Nearly all behavior analysts have come across “non-compliance” within the behavior repertoire of our consumers. Many of us have operationally defined it and targeted it for deceleration. However, how often do we stop to consider the significance of non-compliance? Can non-compliance be adaptive? Can non-compliance have multiple adaptive functions? Can we teach our consumers to discriminate when and how to adaptively communicate “no”?

Applied behavior analysis, or ABA, has received considerable negative press lately, with some of that criticism being an overemphasis on compliance of autistic clients (Veneziano & Shea, 2022; Wilkenfeld & McCarthy, 2020). However uncomfortable as it may be to receive criticism as someone who is committed to work in a helping profession and adheres to the value of applied behavior analysis and evidence-based practices, the field can benefit from listening to these concerns and care can be improved. There is value in assessing the criticism to understand it and clinically reflect on the extent that it applies to our work. This is the only way we can improve our practices as behavior analysts with the people we serve. We need to acknowledge our own biases and learning history. Only then can we move forward and continue to learn and grow as we remain curious and open to learning more as to how our science can improve the quality of life of those we serve.

Rethinking Non-Compliance as Withdrawing Assent

Due to ongoing challenges with appropriate funding and the staffing crisis, time is of the essence more than ever when it comes to the importance of skill-building. This can lead well-intentioned behavior analysts, teachers, and caregivers in wanting every moment to be a teaching opportunity, with little time for “non-compliance.” Non-compliance, however, might be conceptualized as a withdrawal of assent, or a lack of consent, with instruction or another component of the treatment process. Assent has been promoted within the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB]®, 2020) and is now an obligation for both practitioners and for researchers. It is imperative to monitor and gain assent, and to respond compassionately and humanely to any withdrawals of assent. There is room for improvement in the integration of assent into clinical and research work in ABA (Morris et al., 2021). More needs to be done to train practitioners to understand assent, to ensure that assent is integrated into care, and to developing assent procedures for individuals who are non-vocal. A related consideration is to rethink our service delivery to alter our instructional approach. Rather than treat escape-maintained behavior, we should think about how our instruction can be reworked into something individuals opt into (e.g., Rajaraman et al., 2022).

Not only is non-compliance a signal that something needs to be modified with our clinical approach; non-compliance is an essential skill. Teaching “no” and respecting it as a means of promoting a healthy, safe, and well-rounded life is critical. Non-compliance is especially valuable in the context of personal sexual safety, in addition to sexuality education, across individuals, diagnoses, and communication skills (Schulman & Gerhardt, 2017). Simply put, an individual cannot be sexually safe if they cannot be non-compliant. As professionals, we need to reflect on how this relates to the work we do. When non-compliance is targeted for decrease, it can send the message that we do not respect an individual’s “no.” This may further reduce self-advocacy in the form of asking questions, expressing feelings, or engaging in dialogue with us. Unfortunately, we must be mindful of the potential ramifications for harm in this paradigm; it can leave our consumers vulnerable to harm, exploitation, or abuse. For all of these reasons, we need to be thoughtful and re-assess how we can discriminately teach our consumers the value of communicating “no.”

Promoting Self-Advocacy

Time is of the essence when it comes to building skills and independence with autistic children and adolescents; helping our clients develop a repertoire that includes self-advocacy is key. Non-compliance with the command of a functional “no” response that others respect is the foundation of self-advocacy, allowing individuals to advocate for themselves and their needs. A popular disability advocacy site, Covey.org, breaks down self-advocacy simply into the following: Knowing oneself, knowing one’s needs, and knowing how to get those needs met. Non-compliance is endemic in all three parts; self-advocacy cannot occur without the ability to be non-compliant.

In addition to listening to autistic voices and ensuring we are appreciating the nuance of this topic, we need to write better, more nuanced, and collaborative goals with respect with self-advocacy skills at the forefront. Here are some practical starting points:

- Replace references to “non-compliance” with skills to promote instead.

- Alternatively, frame the goal as cooperation instead of compliance, and ensure that it is targeted only when cooperation is important. Drop references to compliance, as it leads to an over-focus on following commands without consideration of choice, assent, or other contextual factors.

- Get curious about why we are observing “non-compliance.” Consider this through a behavior analytic lens and use problem solving to identify elements of intervention that are objectionable to the learner.

- Reflect and reconsider why we value compliance in a particular situation and whether it is even appropriate or necessary to do so in a given context.

A simple first step is to adjust the language we use – both spoken and in written goals. This can be accomplished by replacing “non-compliance” with either cooperation or by focusing on skills to promote and teach while ensuring they align with the individual’s personal goals and desires. For instance, rather than targeting decreasing non-compliance, look to increase pragmatic skills such as negotiation, compromise, safe “no” responses, and problem-solving, all which will promote self-advocacy.

Another objective to consider is to assess the function of non-compliance. This can prompt caregivers, teachers, and clinicians to ask several questions. For instance, is the person having difficulty with the task? Are they experiencing a strong emotion that is preventing them from communicating effectively? Could they be feeling unwell? There are countless possibilities, with some being best responded to with individualized accommodations or assistance. By stepping back and considering why we are observing non-compliance, we can more compassionately let the needs of the person guide us in a collaborative approach.

Also, it is crucial to give careful consideration of our own experiences, perspectives, and biases and how they affect our own behavior. As teachers and clinicians, we must self-reflect on why we value compliance in a particular situation or with a specific skill. Rethinking if it is necessary, considering if it can be done differently, or rescheduling it for later might better respect a consumer’s personal needs or desires. Everyone has life experiences that shape our interactions and expectations; self-reflection and adjustment of our own behavior can help us do better for those we serve.

Working with autistic individuals, we want the best outcomes for those we teach and serve. Listening to criticisms, understanding them, and looking to always do better are essential steps for achieving best outcomes and becoming better behavioral clinicians. Small changes in the language we use can have a large impact; it may be time for the field to de-emphasize compliance and to focus instead on cooperation and collaboration. Finally, the integration of assent, and the assessment of monitoring assent, are now ethical mandates and elements of best practice. It is important to explicitly identify how assent will be gained and how it will be ensured throughout the instruction.

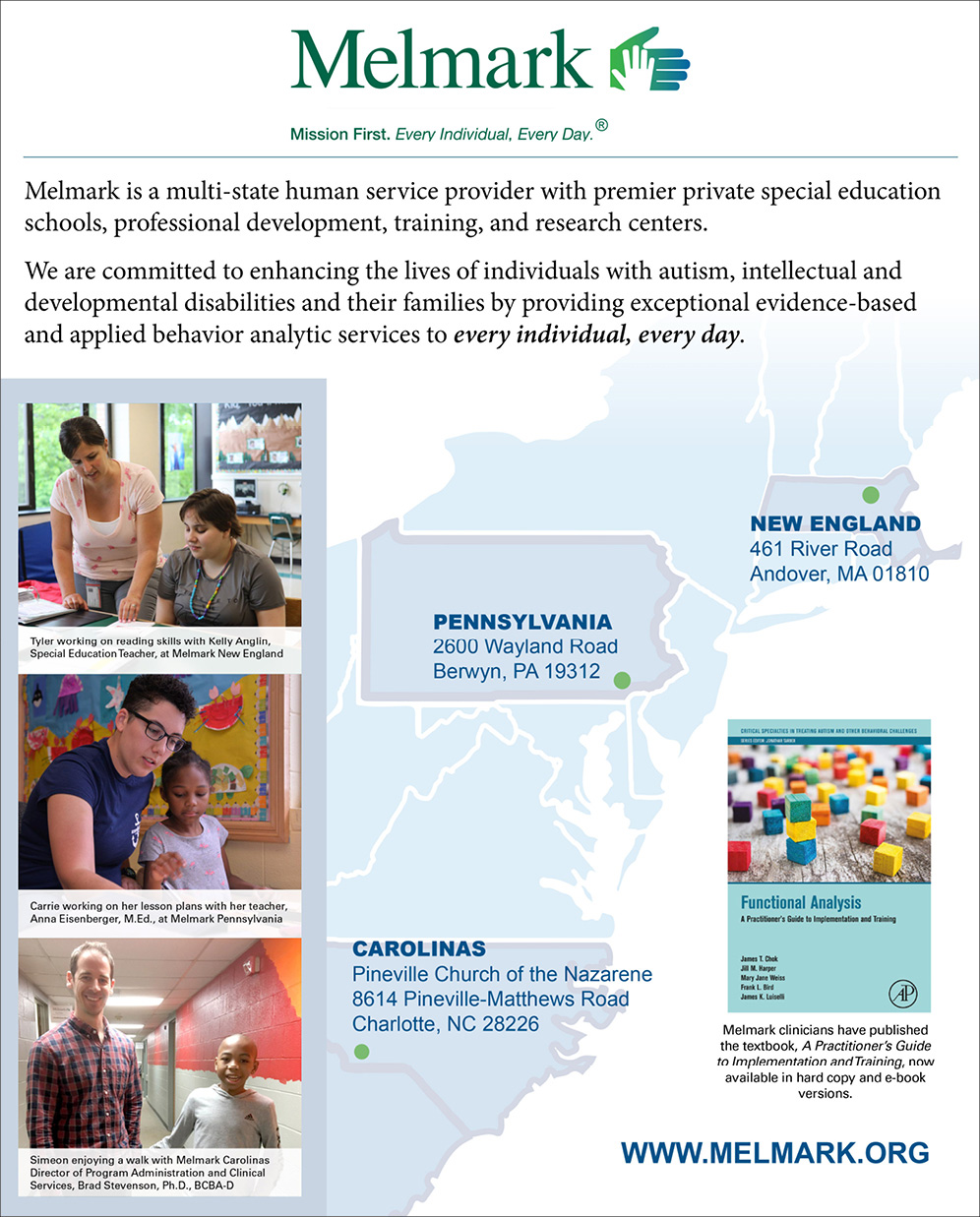

Alex Kishbaugh, MS, BCBA, LABA, is Director of Adult Services and Haley M. K. Steinhauser, PhD, BCBA-D, LABA, is Director of Clinical Services at Melmark New England. Frank L. Bird, MEd, BCBA, LABA, is Executive Vice President and Chief Clinical Officer at Melmark.

For more information, contact Alex Kishbaugh at akishbaugh@melmarkne.org, Dr. Haley Steinhauser at hsteinhauser@melmarkne.org, or Frank Bird at fbird@melmarkne.org.

References

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

Covey. (n. d.). The three parts of self-advocacy for people with disabilities. https://covey.org/self-advocacy/

Morris, C., Detrick, J. L., & Peterson, S. M. (2021). Participant assent in behavior analytic research: Considerations for participants with autism and developmental disabilities, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54, 1300-1316. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.859

Rajaraman, A., Hanley G. P., Gover, H. C., Staubitz, J. L., Staubitz, J. E., Simcoe, K. M. & Metras, R. (2022). Minimizing escalation by treating dangerous problem behavior within an enhanced choice model. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15, 219-242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-020-00548-2

Schulman, R., & Gerhardt, P. (2017, January 1). Healthy sexuality education for individuals with autism. Autism Spectrum News. https://www.autismspectrumnews.org/healthy-sexuality-education-for-individuals-with-autism/

Veneziano, J., & Shea, S. (2022). They have a voice; are we listening? Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-022-00690-z

Wilkenfeld, D. A., & McCarthy, A. M. (2020). Ethical concerns with applied behavior analysis for autism spectrum “disorder”. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 30(1), 31-69. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2020.0000