As the world enters a perpetual state of “new normal” due to the COVID-19 pandemic, previously developed routines and coping skills may not be readily accessible – or may not work at all.

College Internship Program (CIP) student and staff work together to organize assignment tasks and schedule study time

Along with the closing of many schools and workplaces, drastically changing societal norms, community restrictions, and frequent fluctuation in how everyday tasks are to be conducted have made the world an overwhelming place to navigate, especially for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Individuals with ASD often find change difficult to manage, particularly when the parameters are not clearly defined. Studies indicate that nearly 40% of young people with ASD are estimated to have at least one anxiety disorder (van Steensel, Bögels & Perrin, 2011). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020), increased levels of anxiety and stress as a result of the pandemic can lead to fear, changes in self-care patterns, difficulty sleeping or concentrating, and worsening mental health conditions.

Stress can impair the most basic executive functions, including short-term memory, planning and self-regulation. Ackerman (2020) describes coping as “cognitive and behavioral strategies that people use to deal with stressful situations or difficult demands, whether they are internal or external.” While many people develop trusted coping strategies that help to self-regulate in times of discomfort, many of these strategies are short-term solutions. Examples of coping strategies include listening to music, deep breathing exercises, drawing, dancing, or even playing video games. A focus on the development of the following executive functioning strategies will reinforce habits that lead to better coping skills.

Organization

Crystal Hayes, MEd

Take inventory – Taking inventory of coping strategies that have worked in past times of uncertainty is a good starting point. Make a list or create a visual toolbox of each coping strategy paired with associated situations or specific feelings. Reach out to teachers and direct support professionals to assist in recognizing coping strategies that have worked at school and in the community. Visually outlining coping skills will help to provide a simple tool for accessing strategies when stress or anxiety are elevated.

Organize Personal Space – Creating predictability in the physical environment can be a powerful proactive coping strategy. As much as possible, identify dedicated spaces for sleep, school/work, leisure, meals, etc. Separating these spaces helps to compartmentalize certain parts of the day that may cause higher levels of stress. For example, the bed should be a place of rest and relaxation. Studying for an exam while lying in bed allows for a stressful task to diminish the importance of self-care.

Planning and Time Management

Most people had established routines and structure in place prior to COVID-19. This ranges from morning hygiene routines, to transitioning between classes at school, to eating dinner at a certain time. Understanding that a change in routine will be a challenge for most, it is important to maintain as much of the original routines as possible. Plan times throughout the day for self-care and coping strategies in order to prioritize personal wellness.

Build Morning and Evening Routines – While unexpected changes in schedule may occur throughout the day, maintaining a consistent morning routine can influence a more positive response to adversity. Utilize a calendar, white board, bathroom mirror, alarms, or other preferred prompts to track each task. Young adults receiving post-secondary transition supports at the College Internship Program (CIP) have reported that pairing music with their routines helps with motivation as well as self-monitoring the time allotted for each task.

Evening routines are essential for regulating sleep patterns and promoting healthy sleep habits. Begin evening tasks early, reduce screen time, and limit tasks that require elevated energy levels close to bedtime. In addition, allot time during the evening routine to reflect on the day and look at the schedule to prepare for the next day. Consider pairing a preferred task with morning and evening routines. For example, include drawing or reading as a precursor to preparing for bed.

Anticipate Change – Support cognitive flexibility and preemptive use of coping strategies by taking the time to anticipate potential changes in expectations or routine. Take note of things that have the potential to change within the structure of the day, week, or month, and discuss reasonable reactions prior to the change occurring. Unexpected change removes control from the person and places control on the environment. Utilization of coping strategies allows a person to control the way they respond to the change.

Set SMART Goals – Setting goals for the future can feel like a daunting task when the future is uncertain. For this reason, it is important to set goals that are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely. Goals that can be completed in an hour, a day, or a week are all acceptable, and completion of these goals can increase self-efficacy and confidence in the ability to move forward despite uncertain circumstances. For example, an individual seeking employment may set a personal goal to complete and submit two job applications by Friday afternoon. This type of specific goal setting allows a person to set their own parameters and maintain a sense of control over their own actions.

Self-Regulation

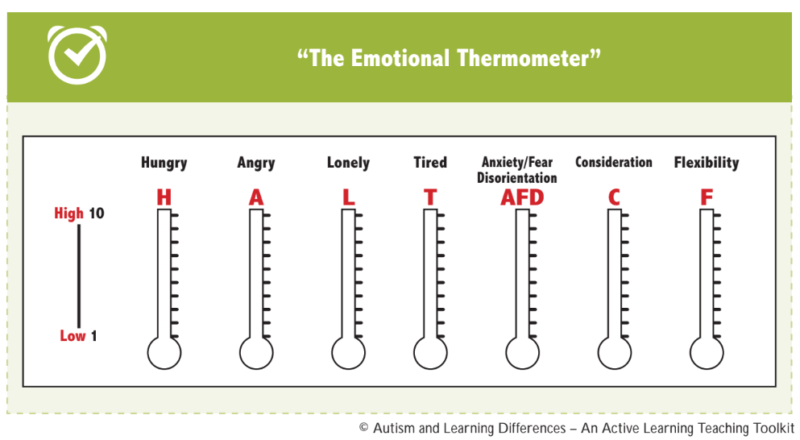

Self-Assess – Referred to as the “Emotional Thermometer” in Autism and Learning Differences: An Active Learning Toolkit (McManmon, M.P., 2016), this tool helps individuals to recognize and identify emotions and respond accordingly. Utilizing this tool daily can help improve self-awareness and build healthy habits. By focusing on specific behaviors that affect emotional regulation (i.e. eating breakfast, talking with a close friend, getting a full night’s rest), individuals can learn to make positive changes that affect themselves and those around them. Other methods of self-assessment include daily journaling, creating a self-monitoring to-do lists, and asking trusted sources (such as a parent, friend, or teacher) for specific feedback.

Conclusion

Individuals with ASD may face challenges coping with stress and uncertainty associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In tandem with trusted coping strategies, development of executive functioning skills can promote flexibility and increased ability to cope in times of change and adversity. Provided the necessary support, positive reinforcement, and consistency, this time can be an opportunity for growth and development for those with ASD.

Crystal Hayes, MEd, is the Interim Program Director at the College Internship Program (CIP) in Long Beach. CIP is a national transition program for young adults with autism, ADHD and other learning differences. For information about their five year-round and summer programs across the US, visit www.cipworldwide.org or call 877-566-9247.

References

Ackerman, Courtney E. (2020, April 15). Coping: Dealing with Life’s Inevitable Disappointments in a Healthy Way. PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020, from https://positivepsychology.com/coping/

McManmon, M. P. (2016). Autism and learning differences: an active learning teaching toolkit. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Stress and Coping (2020, April 30). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 14, 2020, from www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprepare%2Fmanaging-stress-anxiety.html

van Steensel, F. J., Bögels, S. M., & Perrin, S. (2011). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Clinical child and family psychology review, 14(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0097-0

[…] Coping During COVID-19: Strategies to Reinforce Executive Functioning Skills During Times of Change […]