Supporting families and caregivers is a lifelong learning process as children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) typically undergo many changes. When providing workshops to families about accessing services, I began to consider the question of how we can support them further, as simply providing information does not seem to be enough.

A Chance to Be Heard

Parents and caregivers must be given the opportunity to be heard so educators and practitioners can better understand their children’s lives, goals, and dreams. The impact of a child’s developmental disability or other mental health issues can truly impact parents’, caregivers’, and family functioning (Prendeville & Kinsella, 2019). Family functioning plays an important role in understanding parental interactions with children diagnosed with developmental disabilities. Understanding their interactions may help educators and practitioners develop an approach, or needed interventions, to enhance their day-to-day functioning at home and determine future valued outcomes (Prendeville & Kinsella, 2019). Parents and caregivers often struggle to obtain access to health, social and financial support (Doherty et al., 2020). Their socioeconomic status may pose limitations in advocating for their children due to their work schedules, financial resources, and lack of access to information about their children’s rights and entitlements (Doherty et al., 2020). Such factors can affect their family functioning and their child’s transition to adult life.

Focusing on the Person in Future Planning

Generally, students transitioning from school to adulthood can pose challenges. For students with ASD, the process can be overwhelming, while families and caregivers often face systemic barriers in accessing adult day services, benefits, and entitlements upon transitioning from educational services (McGinley et al., 2021). Such barriers include a lack of knowledge about several transition tasks which may affect students’ access to community inclusion and the workforce. Person-centered planning emerges as an approach for future planning. This allows parents, educators, practitioners, and service providers to assess, explore, determine, and implement valued outcomes for their children who require support. Such an approach has promoted ongoing support to parents and caregivers of children with ASD and other developmental disabilities.

Collaboration Leads to New Vision

Person-centered planning refers to the process of articulating the care and support needs of individuals with developmental disabilities in a manner of pursuing and achieving their goals that is collaborative (Heller, 2019). It is rooted in the social values of equality and access to the community for individuals with developmental disabilities whereby decisions are based upon the principles of inclusion, choice, and independence (Taylor & Taylor, 2017). This approach aims to place children and young adults at the center of planning and decisions that affect them. When they are actively involved in person-centered planning, it is believed that their attitudes, behavior, and learning contribute positively to the community. When and how do parents and caregivers decide about the future for their children and young adults?

Seeing Children Through a Different Lens

When engaging in person-centered planning with parents and caregivers, it is important to explore their children’s profiles in terms of who they are, their aspirations and dreams, prior to determining future valued outcomes. Self-awareness is key to goal setting in person-centered planning. As parents and caregivers reflect on their children’s capabilities, they begin identifying what is important to their child and the supports he or she will require to contribute to society. During such exploration, parents, caregivers, and practitioners see their children through a different lens.

A parent once told me during a person-centered planning meeting, “I have never thought of seeing my son from a different perspective; I tended to focus so much on his deficits in certain areas of his life. This meeting opened my eyes to see his potential in other areas and other possibilities, such as attending college.”

As parents and caregivers interact in a natural way, there is a strong sense of engagement and inner reflection of themselves. Their conversations may lead to setting valued outcomes for their children that might seem unrealistic to others or goals that could be attainable.

The goal-setting process is rooted in transforming their children’s dreams into goals and objectives. Goals and objectives based on their children’s wants and needs and supported by parents, caregivers, and service providers, can lead to set activities and a timeline that allows their children to accomplish them effectively. In a transition meeting, a student completed a picture of his life through person-centered planning by including both graphic and written descriptions of his preferred place to live, work and other dreams he wanted to accomplish. Parents and caregivers were able to picture and reflect upon his vision from a different perspective: his own perspective.

Person-centered planning has indeed evolved toward an empathic approach that empowers and motivates children and young adults with developmental disabilities, as well as their parents and/or caregivers. With the opportunity to articulate a vision, parents and caregivers consider different paths, and engage in natural conversations centered on their children. Over time, this approach has improved the relationship between parents/caregivers and their children, while promoting respect and dignity, which forges a deeper emotional bond.

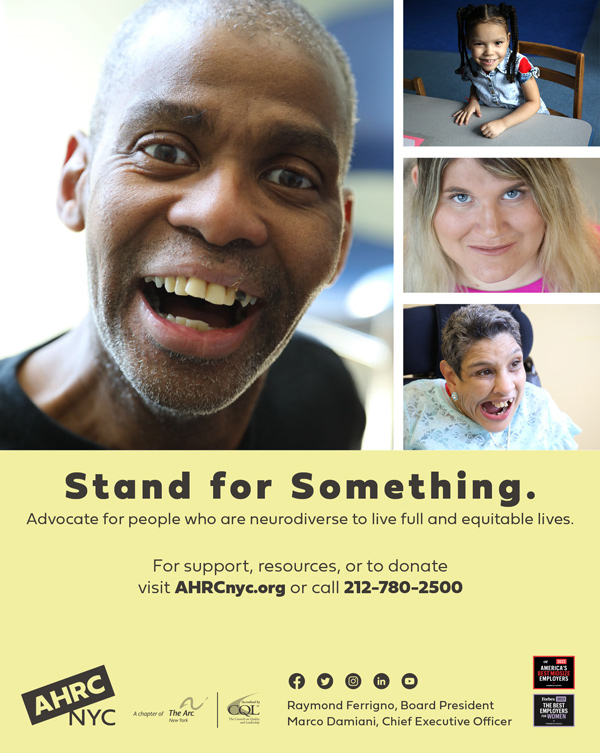

Trudy Ann Pines, MSEd is an Assistant Principal at AHRC NYC Middle/High School in Brooklyn and serves as a Care Manager for Care Design New York. She also was a school counselor at AHRC NYC Middle/High School for 14 years. She earned her master’s degree in School Counseling and Educational Leadership at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York and is currently completing her doctoral degree at St. Thomas University. Her research interest includes social and emotional learning in special education and transition services for students with developmental disabilities post-COVID-19 pandemic. Trudy Ann resides with her family in Brooklyn. In her free time, she runs outdoors, practices journal writing, and spends quality time with her daughter.

References

Doherty, M., Lynden, B., Lauren, J., Julie, T., & Stanhope, V. (2020). Transitioning to person-centered: A qualitative study of provider perspectives. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 47(3), 399-408.

Heller, T. (2019). Bridging and aging an intellectual/developmental disability in research, policy, and practice. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 53-57.

McGinley, J., Marsack-Topolewski, C., Church, H. L., & Knoke, V. (2021). Advance care planning for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A state-by-state content analysis of person-centered service plans. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 59(4), 352-364.

Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2019). The role of grandparents in supporting families of children with autism spectrum disorders: A family systems approach. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 738-749.

Taylor, J.E., & Taylor, J.A. (2017). Person-centered planning: Evidence-based practice, challenges, and potential for the 21st century. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 12(3), 213-235.