I have always been sensitive to cultures around me, especially those that remain largely silent or unseen. As a child, I would spend hours watching how crawdads moved together, what dances turtles did when they communicated, and what joy interactive playing brought to jumping spiders – every facet of culture was part of a greater diamond within me.

I define culture differently than I was taught through university textbooks. In fact, I find that it’s difficult to define culture at all because it is so dynamic and alive in every moment, and each tiny culture links to larger and larger cultures around it and moves through it. As an autistic person with a relational way of being, the environment is not separate from any living thing, nor is any living thing separate from any other living thing.

Culture then becomes a point of view through movement, constantly innovated, embodied, and shared… a living organ designed to keep a larger energetic body of relationships connected. It is holographic in nature, in that every single facet reflects every other facet in the universe, ad infinitum – an inconceivably complex and interwoven net of gems that each reflect every other.

In traditional anthropology, a researcher goes into a group of people much different than themselves and tries to put the things that they experience, the things shared with them (willingly or unwillingly) in a box. By definition, anthropology isolates and removes culture from context. As with so many things about neuronormative culture, this approach to learning about other shared ways of being – this reductionist way, this colonizing way of looking at things – never resonated with me. Culture is a mirror. And we are mirrors of culture.

After many years of working as an autistic anthropologist over my career, uncovering unnoticed or under-valued cultures, it was natural that I would gravitate toward an ethnography of my own people, putting all of these thoughts and experiences to work.

An “ethnography” is a formalized acknowledgment, exploration, and recording of the unique shared patterns that give a group of social beings sustained and meaningful cohesion. Ethnographies are generally considered the primary tool of cultural anthropology, and I pondered for some time exactly what an ethnography would look like from an expansive framework.

Synchronicity itself is a part of autistic culture. I met Dr. Roger Jou of the Yale Child Study Center when I was asked to come and speak about my work with gorillas a couple of years ago. He listened with interest to my evolving ideas about the importance of acknowledging and exploring the burgeoning autistic culture (recently exploding with the assistance of technology). We worked together to win a grant from the Connecticut Council for Developmental Disabilities so that I could begin to explore autism as a cultural phenomenon through the autistic social program that he had already established.

Why Is an Autistic Ethnography Important?

Because the shared lived experience of being deeply understood, participating in a shared framework that supports its participants in contributing to the greater good, offering an expanded identity that is a valued part of security, validation, and safety is the ancient birthright of every social being. Moving far beyond utility, acknowledging, documenting, and preserving autistic culture is the right thing to do in and of itself. It is a healing venture at both ends without the need for dissection, a direct service through its own existence.

Even developing such an ethnography, such a cultural program, required serious paradigm shifts. After several iterations, trial and error, and finally opening up to the engagement of every participant, the format finally evolved into the core of the program: invited speakers and facilitators from every background, language, parent culture, socioeconomic bracket, life experience, language, age, and identity, offering workshops, hangouts and think tanks – all recorded for truly collaborative research and for posterity.

Our speakers and facilitators have talked about every facet of autistic culture from birth to aging and brought these facets to life through unique lived experiences: autism in Indian culture, autism as a sensory experience, autism and gender, autism from a First Nations point of view and through voices of Black and brown people, autistic people and their relationship to animals, the creative expressions of autistic people in all of their forms – each have unfurled new maps and new areas of exploration.

What Does Autistic Culture Look Like?

The first thing we learned about autistic culture is that it can’t be put in a box. Throughout the process, everyone was welcome, whether they were self-identified, officially identified by neuronormative people, peer identified, or simply fit with the group, and that soon led to the evident reality that autistic culture is not based on hierarchy. Though I started the ethnography, it immediately became much bigger than me or the sum of the parts as people caught fire with the awareness that they belonged to something real – that we all understood each other and had similar core ways of experiencing the world.

The initial ethnography, now the expanded cultural autism studies program, has revealed patterns of cultural cohesion among autistic people beyond expectation and offers nothing less than a revolutionary shift regarding how we define what autism is and who autistic people are.

There is, of course, actionable utility in the patterns that our cultural autism studies have uncovered and documented, and these patterns are of vital importance toward providing better support and services for autistic people as we live the model: nothing about us without us. We have developed wonderful collaborations with other institutions and autism advocacy groups, working as equal partners with our allies. While its utility is thrilling, it is also thrilling to look at the ways that this momentum was generated from the seeds of its beginnings.

What was evident early on was that the group comprised of autistic people interested in their own culture was taking a different kind of social shape. Occasionally, there was what a non-autistic observer might perceive as “chaos” as people found themselves excitedly talking to other autistic people in a truly supportive environment that saw autism as a cohesive way of being – a deep understanding of each other – our motivations and essence, a shared, functional understanding of the autistic process. There was a real social engagement with a shared, complex network of ideas and experiences. Given a safe space to express their own culture freely, many conventions of neuronormative expression were abandoned. Without the stress of masking and the activation of onion layers of dysfunctional coping mechanisms fomented by a lifetime of cultural oppression, participants felt free to simply be themselves.

One of the first patterns that was evident was that keeping topics and ideas neatly compartmentalized gave way to natural webs of interrelation. “Staying on the topic” looks very different through the lenses of autistic and neuronormative cultures and belies core differences in perception structuring and relevance. So, for example, if the topic is what kinds of sensory spaces work best for autistic people, autistic and non-autistic cultures organize responses to that topic in very different ways. For non-autistic people, “staying on topic” would likely take the form of an hour-long discussion from a “nuts and bolts” perspective (what the dimensions of a room might be, a list of items to furnish it with, etc.). Staying on topic for autistic participants is a more reflective discussion, including connected topics and personal anecdotes about, for instance, bullying, relationships, a time someone was physically hurt on a playground, the tools needed to build an herb garden, and what kinds of pollinators are attracted to various indigenous plants, how someone relates to their service dog, ancient uses of color symbolism, and their favorite stims through the years. To Ethnography participants, these contributions are on topic because, for autistic people, a positive sensory environment is an inextricably linked nexus of emotional safety, physical safety, movement, creativity, the joys of positive sensory immersion, and opportunities to heal from past trauma.

Within this autistic, “neuro-holographic” style of communication, other cultural patterns became evident: a style of straightforward dialogue and a unique rhythm of turn-taking that was strikingly different from those of a neuronormative society. It is clear that natural styles of communication for autistic people require adequate dialectical space and feelings of shared communicative resonance in order to unfold properly. The clash of cultural styles – cultural dissonances-profoundly interferes with intercultural communication and cooperation between autistic people and neuronormative society. This reality in a hierarchical and reductionist system has caused untold trauma to autistic people.

Despite obvious layers of trauma, the warmth and openness of the group have been emotionally moving. The group’s resonance with one another’s creativity, an active enthusiasm for new ideas, unique rhythms of turn-taking, and the natural understanding of one another’s complex emotional workings – these social mechanics, made possible by a forcefully claimed cultural matrix, flowed smoothly from unspoken rules (or, perhaps “value-driven protocols” is a better term). The shared values that underpinned and facilitated the expression and building of autistic culture were quite different from those of a neuronormative society. Most notably, autistic culture is grounded in unusual honesty, genuine and expansive empathy, and palpable respect. When participants had to turn off their cameras, mute sound, walk incessantly during different kinds of sharing sessions, or ask another participant if it was possible to address something in the background that was challenging to them on a sensory level, acceptance and cooperation was a foregone conclusion. When people responded to another person sharing a difficult situation they were going through or a painful memory, offering a personal story of a similar situation or memory was understood to function as an expression of empathetic emotional layers rather than being an example of self-centeredness.

To me, this is the most exciting part of the cultural autism studies program: participants completely reframing and affirming autistic cultural experiences in positive ways. This reframing hasn’t required overt attention, discussion, or procedural consensus – it has flowed from a shared, mindful structure. “Oversharing” transforms into a means of expressing emotional honesty in an efficient and relevant way. “Monologuing” and “restricted areas of interest” become expressions of admirable expertise. “Going down rabbit holes” are lauded explorations of possible new connections or discoveries of meaningful patterns that non-autistic people wouldn’t register. “Outbursts” and “meltdowns” are opportunities for silent support and healing. “Stimming” is a kind of sacred, ritual pantomime for feelings and sensations that defy reductive human speech. “Naivete” and “lack of boundaries” are expressions of the awareness that everyone and everything is connected – an inextricable part of the self.

Autistic people, in general, simply don’t have (and don’t admire) the kinds of invented boundaries and needless disconnections that non-autistic culture manifests from its contrapuntal root. Whether it is on a sensory level, a social level, or a species level – the cultural studies program has illuminated an unusually active sense of responsibility among participants that has hummed into a cohesive force that will have global implications. The program shows that the transformative force of cultural connectivity exponentially enhances our self-esteem, confidence, and the applied energy of these passions.

The energy of these passions is increasing. We open the next academic year with a truly global program, welcoming autistic people and allies (as well as neuro-adjacent people) from Brazil, Italy, England, New Zealand, Ghana, Australia, Senegal, India, Mexico, Canada, Taiwan, Portugal…and the list is constantly expanding. Topics and explorations continue to expand as well. Already this year, we have scheduled autistic psychologists talking about mental health, speakers exploring autistic/animal alliances, specialists in environmental and sensory issues, people sharing life stories of all kinds, facilitators proving space for alternative means of communication, ethics hangouts, physics hangouts, explorations of autistic music, literature, art, and other special interests.

All Are Welcome

This global/holistic orientation of autistic culture should, in my opinion, be embraced not only by anyone who identifies with autistic culture but by a neuronormative society that has obviously run out of ideas for ensuring social equality for all, restoring the living planet, avoiding violence, and restoring compassion, patience, egalitarianism, and creativity. Autistic people are unique pattern processors and problem solvers who often have an inherent talent for finding unique ways of engaging and interacting with the world. An empowered autistic culture, based on these ways of being, has deep significance for the future of all. My hope is that autistic culture, now reified and fortified, can help to heal the wounds that its absence allowed. Cultural Autism Studies at Yale is a place that cultivates alliances between autistic and non-autistic cultures, as well as any program or disciplinary field dedicated to enriching autistic life.

Autistic voices always come first, but people of like purpose are welcomed.

How People Can Get Involved

The best way to get involved is to visit Cultural Autism Studies at Yale’s online Cultural Community Center and the CASY Facebook Page to find our calendar and announcements for exciting upcoming sessions and hangouts. All of the sessions are free and provided on Zoom. Also, check out CASY on YouTube. We invite individuals, sister support organizations from other universities and institutions, and collaborators of all kinds to attend sessions and reach out with their own suggestions.

We are especially interested this year in involving more People of Color, non-speaking autistic people, and other underrepresented groups. We also extend an especially warm welcome to different language speakers to schedule their own offerings through the program.

It is such an exciting time. To be part of this cultural revolution, this steep paradigm shift is unlike anything any of us have experienced. The energy is electric. We hope that you will join us and grow the autistic culture with every voice.

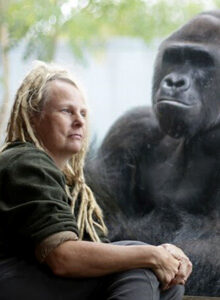

Dr. Dawn Prince-Hughes is Co-Chair of Cultural Autism Studies at Yale. She started her anthropological career learning from gorillas, which led to a long-time association with the Jane Goodall Institute and a PhD in interdisciplinary anthropology in the areas of cultural evolution, universal archetypes, and relational culture. For her work in these areas, she was nominated for a MacArthur Award in 2012. She has written many peer-reviewed papers and several popular and academic books on the subjects of culture, liminality, and radical expansivity. Her best-selling book, Songs of the Gorilla Nation: My Journey through Autism, is now under development as a feature-length film. In addition to her work at Yale, she is working on a new series of books exploring monsters as cultural messengers.