Those in the autism community are familiar with missed social connections, but misunderstood behaviors have the potential to escalate quickly during interactions with law enforcement. A recent study1 found that 1 in 5 young adults with ASD will be stopped and questioned by police before age 21 and about 5% will be arrested. A 2017 study2 found that young people with autism who have serious psychiatric problems are 9 times more likely to have an encounter with the police than do others on the spectrum.

Researchers are testing a virtual reality tool to help autistic teens and adults safely practice and prepare for interactions with law enforcement

Several times a year, we see reports in local or national media involving an autistic individual whose behavior or failure to respond to orders was misinterpreted by an officer, leading to their arrest, injury, or even fatality. These devastating incidents are understandably worrisome for families and caregivers who wonder, “What would happen to my loved one in the same situation?”

Some of the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder – social anxiety, unusual gestures, reduced eye contact and difficulty processing verbal and body language – can resemble a police officer’s standard profile of a suspicious person. Add flashing lights and the blare of a siren and it can be paralyzing for someone with autism who may have extreme sensitivity to light, sound or touch.

It’s therefore critical to teach individuals with ASD at an early age social and safety skills to safely interact with police. While many police departments around the country offer training to help officers recognize and respond to people who have social and cognitive challenges, these trainings are often not mandated, and individuals with ASD rarely receive training that involves active participation.

CHOP autism researchers partnered with tech company Floreo, Inc., and with police departments to create a realistic virtual experience

Researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s (CHOP) Center for Autism Research are taking a high-tech approach to addressing this challenge. With a $1.7 million Small Business Technology Fast-Track grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the scientists are partnering with tech startup Floreo, Inc. to test a virtual reality (VR) program to improve the safety of interactions between police and adolescents and adults with ASD. “Immersive VR gives us a unique and important opportunity to help individuals practice critical interactions that will help them stay safe and improve their ability to live independently in their communities,” says Julia Parish-Morris, PhD, who is leading the study at CHOP.

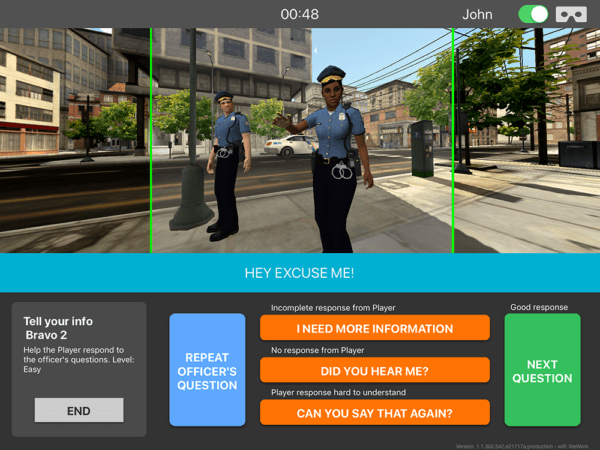

The VR program was developed and refined with input from police officers and individuals on the autism spectrum. It is designed to give users the opportunity to practice social and safety skills for safe interactions with a police officer in simulations that are close to real-life experiences. It will also let parents or therapists observe the user’s behavior and provide feedback and instruction in real time.

“In pilot tests, we found that the VR technology was extremely well-tolerated by participants,” said Dr. Parish-Morris. She explains that for the next phase of the research, set to begin in Spring 2019, “the team is creating a new, expanded VR curriculum that will allow autistic teens and adults to practice interacting with police officers across a variety of different contexts – tall police officers, short police officers, day, night – that’s the beauty of immersive VR.” The researchers are also developing behavioral supports and materials to help participants navigate three sessions of the intervention.

Helping youth and adults on the autism spectrum learn what to do – and not do – during a police encounter will also be an important part of the training curriculum. “For example, individuals with ASD may exhibit differences in eye contact which could be misinterpreted as avoiding questioning or looking for a way to escape,” said Parish-Morris. “The VR intervention will give participants the opportunity to practice these social interactions and a range of appropriate responses, which we know is important for people with ASD.”

“Prioritizing the development of these skills is vital if we as a society want to increase the number of individuals with ASD who are able to live independently, safely and be gainfully employed,” added Floreo CEO, Vijay Ravindran. “We are excited to find out if virtual reality can help these individuals develop the social and safety skills they need.”

More information about this research can be found at CenterforAutismResearch.org. Those interested in participating in this research study may email zittera@email.chop.edu.

CarAutismRoadmap.org provides resources for children, adults, and families seeking evidence-based guidance, information, and support.

Footnotes

1. Rava, J., Shattuck, P., Rast, J., & Roux, A. (2017). The prevalence and correlates of involvement in the criminal justice system among youth on the autism spectrum. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(2), 340-346.

2. Turcotte, P., Shea, L. L., & Mandell, D. (2018). School discipline, hospitalization, and police contact overlap among individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 48(3), 883-891.