The transition from pediatric services to adult residential care for those on the autism spectrum is a complicated process. Educational systems, healthcare providers, social service agencies, and housing authorities all have a hand in this transition. However, the significant shift is from a system primarily geared toward providing educational and vocational services to one that is more focused on healthcare and social services within the community. And all of this happens in a period that is usually called “the transition to adulthood” (Merrick et al., 2020).

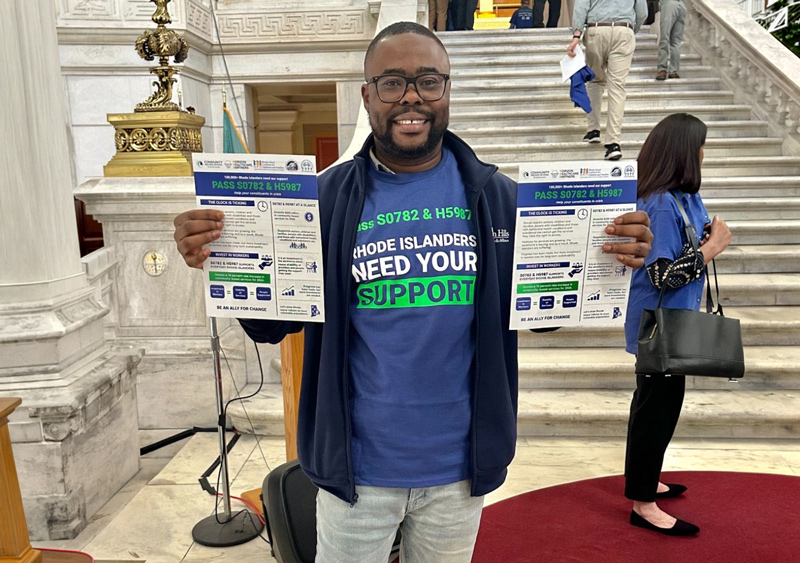

Adusu During Advocacy Season at the Rhode Island State House

Systemic Challenges in Transition

Fragmentation of Services: Typically, children’s programs are coordinated through educational systems under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which mandates that services be provided until age 21. In contrast, adult services fall under a variety of agencies with different eligibility criteria and funding streams, such as Medicaid waivers and state developmental disability services. This fragmentation of services results in a lack of continuity and confusion for families (Havlicek et al., 2016).

Eligibility and Funding Disparities: Generally, for an individual to be accepted into a program of adult residential care, they must meet distinct and sometimes quite strict eligibility requirements. These are at least partly based on the clinical need the individual exhibits (which very often translate into a pathology). These requirements differ in essential ways from those associated with children’s programs. Moreover, even when someone is eligible for adult residential programming, the funding associated with these programs is limited. The individual may need to wait for a period before accessing the necessary and appropriate services (Havlicek et al., 2016).

Lack of Coordinated Transition Planning: Numerous systems lack formal transition planning processes, which often start too late to prepare individuals and families for the change adequately. Without the planning that these families so clearly need, vital pieces of information and support can easily get lost, along with any hope of a coordinated transition (Merrick et al., 2020).

Limited Availability of Appropriate Residential Options: Residential care facilities that cater specifically to adults on the autism spectrum, especially those who have concurrent intellectual disabilities or behavioral challenges, are in short supply. This lack of facilities amounts to a lack of choice that can lead to problematic placements (Micai et al., 2022).

Cultural and Socioeconomic Barriers: Families belonging to marginalized communities frequently encounter extra obstacles. They include language impediments, a lack of knowledge regarding what services are accessible, and biases that are built into our systems. Those obstacles are substantial. They can affect a family’s ability to get quality medical care and the ease with which they can access that care (Wolpe et al., 2025).

Best Practices to Navigate Transition Challenges

Early and Person-Centered Transition Planning: Starting the transition planning process at ages 14-16 offers the convenience of time in figuring out and planning for a child’s future. It gives parents time to come to grips with the choices they are making, and it gives their children time to try on and understand the choices they are making on their behalf and with them (Autism Speaks, n.d.).

Inter-agency Collaboration: Setting up formal collaborations among the educational, healthcare, and social service agencies enables them to share information and ensures that they provide seamless services to individuals with disabilities. Transition teams made up of family members, educators, healthcare professionals, and case managers serve individuals with disabilities well (Arora et al., 2025).

Capacity Building and Training: The quality of care delivered in residential services to individuals on the autism spectrum greatly benefits from the specialized, focused training of staff. This enables direct support professionals and others who work closely with individuals on the autism spectrum to provide the informed, intelligent, thoughtful, and resourceful assistance that affects the day‐to‐day lives of these individuals and their families (Finn, 2020).

Utilization of Technology and Data Systems: Data integration has become a valuable approach for advancing into the human-services space, enabling us to track service access and the service experience beyond the door. Integrated data systems can perform a few basic functions. They can track eligibility for services, waiting lists, and outcomes. They can track all those things in real time, which enables us to do something very different from what I described previously. It allows us to manage transitions.

Development of Diverse Residential Options: Broaden the array of residential places, ranging from supported living to group homes, so that a niche will be created for each child and choice becomes the rule, rather than the exception, and allows people’s real, everyday lives to be the touchstone of their community-integrated existence (Wolpe et al., 2025).

The Role of Advocacy in Removing Transition Hurdles

Advocacy is a tool with the power to effect systemic changes. It can help break down barriers that prevent people from accessing necessary services. Advocacy means speaking up or acting in support of a cause. When it comes to the transition to adult residential services, advocates can take on several important roles. They can be family members, professionals, or even self-advocates. Here are several roles that advocates can occupy:

Working Through Multiple Systems: Advocates help families understand the various components of multiple systems, systemic complexity, to achieve a desired outcome with minimal frustration, confusion, and delay.

Affecting Policy and Funding: Advocacy groups can work together and directly with policymakers to push for more money, more services, and reforms that make transitions into and out of social and mental health service systems smoother.

Creating Awareness and Cutting Down Stigma: Advocacy carries out the work of educating both the communities we live in and our service providers about who we are and what we’re capable of. In turn, this makes for better policies and a better society for all of us.

Enabling Individuals and Families: Organizations that advocate for individuals provide training and resources so that self-advocates and their families can assert their rights and preferences.

Ensuring Quality and Accountability: Advocates oversee residential programs to ensure they meet standards and respect the dignity and autonomy of the people who live in them.

Conclusion

It is essential to ensure there is a smooth transition from children’s programs to adult residential care. It is a rate change, one that sees the individual move from a supervised environment to a less supervised one. By the time the individual has reached age 21, they must show evidence of having completed an education that is equivalent to or better than a high school level. Ultimately, removing systemic hurdles encountered during the transition and continuing advocacy for systemic change is vital in the transition.

Isaac Mawuko Adusu, DHA, MSNPM is a Policy Advocate and Assistant Vice President of Adult Services at Seven Hills Foundation, Rhode Island. He can be contacted at IAdusu@sevenhills.org, ikemawuk@gmail.com, or (774) 823-7151.

References

Arora, D., Berman, M., Snider, L. A., Segall, M., & South, M. (2025). Educators’ knowledge about strategies and supports for autistic students in the transition from school to adulthood. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5129393 (papers.ssrn.com)

Autism Speaks. (n.d.). Transition to adulthood. https://www.autismspeaks.org/transition-adulthood

Finn L. L. (2020). Improving quality of life through caregiver training and support. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 66(5), 327–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2020.1829860

Havlicek, J., Bilaver, L., & Beldon, M. (2016). Barriers and facilitators of the transition to adulthood for foster youth with autism spectrum disorder: Perspectives of service providers in Illinois. Children and Youth Services Review, 60, 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.11.025

Merrick, H., King, C., McConachie, H., Parr, J. R., & Le Couteur, A. (2020). Experience of transfer from child to adult mental health services of young people with autism spectrum disorder. BJPsych Open, 6(4), e58. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.41

Micai, M., Fulceri, F., Salvitti, T., Romano, G., Poustka, L., Diehm, R., Iskrov, G., Stefanov, R., Guillon, Q., Rogé, B., Staines, A., Sweeney, M. R., Boilson, A. M., Leósdóttir, T., Saemundsen, E., Moilanen, I., Ebeling, H., Yliherva, A., Gissler, M., Parviainen, T., … Scattoni, M. L. (2022). Autistic adult services availability, preferences, and user experiences: Results from the autism spectrum disorder in the European Union survey. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 919234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.919234

Nadig, A., Flanagan, T., White, K., & Bhatnagar, S. (2018). Results of a randomized controlled trial on a transition support program for adults with ASD: Effects on self-determination and quality of life. Autism Research, 11(12), 1712–1728. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2027

Wolpe, S. M., Johnson, A. R., & Kim, S. (2025). Navigating the transition to adulthood: Insights from caregivers of autistic individuals. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 55(1), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-06196-z