There has been an increase in the prevalence of childhood disability worldwide. One in six children, ages 3-17, has recently been diagnosed with a developmental disability.1 Parenting children with a disability poses challenges for all parents, although immigrant parents experience more difficulties in caring for their children with disabilities related to adaptation, finance, accessing services, and stigma.2 Some of the challenges immigrant parents face in raising children with a disability include adapting to the new country’s culture, norms, customs, and the language barrier, which is the most common barrier in schools, and the lack of information on resources available to immigrant parents and their child with a disability.3

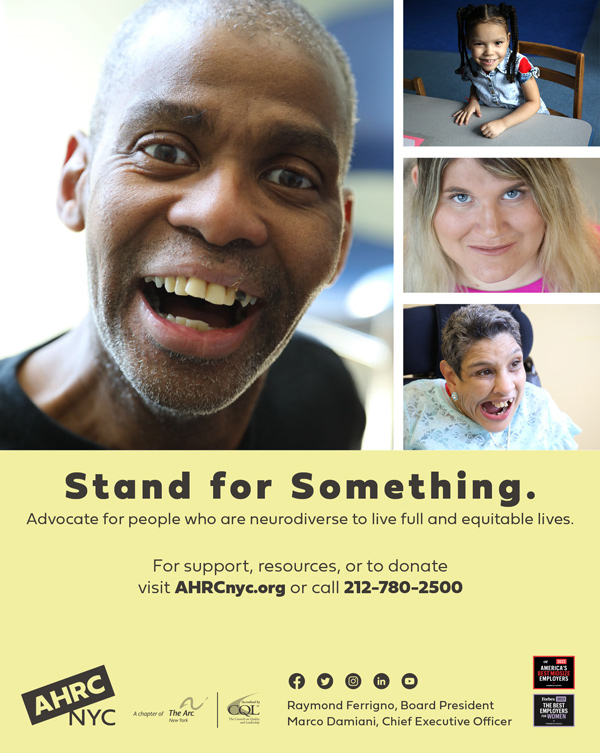

More than half of the students identified with a disability in AHRC New York City’s schools are from culturally diverse backgrounds, with some new immigrants and other new families who have been in this country for many years. Immigrant families who have been in the U.S. for many years were born and raised in Latin and Central American countries such as Ecuador, Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. Limited English language proficiency is a significant factor that may inhibit immigrant parents from taking part in their children’s education and access to services. Additionally, some school staff are not as open to diverse cultures as they might be, therefore complicating matters further. Immigrant parents with limited English language proficiency may not feel confident communicating with the school staff about their concerns related to their children’s cognitive and social-emotional deficits due to the nature of the disability. Furthermore, immigrant parents may not understand their children’s special education needs and parents’ rights to ensure their children receive appropriate education. Therefore, schools must prioritize engaging their families best throughout their transition from school to adulthood.

Family Engagement Process

When engaging with immigrant parents of a child with a disability, they have reported not receiving the information and resources available to help their children’s academic, social, and emotional needs to succeed in school.4 In my experience as an educator, I have a primary role in the families’ engagement process. I recall helping an immigrant family whose older child, diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, was struggling to adjust to the classroom routine upon returning to school from the 2020 COVID-19 shutdown. The parents could not understand why their child was having such behavioral challenges, and they expressed feeling embarrassed to seek help on behalf of their child. After several meetings and conversations with the parents, I realized that parents’ beliefs about the nature of their child’s disability may have impeded access to the information and resources available.5 A parent reported in conversation, “In our culture, we do not discuss our home issues with professionals; we believe we must solve our home issues to the best of our ability, but our child’s behavior at home and in the school community has been so difficult to manage, and we concluded that we truly need help, but we do not know how to seek help.”

Parents are encouraged to be exposed to essential roles they can play for their child, take action, and ensure behavioral supports are in place.6 At the same time, I have to be sensitive to the family’s situation and be realistic about the family’s role in their child’s behavioral treatment by building a collaborative relationship and respecting the family’s cultural beliefs and priorities.

Parent Counseling and Training

Parent counseling and training in schools is not only essential to help immigrant families of children with special needs, but it also is considered the most effective intervention for these students.7 Discussion and empirical evidence related to the importance of family involvement in intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder dates back to the early 1970s.8 According to research, parents have potentially more significant impacts on their children’s outcomes.9 Parent counseling and training consists of educators helping parents understand their child’s educational needs, providing parents with information about their child’s development, parent support groups, social services, financial assistance resources, and other sources of information and support outside the school system. Immigrant families benefit from parent counseling and training as they will gain a better understanding of their child’s disability, will be better informed to be equal team members, and will be active participants in the implementation of their child’s IEP.10 One strategy I have found effective in providing parent counseling and training for immigrant families is to match the families with educators or trainers who speak the same language. I was able to offer transition services workshops in their native language to inform and facilitate access to services their child was entitled to receive. For example, the parents were informed in their native language of the benefits of obtaining New York State OPWDD (Office for People with Developmental Disabilities) eligibility, waiver, and care management services. Parents were encouraged and guided to participate in webinars in their native language to learn how to become eligible for services and receive care management support.

Parents expressed satisfaction in receiving such vital information as it would help support their child’s social and behavioral needs. Parents were further assisted by submitting referrals on their behalf to agencies for required evaluations to determine eligibility for services. Knowledge of the law, their child’s rights, parental rights, and the services their child was entitled to was crucial in deciding the best behavioral support for their child. The parents were given the Spanish version of A Parent’s Guide to Special Education Services for School-Age Children, which is a map that lays out information on special education instruction, supports, and services that children with disabilities need to succeed during their school transition years. Information on agencies that provide behavioral services was provided through transition workshops via Zoom in their primary language. Thus, incorporating technology in transition workshops was a practical solution to overcome the family’s language barrier.

Keeping immigrant families of children with disabilities informed is one way of supporting and empowering them to engage in their children’s educational journey from school to adulthood. However, engaging immigrant parents of children with disabilities continues to require ongoing new and innovative solutions to provide sufficient time to spend with them; offer two-way communication so their children’s specific needs are being met and services are being informed efficiently, and offer high-quality language interpretation and translation in their first language. Such innovative solutions include in-person conversations, written handouts, emails, video-streaming events, and partnerships with local community groups.11 Most importantly, following up with immigrant families increases family engagement in schools, contributing to positive student outcomes. Immigrant parents of children with disabilities have their rights, and it is crucial to help them create opportunities to develop relationships and family leadership in the school community.

Trudy Ann Pines, EdD, is an Assistant Principal at AHRC NYC Middle/High School in Brooklyn and serves as a Care Manager for Care Design New York. She also was a School Counselor at AHRC NYC Middle/High School for 14 years. She earned her Doctoral degree in Educational Leadership and Innovation-Administration at St. Thomas University, Miami Gardens, Florida. Her research interest includes school transition services for students with developmental disabilities post-COVID-19 pandemic. Trudy Ann lives with her family in Brooklyn. In her free time, she runs outdoors, practices journal writing and spends quality time with her daughter.

Footnotes

1,5 Arfa, S., Per, K. S., Berg, B., & Jahnsen, R. (2020). Disabled and immigrant, a double minority challenge: A qualitative study about the experiences of immigrant parents of children with disabilities navigating health and rehabilitation services in Norway. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 1-16.

2 Alsharaydeh, E. A., Alqudah, M., Lee, R., Lai T., & Chan, S.W. (2019). Challenges, coping, and resilience among immigrant parents caring for a child with a disability: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 51(6), 670-679.

3, 4, 6, 11 Brassart, E., Prévost, C., Bétrisey, C., Lemieux, M., & Desmarais, C. (2017). Strategies developed by service providers to enhance treatment engagement by immigrant parents raising a child with a disability. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(4), 1230-1244.

7, 10 Lim, N., O’Reilly Mark, Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. E., & Sanchez Neyda, J. (2021). A review of barriers experienced by immigrant parents of children with autism when accessing services. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 8(3), 366-372.

8 Lovaas, O.I., Koegel, R.L., Simmons, J.Q. & Long, J.S. (1973). Some generalization and follow-up measures on autistic children in behavior therapy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 6, 131-165.

8 Schopler, E., Brehnm, S., Kinsbourne, M., & Reichler, R.J. (1971). Effect of treatment structure on development in autistic children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24, 415-421.

9 Jang, J., Dixon, D.R., Tabox, J., Granpeesheh, D., & Kornack, J. (2012). Randomized trial of an eLearning program for training family members of children with autism in the principles and procedures of applied behavior analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 852-856.