I tried to “write” my first book (or more accurately, dictate a story to parents who wrote it down on the bottom third of blank sheets of paper, leaving room for me to add illustrations later) when I was four years old. I started discussing what would become I Overcame My Autism and All I Got Was This Lousy Anxiety Disorder with my agent when I was 36. I crammed a lot of fanciful, expansive, and artistically indulgent visions for my first book into the 32 years between those moments.

Sarah Kurchak

When I finally had a concrete opportunity to realize a version of this lifelong dream, though, none of them felt right. For one thing, I simply didn’t think that my life had been interesting enough to merit a more straightforward memoir packed with deep internal reflections and tied up with fancy prose. More importantly, though, when I looked at the number of autistic people who had been given opportunities and platforms to tell their own stories and I compared it to the number of autistic stories that desperately needed to be told, I couldn’t stomach the idea of making my book entirely about me.

When I began writing about autism for various outlets, I discovered that I had a knack for using fragments of my own stories to illuminate issues that were of importance to many autistic people. I’d start with an anecdote about how pop culture had helped me understand and relate to other people, then move into a bigger discussion about the impact that a character like Julia, the openly autistic Muppet on Sesame Street, could have on younger generations. Or I’d write about my own harrowing diagnosis story in an effort to highlight how inaccessible and unaffordable testing is for so many people, and how hard life can be for the people who slip through the cracks.

Feedback is always a mixed bag for writers, especially those of us who do a lot of work online, but some of the responses that I received from non-autistic people about my work were genuinely heartening. Every “I’d never thought about it that way before,” and “this really helps me understanding,” and “I want to learn more” made me believe that there really were people out there who were curious and empathetic about autistic people and our lives. As I apparently had some ability to reach readers like that, to tweak their perspectives, expand their knowledge and whet their appetite for more, I figured I needed to do even more of it.

So I applied the formula to my book. I would write a series of loosely connected essays, each one using moments from my own life to tackle a bigger topic, ranging from the impact that parents’ choices can have on an autistic child’s life (and the impact that parents’ circumstances can have on their ability to make the right choices for their kids) to masking, to lying, to figuring out how to have reciprocal relationships when the world has told you that you aren’t worth anything, to drinking, to love and sex.

When it came time to figure out how to put these essays together in a cohesive collection, putting the stories in chronological order made the most sense to me. I suspect that’s why the word “memoir” snuck onto the cover. I can’t entirely disagree with the label. It is a story of one person’s life told in a somewhat cohesive manner. But I still hope that people get more out of reading it than that singular narrative.

Sure, I’d love for readers to come away from the book dazzled by my caustic wit or moved by personal reflections, but what matters most to me is that people come away from this book thinking about more than just me. I don’t want anyone to put it down and think, “Wow! I’ve learned everything there is to know about autism now. Time to move on to the next subject!” Nor do I want them thinking that one person with one book can hope to provide all of the information that autistic people desperately need the world to understand and hopefully address.

My hope for my book is that autistic readers come away from it feeling a little less alone in the world, and that non-autistic readers come away from it realizing that they knew even less about autism than they thought they did, and eager to learn more from as many autistic people as possible. My dream is that the book emboldens more autistic people to tell their own stories and inspires more non-autistic readers to be open to those stories. And that maybe all of this can start to build a world where the next generation of autistic voices – speaking and non-speaking, of all support needs, all races, all genders, all sexualities, and all classes – can be supported and celebrated in whatever stories they want to tell, however they choose to tell them. A world where the kinds of choices I had to make when I was writing this book are a relic of the past.

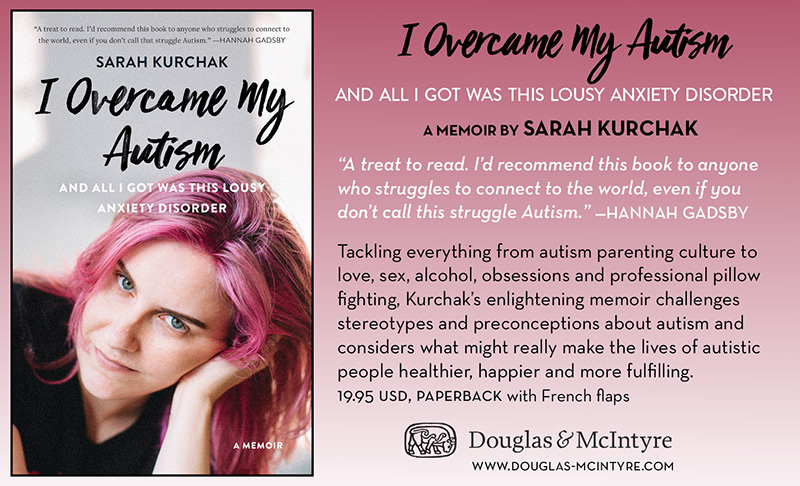

Sarah Kurchak is a writer and retired professional pillow fighter living in Toronto, ON. Her work as an autistic self-advocate and essayist has appeared in Hazlitt, Catapult, The Guardian, CBC, Vox, Electric Literature, and TIME. She is a graduate of the Humber School for Writers, and this is her first book. For more information, visit https://sarahkurchak.carrd.co/.