The Researcher

A lot of people do not like Autistic people. Which is a common topic in Autistic spaces. But many allistics who want to advocate with us, as allies, stop talking to me when I mention attitudinal barriers to accessibility. Or else they find creative ways to avoid the topic.

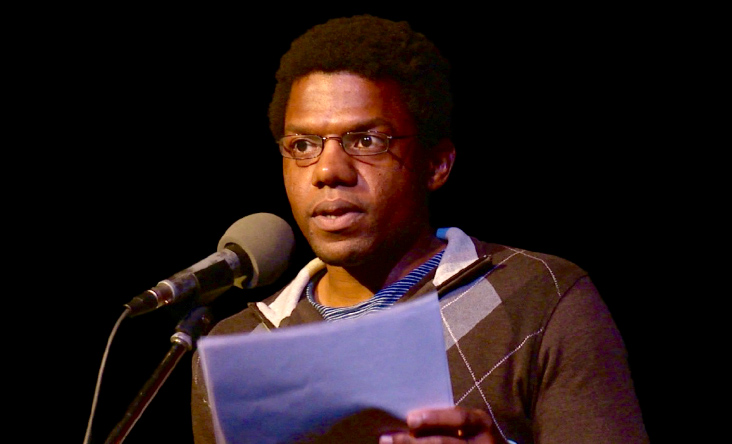

Bernard Grant reading short fiction in Downtown Seattle as a Jack Straw Fellow in 2015

Like last summer, when a postdoctoral researcher asked me what I thought was the biggest problem Autistic children faced. I mentioned attitudinal barriers, bigotry.

“What else?” she asked. As if research means rejecting answers you dislike in favor of the answer you’d prefer.

I reminded her that she asked me about one problem, the biggest problem, and explained that autistiphobia causes the most problems for Autists. I recalled but didn’t mention an episode of the Autism Stories podcast in which Michelle Baughman notes that Autists can’t live as their authentic selves without experiencing ostracizing and bullying because we live in an ableist society where the neuromajority instantly dislikes us (Blecher, 2021).

She reads from Emma Wishart’s memoir “But You Said…?!”: A Story of Confusion Caused by Growing Up as an Undiagnosed Autistic Person, reflecting my own experiences:

“It seems that there’s something indefinable about Autistic people that some other people can immediately sense without even talking to us some kind of aura of our differences. Some people are just instantly made uncomfortable by us, whether it’s our different ways of expressing ourselves, our “incorrect” body language, or something even more vague, such as a feeling.”

Some people are repulsed by us. They make this judgment subconsciously and instantly within milliseconds of meeting us. This happens to me a lot but happens to be most noticeable when I’m upset. As a result, I’ve learned to never show any emotion in public. Something similar may lead many people to the erroneous assumptions that Autistic people don’t have emotions. In truth, many of us have emotions so enormous and tumultuous that we have to keep them strictly in control at all times.”

Avoiding showing emotions in public is a form of masking, passing as nonautistic, like how many queer people have historically passed as straight to avoid stereotyping, discrimination, bullying, exploitation, and death. Codeswitching. Camouflaging. Adaptive morphing.

Masking, while Autists can and do choose to do so consciously, is often an unconscious trauma response. The practice causes Autistic burnout, mental health problems, self-spite, and identity loss, while teaching the allistics around us that their comfort matters most. The reality is that people who only seem to accept you when you pretend you aren’t who you are do not accept you.

The Employers

Years ago, while working as a caregiver, I drove one of my clients to his first job. He was Autistic, a nonspeaking adult in his early twenties. Each shift, he stood in a warehouse untangling computer cables. The agency thought this would be a great job for him since he liked computers. Though he was the same age as many college seniors and recent graduates and untangling cables is not working with computers – it’s menial labor the company didn’t want to pay (much) for.

Ludmila Praslova writes that discrimination against Autists is a systemic problem, as most workplaces favor neurotypicality (Praslova, 2021). She cites a 2020 report in which 50% of managers surveyed refused to hire neurodivergent professionals even though Autists have proven to be more productive (140%) in the workplace than the neuromajority.

My client was someone who’d hacked into our caregiving agency’s network from his living room – miles away front the main office. He also somehow memorized his mother’s credit card number, which he used to buy digital products.

He hadn’t, however, lived with his parents for two or three years at this time. He rarely saw his parents, as they rarely visited, and he was only allowed to leave his neighborhood for doctor’s appointments and short trips to fast-food drive-through windows and occasionally a short walk.

He mostly remained trapped in his home, understimulated, underestimated, and pathologized as someone who supposedly “couldn’t understand anything.” Never mind that if he wasn’t researching online or taking apart and resembling his computer, he spent his time watching nonfiction TV shows on technology and culinary arts.

This young man was clearly intelligent, focused, and interested in how things worked. Somehow no one around him seemed to see his intelligence. Or his adultness. Everyone treated him like a five-year-old, the way many of them often treated me, speaking to us in the voices and language they reserve for babies and small children.

The Psychiatrist

My psychiatrist told me I’m “very stable.” Three months later, he said he wanted to prescribe antipsychotics. When I asked why, he said he wanted to treat my social phobia.

“What social phobia?” I asked.

“Your autism.”

As if there’s some inherent link between an Autistic neurotype and social anxiety. What he was responding to was my lifestyle of rarely leaving my home. Staying home affords me comfort, joy, and the predictability and productivity I need to live and work well. I love working.

I also love my home as I’m less disabled inside my home where I can control my environment. And it makes sense to spend most of my energy here if I spend the bulk of my energy earning money to pay for this home.

There’s also a pandemic, multiple viruses sailing in our air.

I also told him I hadn’t experienced social phobia in years, that autism is not an illness and needs no treatment, and reminded him that I come to psychiatry to treat my trauma-based depression and anxiety.

Treating autism is like treating homosexuality: bigoted and nonsensical. It makes no sense to treat a person’s core self. Treat the problems that harm that core self.

Our Society

Society talks openly about racism and homophobia. So, I often wonder why so many inclusion discussions, especially mainstream discussions, avoid the reality that the reason Autists struggle to find and maintain stability in school, at work, and even at home and in their communities is due to the negative attitudes people have towards us.

This is bigotry, neurobigotry. Autistiphobia. Ableism takes many forms, yet Western society ignores this reality, as Johnathan Mooney observes, writing for New York Times (Mooney, 2019):

“We know more than ever about the long-term effects of systemic sexism and racism. But do we fully understand, and condemn, the effects of systemic ableism? Do we even call it that? I don’t think so. In 2001, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett that there was no history of systemic discrimination against people with disabilities.”

Disability is largely a result of how people interact with their environments. When we talk about the problems Autists face, much of them are caused by Autistiphobia. Bigotry at school and work lead to depression, (social) anxiety, financial insecurity, and suicide. Police find us suspicious (Knapp, 2021). Many allistics find themselves anxious around us, if not repulsed, and try to change our behavior. Which can make us anxious.

The ease with which I understood my Autistic clients as a caregiver a decade ago left a profound impression on me and helped me realize why I’d always felt like an alien. These days, as a life coach, when I find myself involved in a back and forth of relaying messages between allistic parents and their Autistic children, I understand that cross-neurotype communication amounts to cultural differences, not any kind of “deficit.”

People understand this about migrants. But the medicalized deficit model blocks many from seeing Autists as a social group, one united as an ethnicity. No one is independent. We are all interdependent. So, Autists won’t be enabled until the people around us learn the neurodiversity paradigm and change their attitudes towards us. Until society changes its attitudes towards us, I will continue to advocate for inclusion.

Bernard Grant is a writer, editor, and neurodiversity advocate (www.linkedin.com/company/writerly-nourishment). Learn more at their website BernardGrant.com, LinkedIn, or send an email to BernardGrnt@gmail.com.

References

Blecher, Doug. (Host). (2020, December 28). Michelle Baughman (No. 104) [Audio podcast episode]. In Autism Stories. Autism Personal Coach. https://anchor.fm/autism-personal-coach/episodes/Autism-Stories-Michelle-Baughman-eo90fl

Discrimination Does. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/12/autism-doesnt-hold-people-back-at-work-discrimination-does

Knapp, Johnny (2021, July 18). I’m Still Autistic. I Still Fear Cops: One Year After Linden Cameron. Autistic AF. https://autisticaf.me/2021/07/18/podcast-im-still-autistic-i-still-fear-cops-one-year-after-linden-cameron/

Mooney, Jonathan (2019, October 9). At Risk in the Culture of ‘Normal.’ New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/09/opinion/learning-disability.html

Praslova, Ludmila (2021, December 13). Autism Doesn’t Hold People Back at Work. https://hbr.org/2021/12/autism-doesnt-hold-people-back-at-work-discrimination-does

I feel so Isolated since I got my diagnosis in December of 2021. It was handed to me as a platter, so you say. Although, I was shocked but happy in a way, because I felt so different. Parenting kids into adulthood, working, an alcoholic, narcissistic husband. Etc, etc! I’ve had it hard and then some. My child died in 1997, I truly didn’t recover well from losing her. I’ve masked all my life and then even more when I found out. Because people were racist of the, “You don’t look autistic, I thought “those” people rocked themselves,” attitude. This was said multiple times to me. So I masked all the more. Now I live in a village of 2000 people, well again I feel I can’t be my authentic autistic self. There are 2 men housed in group homes here and very extreme in behavior. That is how everyone now sees autism here. What to do, what to do?? I have know idea, but I’m writing a novel about it. And sometime in the near future, I have a children’s series coming available, here in Canada. Any help or suggestions I’d love to here them.

Bailey