Across the next decade, we can expect a 123% increase in the number of youth with autism transitioning out of school-based services (IACC, 2017). These increases have placed a growing demand on the service systems supporting transition-aged youth and adults and magnified the need for effective and evidence-based programs for adults with autism. The Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) has identified service access for adults with autism as a priority, including understanding service gaps and barriers. The IACC Strategic Plan for autism indicates many of the challenges faced in working with adults with autism are related to the lack of a well-trained and motivated workforce (IACC, 2017). Insufficient use of evidence-based practices (EBPs) is linked to poor pre-service training, supervision in the field, and a sense that the use of EBPs is not expected, supported, and rewarded (IACC, 2017). There is a clear need for the development of appropriate interventions for adults with autism and effective training practices for their support providers.

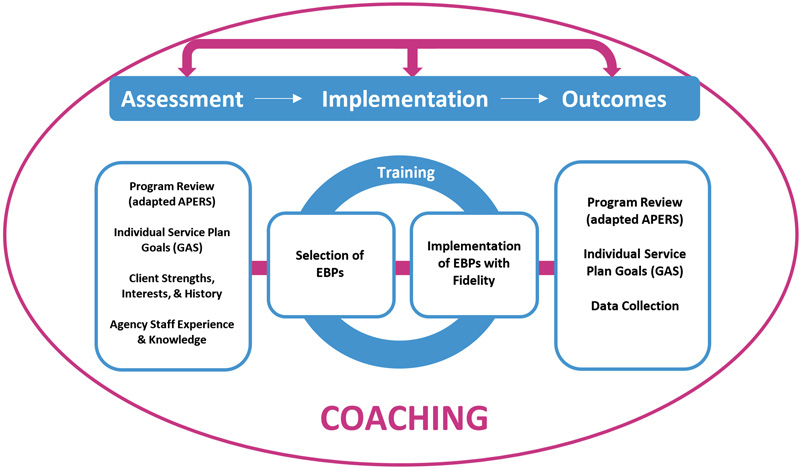

Figure 1. Adaptation to the National Professional Development Center for ASD

The National Professional Development Center for ASD (NPDC-ASD) developed a professional development model to support states in increasing the use of EBPs for autism in public school programs (Cox et al., 2013). The model involves systematic program assessment (Odom et al., 2018), structured evaluation of student progress toward annual goals (Ruble et al., 2012), and provider training on the implementation of EBPs. The model and resources are associated with increases in overall program quality, use, and fidelity of EBPs and individual student progress (Odom et al., 2013). Resources include the Autism Focused Intervention Resources & Modules (AFIRM), which present the 28 EBPs identified by the NPDC-ASD into interactive online modules with specific steps for teachers and practitioners to plan for, use, and monitor each practice (afirm.fpg.unc.edu).

One organization that has employed the NPDC-ASD model and resources is the California Autism Professional Training and Information Network (CAPTAIN; Suhrheinrich et al., 2020). As part of a CAPTAIN initiative to scale out the use of EBPs, CAPTAIN piloted an adaptation of the NPDC-ASD resources and training model into adult day programs. Participating adult clients with autism met or exceeded their goals, had a reduced need for individual behavior intervention plans, and had greater access to the program curriculum (Rettinhouse, 2018).

Given the positive outcomes of this pilot program, grant funding was secured to adapt additional resources, expand the training capacity, and evaluate the effectiveness of the adapted model. The current study included three specific aims:

Aim 1: Evaluate staff and organizational characteristics and needs. Which EBPs do staff and administrators at community care facilities report as helpful in meeting the needs of adults with autism?

Aim 2: Adapt NPDC-ASD training resources to support direct service provider (DSP) knowledge and use of EBPs for autism. How can training resources be selected and adapted to fit the needs of staff working with adults in community care facilities?

Aim 3: Assess the effectiveness of the adapted model and resources in three developmental disability service agencies supporting adults with autism. How effective is the training program in increasing staff knowledge of EBPs? How did staff and agency participation impact progress on client goals?

Aim 1: Evaluate Staff and Organizational Needs

A survey was distributed to community care facility administrators, DSPs, and parents and caregivers of adults with autism and intellectual disabilities. A total of 88 individuals completed the online survey, including 13 DSPs, 73 facility administrators, and 2 parents. We asked about the top areas of need of adults with autism living in group homes. Behavior was reported as the top need (n=52, 22.4%), followed by adaptive skills (n=43, 18.5%), mental health (n=36, 15.52%), and social skills (n=31, 13.4%). We also asked about the EBPs that would be most helpful in targeting these areas of need. Antecedent-Based Interventions were the top EBP reported (n=26, 19.7%), followed by Functional Behavior Assessment (n=17, 12.9%), Reinforcement and Differential Reinforcement (n=15, 11.4%), and Prompting (n=8, 9.1%).

Site assessments for ten local area care facilities were completed to evaluate which EBPs were currently in use. During site assessments, evidence-based teaching practices were not being used to address existing goals across nine out of 10 facilities, and support was largely provided in a “do-for” manner, meaning that direct support professionals would complete activities of daily living for the clients residing in their care rather than supporting them to complete activities independently.

Aim 2: Adapt NPDC-ASD Training Resources

Two EBPs were selected based on data gathered from the survey and site assessments, as well as the level of technical skill required of providers and the utility of the practices, such as Prompting and Visual Supports. The modules for these two EBPs were adapted to include content relevant to staff working with adults. For example, video content for the Prompting module includes both adult actors and scenarios relevant to adult clients. Modules include video clips of professionals explaining how they have used both visual supports and prompting strategies in ways that are most effective with older learners. Both modules are hosted on an interactive platform (PlayPosit) that allows users to view the video presentation and digitally complete activities and content questions. Participants received feedback in response to content questions to support enhanced learning, and pre/post-tests were embedded into each presentation to assess trainee knowledge gain.

Aim 3: Assess the Effectiveness of the Adapted Model and Resources

We implemented the adapted resources and training program in three community care facilities. Seven staff and one parent participated in the training activities and seven clients agreed to participate in the project. The training program consisted of an initial half-day interactive didactic training workshop. Together with the staff and administrator, the trainer helped to develop relevant and appropriate goals for each participating client, considering their strengths, interests, and history. Each facility received a start-up kit of materials to prepare Visual Supports related to the individualized client goals. Additionally, staff participated in weekly virtual coaching sessions with the trainer to discuss progress toward the goal and the implementation of EBPs. The total length of the training program was five weeks, with a follow-up interview with each community care facility administrator.

Prior to training, providers were asked about their confidence using Visual Supports and Prompting. A majority of participants rated their confidence using both Visual Supports and Prompting in the low-moderate range. Providers also completed a pre-post knowledge assessment for each EBP. Post-test results indicate increases in knowledge for both EBPs, with an average score of 65% (35% at pre-test) for Prompting and 76% (65% at pre-test) for Visual Supports across all participants. The trainer report indicated a high level of engagement during training for all participants.

Each community care facility was assessed for overall quality, including site structure, organization, and use of visual supports. Results indicate notable improvement for all sites. Post-intervention, administrators reported finding Visual Supports, Prompting, and the training program to be accessible, fitting, easy to use, and applicable to their setting.

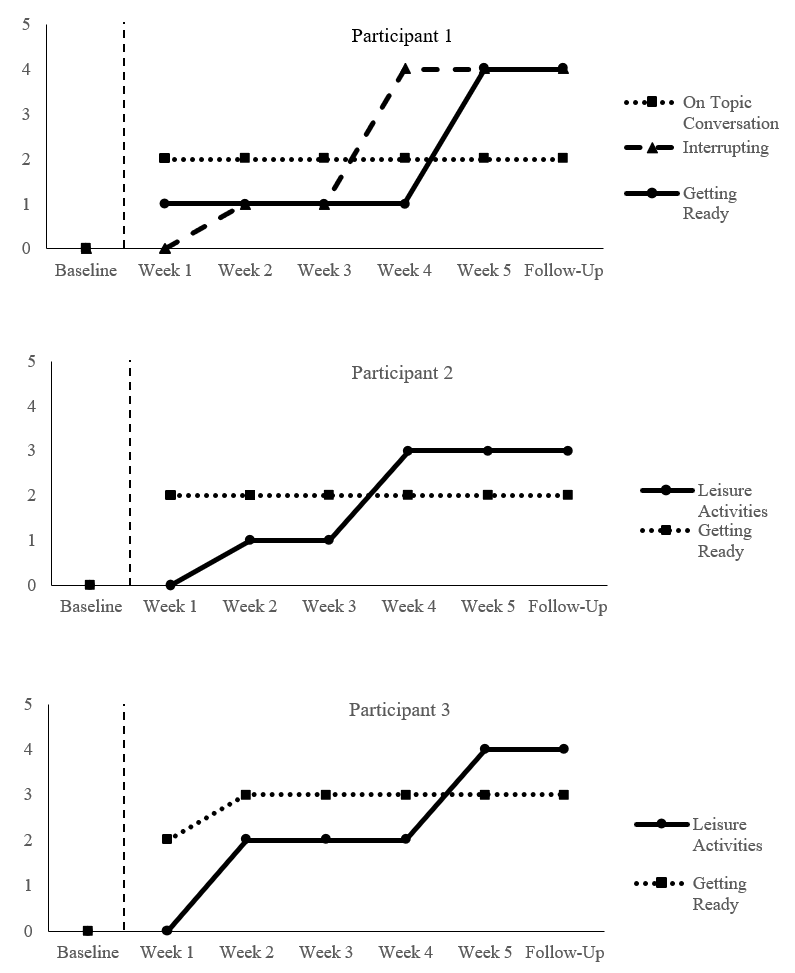

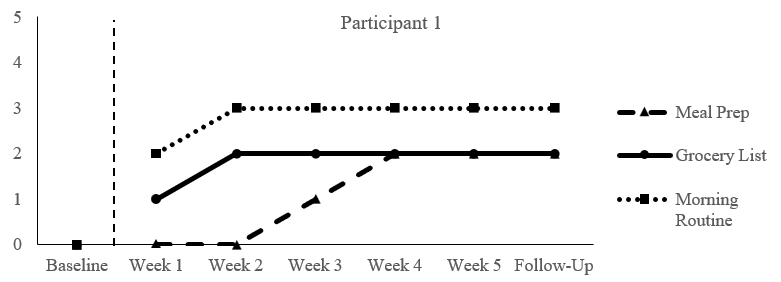

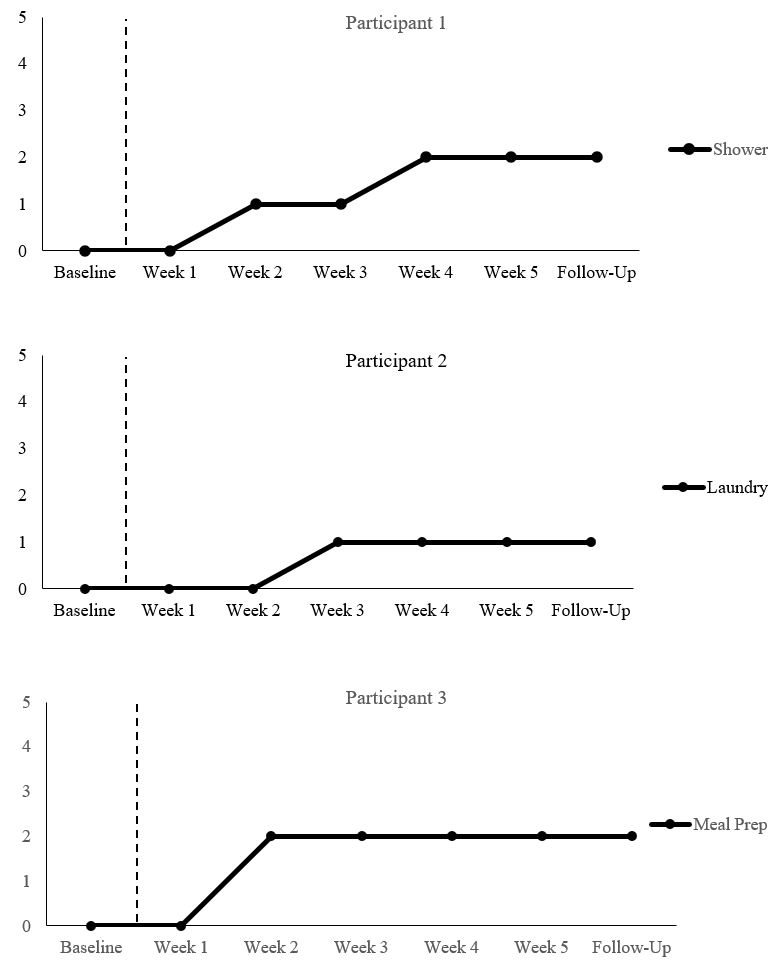

At the client level, goal progress was monitored using Goal Attainment Scaling (0 = original level of performance, 1 = less than expected progress, 2 = expected level of progress, 3 = somewhat more than expected, and 4 = much more than expected; Ruble et al., 2012). The majority of client goals targeted self-help/adaptive skills (66.7%), such as preparing meals, laundry, morning routines, and showering. Social skills (16.7%), such as staying on topic and engaging in leisure activities (16.7%), were also targeted. By the end of the training program, all clients but one had reached their expected level of progress, and almost half (46.1%) had exceeded their expected level of progress.

Figure 2. Changes in Goal Progression for Participants at Site 1

Figure 3. Changes in Goal Progression for Participant at Site 2

Figure 4. Changes in Goal Progression for Participants at Site 3

Discussion

Our results show that a short-term intensive training program can produce positive outcomes at the staff and client levels. Staff also felt more comfortable and competent in implementing evidence-based practices, as indicated by our pre- and post-training surveys. Since increases in self-efficacy have been shown within other service systems (Yost, 2006) to increase staff retention, this type of training program could have significant implications on workforce retention in a field that is plagued by staff shortages and high turnover rates. The majority of adult client participants improved their self-help/adaptive and social skills. These skills will improve their quality of life by increasing their independence as well as their ability to engage in the community. Our findings are promising, and ongoing funding would allow the intervention to be implemented across a larger sample as well as replicated in other types of agencies like day programs, vocational programs, and family homes.

An additional goal related to the development of these tailored resources specifically for adults within community-based services was to increase the interest in EBPs by community service agencies and by those funding them. The resources developed for this project are publicly available through the CAPTAIN website (www.captain.ca.gov). We have additional plans to disseminate our findings to stakeholders throughout the state, including the agencies who fund adult services as well as parents, self-advocates, and those who can assist with advocating for high-quality, evidence-based care for this population.

Melina Melgarejo, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Departments of Special Education and Dual Language & English Learner Education at San Diego State University and can be reached at mmelgarejo@sdsu.edu. Jessica Suhrheinrich, PhD is Associate Professor in the Department of Special Education at San Diego State University. Mary Rettinhouse, MS, BCaBA, is Autism Clinical Specialist at Alta California Regional Center. Patricia Schetter, MA, BCBA, is Program Coordinator at Placer County Office of Education. Tana Holt, BS, is Research Assistant at San Diego State University.

References

Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules Team. (2018). Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules. Chapel Hill, NC: National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder, FPG Child Development Center, University of North Carolina. afirm.fpg.unc.edu/.

California Autism Professional Training and Information Network. (2017). Welcome. www.captain.ca.gov/

Cox, A., Brock, M. E., Odom, S. L., Rogers, S. J., Sullivan, L. H., Tuchman-Ginsberg, L., Franzone, E. L., Szidon, K., & Collet-Klingenberg, L. (2013). National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders: An emerging national educational strategy. In P. Doehring (Ed.), Autism services across America: Road maps for improving state and national education, research, and training programs (pp. 249-266). Brookes.

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC). 2016-2017 Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee Strategic Plan for Autism Spectrum Disorder. October 2017. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee website: iacc.hhs.gov/publications/strategic-plan/2017/

Odom, S. L., Cox, A. W., & Brock, M. E. (2013). Implementation science, professional development, and autism spectrum disorders. Exceptional Children, 79(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291307900207

Odom, S. L., Cox, A., Sideris, J., Hume, K. A., Hedges, S., Kucharczyk, S., Shaw, E., Boyd, B. A., Reszka, S., & Neitzel, J. (2018). Assessing quality of program environments for children and youth with autism: Autism Program Environment Rating Scale. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 913–924. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29159578/

Rettinhouse, M. (2018). Replicating the NPDC model in an adult day program: A report on sustainability. CAPTAIN Annual Summit, Sacramento, CA.

Ruble, L., McGrew, J. H., & Toland, M. D. (2012). Goal attainment scaling as an outcome measure in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(9), 1974-83. doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10803-012-1446-7

Steinbrenner, J. R., Hume, K., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. W., Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy-Özkan, S., & Savage, M. N. (2020). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice Review Team.

Suhrheinrich, J., Schetter, P., England, A., Melgarejo, M., Nahmias, A. S., Dean, M., & Yasuda, P. (2020). Statewide interagency collaboration to support evidence-based practice scale up: The California Autism Professional Training and Information Network (CAPTAIN). Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(4), 468-482. doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1796545

Yost, D. S. (2006). Reflection and self-Efficacy: Enhancing the retention of qualified teachers from a teacher education perspective. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(4), 59–76. www.jstor.org/stable/23478871