement Officers’ Training Needs and Interactions with Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 50(1), 101–117. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1007/s10803-019-04227-2

- Gardner L, Campbell JM, Westdal J. Brief Report: Descriptive Analysis of Law Enforcement Officers’ Experiences with and Knowledge of Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019 Mar;49(3):1278-1283. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3794-4. PMID: 30357646.

- Hinkle, K. A., & Lerman, D. C. (2021). Preparing Law Enforcement Officers to Engage Successfully with Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Evaluation of a Performance-Based Approach. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1007/s10803-021-05192-5

- Hollow, M. C. (2020, February 27). When the Police Stop a Teenager With Special Needs. Retrieved from nytimes.com/2020/02/27/well/family/autism-special-needs-police.html

- Copenhaver, A., & Tewksbury, R. (2019). Interactions Between Autistic Individuals and Law Enforcement: a Mixed-Methods Exploratory Study. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 44, 309-333.

- Scheithauer, M., Call, N.A., Lomas Mevers, J. et al. A Feasibility Randomized Clinical Trial of a Structured Function-Based Intervention for Elopement in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 51, 2866–2875 (2021). https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1007/s10803-020-04753-4

- Anderson, C., Law, J. K., Daniels, A., Rice, C., Mandell, D. S., Hagopian, L., & Law, P. A. (2012). Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 130(5), 870–877. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1542/peds.2012-0762