Adolescence is a developmental period that brings challenges to all children and parents. More extensive challenges can be experienced by children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and their families. Understanding and coping with the physical, social, and emotional changes of adolescence is difficult for young teens. The socialization, communication, and learning challenges associated with ASD contribute to the greater challenges faced by these teens. Individuals with ASD often take longer to adjust to and understand changes in their lives than typically developing teens. High quality sexuality education is essential in preparing adolescents for the physical and social changes they’ll be experiencing. For students with ASD, sexuality education material generally needs to be adapted to effectively provide for acquisition of essential knowledge and skills. Important areas of sexuality education focus include personal boundaries and space, understanding the difference between public and private, prevention of sexual abuse, and personal hygiene skills.

One area that has not received sufficient attention in the literature is skill instruction for menstrual care. The ability to independently manage menstrual care provides women with disabilities greater privacy and more extensive life options. At AHRC New York City schools, a multifaceted approach to menstrual care instruction, addressing both knowledge and skill acquisition, has been found to be most effective.

Social Stories

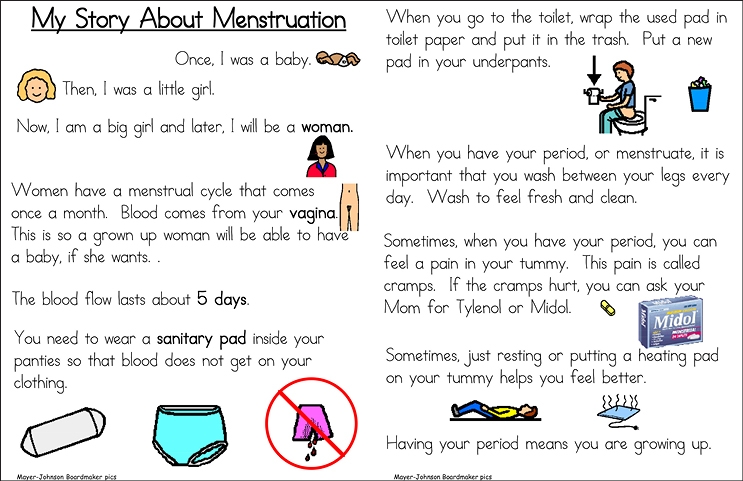

Knowledge of menstrual care should include an understanding of what menstrual flow will look like, that the flow is normal for girls, that it will happen for five or six days each month, and that special hygiene skills must be performed. We have found the use of Social Stories to be very effective for students unable to understand this information through traditional instruction.

Lisa Barzotto, MS, BCBA, LBA

Mary Donahue, PhD, BCBA-D, LBA

Social Stories is an instructional approach using easily understood information to provide students with ASD an understanding of events, behaviors, and social rules for a wide range of situations. Ballen and Freyer (2017) describe Social Stories as explaining “a situation, concept, or social skill from the perspective and comprehension level of a child with ASD” (p266). Through the use of short text and relevant cues, the expected behaviors for a given situation are provided. Social Stories typically consist of five to ten sentences, utilizing certain sentence types. They generally consist of two to five descriptive sentences related to the situation, one directive sentence explaining appropriate behavioral response to the situation, one perspective sentence depicting the feelings and response of others, and one control sentence depicting how and when one would use the learned strategies and skills. Social Stories effectively answer the relevant “wh” questions for the situation, such as when, where, and why the skill will be needed. In addition to text, pictures are often included in the Social Story to add additional cues or clarification.

Social stories have been demonstrated to be an effective strategy for menstrual care instruction for girls with ASD. Klett & Turan (2012) effectively taught girls to independently complete an 11-step bathroom routine for changing a sanitary pad through the use of Social Stories and an instructional task analysis. They used three Social Stories with the girls, “Growing Up,” “My Period,” and “How to Take Care of My Period” along with skill instruction using the task analysis.

AHRC NYC schools have used Social Stories to address a variety of issues related to emerging sexuality, including boundaries, privacy, relationships, and menstrual care. Specific to menstrual care, Social Stories have been implemented that address general information about menstruation, and specific behaviors related to changing a menstrual pad and related personal hygiene tasks. Social Stories are individually developed for each learner. In addition to considering the receptive language level and reading ability of the student, it’s important to consider any variations in language used by the family for specific terms, such as “period” or “time of month,” etc. Consideration also needs to be given to various skill expectations for the home setting, such as where soiled underwear should be placed, or how to dispose of the pad. Based upon the learner’s ability, there will need to be variation in the type and extent of visual material included in the Social Story. Incorporating pictures is often helpful in facilitating understanding of concepts and related feelings. When more extensive information is needed, it is often best to write separate Social Stories for different aspects of the situation, rather than making one long story. For example, a separate Social Story might address coping with PMS. Teens with ASD will experience the same symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) as typically developing teens; however, teens with ASD may find it more difficult to communicate or regulate the emotions that might accompany PMS. A Social Story might describe how she might be feeling (e.g., irritable, trouble concentrating, sore stomach, sleepy, etc.).

A significant advantage of Social Stories is that they allow for repeated review of the same information without variation. A copy can be sent home so parents can also review the Social Story, especially in context of personal hygiene care.

ABA-Based Instructional Strategies

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) uses evidence-based strategies to systematically teach new behaviors. Task Analysis and Chaining are common ABA instructional approaches. Task Analysis involves breaking a task down into sequential component steps that can be targeted for instruction. Chaining involves sequentially teaching these steps through use of prompts and differential reinforcement. Menstrual care skills have been effectively taught using these approaches in a number of studies (Ersoy, Tekin-Iftar, Kircaali-Iftar, 2009 and; Veazey, Valentino, Low, McElory, LeBlanc, 2016).

At AHRC NYC schools, instruction using task analysis and chaining has been provided both using dolls and in vivo training with the student. Instruction using dolls can include a simulation of a soiled pad with food coloring. Task analysis steps include removing and properly disposing of the soiled pad, replacing it with a clean one, and following proper hand washing procedures. Similar strategies can be provided during in vivo training depending upon the support needs of the student. Repeated instruction on specific task analysis steps is provided using modeling, a prompt hierarchy, and response feedback, including error correction or reinforcement. Video modeling can also be considered as a potential option for instruction. Consideration needs to be given as to whether instruction will only take place during menstruation, or also will be provided at other times. Providing more frequent instruction facilitates faster learning, but may cause confusion for some students as to when the skills need to be performed.

Some students may require ongoing additional supports to achieve greater independence. Visual strips of the required steps can be provided to serve as a visual prompt, thereby removing the need for adult-delivered prompts. Adding visual structure by color coding the bottom of the pad and the center of the underwear to show pad location also has been helpful. A visual schedule can be used to cue the student on when and how often the pad should be changed. Where possible, pad change times should fit into the normal break schedule of the student’s day. Adding technology in the form of a vibrating watch can be another helpful approach for cuing students to change the pad at set times. To encourage independence and self-management of menstrual care, the student can be taught how to use a calendar and/or an app to plan when her period is due.

Effective instruction needs to plan for generalization of the skills involved in menstrual care. Once basic steps are mastered, instruction should plan for variations across material and settings. An example of variation in material would be use of different types of pads, such as those with and without wings, light flow pads, etc. Variation in setting would include skills needed to dispose of the soiled pad in public restrooms, as well as in school and at home.

Desensitization

One aspect of menstrual care not addressed by research is the refusal of some girls to wear sanitary pads due to sensory sensitivities. In such cases, a desensitization approach can be effective in order to gradually expose the student to wearing the pad. Having the student wear increasingly larger or thicker sections of pads over a period of time can increase tolerance to the sensation of the pad. Begin with a very small, thin section of the pad and gradually increase size and thickness as the student’s tolerance improves.

In summary, preparing girls for independent menstrual care requires that they achieve both knowledge and skill acquisition. Menstrual care requires new skills in a private body area, thus requiring enhanced planning and sensitivity for instruction. The generally accepted practice is to begin this preparation prior to the onset of menstruation. The timing of instruction onset can be a joint decision between parents and professionals, with parents giving guidance based upon signs of physical maturation. For a small minority of students, it may be felt that providing early instruction may heighten anxiety and the tendency to fixate. In such cases, instruction may be delayed until the onset of menstruation. While greater research is needed on the topic, current evidence and experience supports the use of multifaceted, evidence-based approaches. AHRC NYC schools have found the use of Social Stories, ABA instructional strategies and desensitization programs to be effective in helping students to increase menstrual care knowledge and skills.

Mary Donahue is the Vice President for Behavior Support Strategies for AHRC New York City. She is a licensed psychologist and licensed behavior analyst, specializing in providing evidence-based interventions for children and adults with challenging behavior. Mary is a professor in the School of Education at St. John’s University.

Lisa Barzotto is a certified school psychologist and board-certified behavior analyst (BCBA) who works for the New York City Department of Education. Previously, she worked for 10 years as the school psychologist of AHRC New York City’s Brooklyn Blue Feather Elementary School. Lisa’s interests include behavioral interventions in Autism Spectrum Disorders (early identification and intervention, parent and teacher training, coping strategies for managing anxiety, and social skills interventions) as well as dissemination of ‘best practices’ in ASD interventions in schools and the community.

For more information, visit www.ahrcnyc.org.

References

Ballan, M., & Freyer, M. (2017). Autism Spectrum Disorder, Adolescence, and Sexuality Education: Suggested Interventions for Mental Health Professionals. Sexuality and Disability, 35, 261-273.

Esroy, G., Tekin-Iftar, E., & Kircaali-Iftar, G. (2009). Effects of Antecedent Prompt and Test Procedure on Teaching Simulated Menstrual Care Skills to Females with Developmental Disabilities. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 44, 54-66.

Klett, L., & Turan, Y. (2012). Generalized Effects of Social Stories with Task Analysis for Teaching Menstrual Care to Three Young Girls with Autism. Sexuality and Disability, 30, 319-336.

Veazey, S., Valentino, A., Low, A., McElroy, A., & LeBlanc, L. (2016). Teaching Feminine Hygiene Skills to Young Females with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability. Behavior Analysis Practice, 9, 184-189.