We want our students with autism to be able to answer the question, “What are you going to be when you grow up?” Vocational training and employment provides a sense of belonging, improved quality of life, community inclusion, and a paycheck. Historically, however, employment rates for adults with autism are low. As the number of individuals with autism has risen over the past decade, a greater number of employers have expanded their hiring practices to include those with autism, recognizing that this segment of the population has both the willingness and ability to work.

Michael J. received vocational training in

retail apparel sorting, folding, and organization

“I think if you’re patient in the training process, and you work with these employees, that you’re going to find you’re going to get an employee that’s going to do a great job for you, show up for work every single day, and be excited about doing their job,” said Damian Smith, District Manager, Walgreens; the second largest pharmacy store chain in the United States.

Here in Massachusetts, like in many states, there are employers who work with autism service providers to provide training and job opportunities for young men and women with autism.

Research has shown that vocational training can make a dramatic impact on an individual with autism’s ability to secure and maintain a job (Wehman et al., 2017).

According to Wehman, et al., at three months post-graduation from high school, 90% of the group that received vocational training acquired competitive, part-time employment. Furthermore, 87% of those individuals maintained employment at 12 months post-graduation. Only 6% of the control group (those who did not receive vocational training) acquired employment by 3 months post-graduation and 12% acquired employment by 12 months post-graduation.

Using ABA in Vocational Training

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is often used to teach children and adults with autism. ABA may help to improve skill acquisition and increase independence, leading to successful employment outcomes.

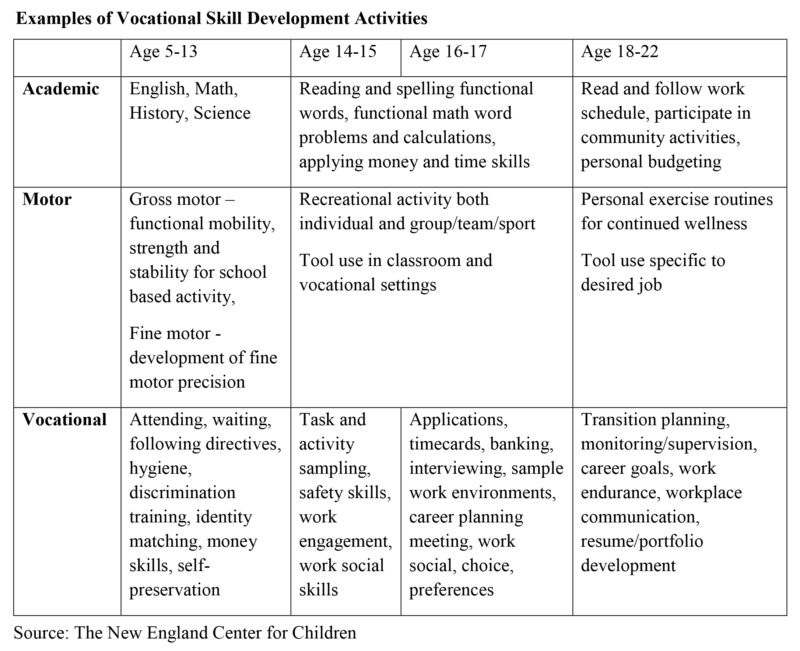

Vocational skill training can help those with autism learn how to follow directions, improve motor coordination, and increase consistency, reliability and concentration. The focus should be on teaching social and functional skills that can transfer from one environment to another. Employment requires a repertoire of soft (social) and hard (job-related) skills. Soft skills include initiating and responding to greetings, conversation skills, responding to social situations, following directions, practicing good hygiene, time management, and dressing appropriately.

Other skills important for the workplace may include money skills, social etiquette skills, communication skills, and job-specific skills. Safety skills, such as fire safety and riding an elevator or escalator, should also be considered.

Establishing Vocational Training Programs

Vocational skill development can begin as soon as State Labor Laws and the Department of Secondary Education Policies permit. In Massachusetts, at the age of 14, students may engage in up to 4 hours per week of vocational exploration within a school or organization. This often starts within on-site career development programs. These programs allow students to explore preferences for work, learn new skills, and gain confidence.

As students age, the amount of time spent on vocational training increases, as does paid and volunteer work. The goal is to develop a strong set of skills and increase work endurance to prepare them for transitioning out of a school program and into the workforce. Students may work in the community or within their school or organization. Potential work options in these environments may include serving or preparing food in the cafeteria, working at the staff copy center, delivering mail, staffing a school store, re-shelving books in the library, or completing light custodial work.

Research shows that a combination of on-site job training and simulation training is most effective (Lattimore, Parsons, Reid, 2006). For those beginning to explore work options, internships and volunteer opportunities are an excellent place to start. Consider volunteering in libraries, animal shelters, nursing homes, civic organizations and small businesses in your community.

State Labor Laws will dictate how much time a student can work per week, depending on their age. For young teenagers, it is often 1-2 hours per week. This time scales up to 20 hours or more for young adults 18 or older.

To best prepare individuals for transition from school to adult programs at age 21, the vocational training program should begin to focus on developing career goals and securing long-term paid employment. Typically, this will begin around age 18. Programs should offer individuals the opportunity to sample a variety of work environments, observe jobs in action, and review occupational handbooks/overviews, as appropriate.

Fostering Employer Partnerships

Relationships with employers can be established by networking with your organization’s board members, employees, friends, and family. Sharing information and providing a tour of your school or organization are also effective strategies. Volunteer opportunities or internships may precede paid employment. With internships, keep in mind Federal Department of Labor regulations. Discuss with employers the needs of their organization or business and how your job candidate can help them meet those needs. Address the practical advantages of hiring individuals for short shifts. Students with autism should receive the same pay, reviews and raises as typically developing employees.

Retail chains are particularly valuable employer partners. These contacts should be cultivated with care and attention. Oftentimes, district managers can direct or influence HR decisions across a region, providing more opportunities for your job seekers. Students may be able to work at one location during their time in school and then transfer to their local community after graduation.

Ensure that the initial employer experience is optimal. Start with one promising student and an experienced on-site job coach to make sure the experience works well for both the student and employer.

After one student has achieved ongoing success, explore expanding the hours and/or days per week for that individual or bringing on an additional student. Job coaches should support the student until they demonstrate mastery of the required skills.

Vocational training is a critical component of autism services that also serves as an excellent way to assimilate those with autism into the community. Local businesses, families and the general public all benefit from working alongside individuals with autism.

Julie Weiss, MSEd, BCBA, LABA, is Director of Vocational Services and Julie LeBlanc, MS, BCBA, LABA, is a Vocational Specialist at The New England Center for Children.

For more information on vocational services programs, contact Julie Weiss, jweiss@necc.org, or visit The New England Center for Children at www.necc.org.

References

Farley M. Cottle, K.J., Bilder, D., Viskochil, J., Coon, H., McMahon, W. (2018). Mid-life social outcomes for a population-based sample of adults with ASD. Autism Research, 11, 142-152

Lattimore, L. P., Parsons, M. B., & Reid, D. H. (2006). Enhancing job-site training of supported workers with autism; a reemphasis on simulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 91-102.

Shattuck, P. T., Narendorf, S. C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P. R., Wagner, M., & Lounds Taylor, J. (2012). Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 129 (6), 1042-1049

Wehman, P., Schall, C. M., McDonough, J., Graham, C., Brooke, V., Riehle, J. E. Avellone, L. (2017) Effects of an employer-based intervention on employment outcomes for youth with significant support needs due to autism. Autism, V. 21(3) 276- 290