The impact of having a child with a disability extends far beyond that individual and impacts the parents and siblings over the course of the family’s lifetime (Harris & Glasberg, 2003: Powell & Ogle, 1985). Developmental disabilities are certainly not universal in how they impact the family, it is universal in that it does have an impact (Feiges & Weiss, 2004; Harper et al., 2016).

Suzanne with her father and brother John

Many parents worry about the effects on siblings, both while they are growing up and when they become adults. They often worry that they are neglected, because of the energy that is allocated to the child with a disability. They may also worry that they feel burdened by the need to support their sibling with a disability, especially after the parents are less able to do so (Harris and Glasberg, 2003).

Indeed, the literature tells us that siblings are affected, and that there are challenges that are common (Meyer et al., 2011; Moyson & Roeyers, 2011; Tanaka et al., 2011). Many siblings experience a wide range of emotions and worry about their sibling and their family (Feiges & Weiss, 2004; Ferraioli & Harris, 2009). However, siblings are insulated by many factors that help with adjustment and adaptation. For example, fostering a sense of fairness is important. In addition, creating a safe space for siblings to express the range of emotions they may feel is essential, and is associated with fewer negative effects and higher levels of coping. Families that can discuss fears about the future and who plan effectively for the future adapt better over time.

While parents concern themselves with the negative impact, it is also true that siblings of individuals with disabilities experience positive effects as well. For example, siblings tend to be more positive, tolerant, and understanding than others. Frequently, they express a sense of mission about making the world a better place and about helping those who are disadvantaged. Many siblings of individuals with autism also report that the disability provided a central focus and a glue for the family, that it helped the family appreciate the positives in life, and that it provided perspective on what is important.

In the excerpt below, the Director of Admissions at Melmark provides insight into the experience of a sibling. Her story illustrates these findings in a personal way that may help families to understand the impact and to plan for the future.

From Suzanne Muench: My Personal Experience

Working with individuals with disabilities was a job I never planned on having. Growing up, I had had enough of being the sibling of a special needs brother and did not want anything to do with it as a career. I went to college to be a social worker, specializing in juvenile delinquency. Little did I know that years later, I would end up not only working in the field, but finding it to be the most rewarding work I would ever do.

My brother John, eight years older than me and born with Down syndrome, was the focal point of our family. He was adorable and stubborn in every way, and demanded a lot of my parents’ attention, as did my other brother, who had learning differences. I was the youngest, and most eager to help out with John. I happily attended and participated in many of John’s therapy sessions hoping to increase the likelihood that I would get attention. I loved feeling exceptionally smart, as I was able to do much of the work they were asking him to do, and it bolstered my confidence along the way. However, because I took a liking to this, it soon became an expectation that I would be involved in many aspects of John’s life and care that I was not always keen on. I was to include him in activities with my friends, be a best buddy in his sports activities, and do it all with an attitude of gratitude that I could do “normal” things that he could not. My mother assumed that I would always be there to take care of my brother, and in the absence of information, I simply agreed, knowing that caring for my brother for the rest of my life was just the hand I had been dealt.

Suzanne and her brother John

As I got older, I realized what a huge undertaking this would be. I began to imagine the impact this would have on the choices I made as a young adult, the relationships I would have, and how I planned a future for myself. I felt very concerned about this as my parents’ health began to decline over the years, but there were never opportunities, or open minds, to discuss alternatives to a plan that was just inherently understood. It would be my responsibility to care for John once my parents were not able to. This was daunting and overwhelming as a young adult with little experience caring for myself, much less someone with John’s needs. There was no expectation that I was entitled to a life of my own, and this brought up feelings of anger and resentment toward my parents and my brother.

Then in September 2011, the phone rang, and my father informed me my mother had unexpectantly passed away in her sleep the night before. This was shocking to all of us on so many levels, but more so because we realized, very quickly, that none of us knew the details of what it took to assure that John’s care continued. Mother was John’s primary caretaker, and we quickly realized that there was a lot we needed to learn, and fast.

Thankfully, by this time I had explored other options in social work and had ultimately ended up working in various positions at a facility that served children and adults with special needs. I had some knowledge of the system for those that had intellectual disabilities, and had some insight into what we would need to do in order to assure that John’s needs would continue to be met.

I was fortunate to be working in this field, and would be able to use my knowledge and resources to navigate through the confusing system of services to advocate for additional support for my father and brother.

Advice for Parents with Younger Children

As an adult sibling having gone through this with my parents, I would like to offer the following thoughts to consider for parents with younger children:

- Offer children choices about participating, or not, in therapy and home sessions.

- Give kids access to age appropriate information about their sibling’s disability. In the absence of information, a child can unnecessarily create erroneous narratives and worry about what will happen to them, their siblings, and their family. These feelings can impact how they perceive their role in the family, and can help them develop coping skills.

- Regardless of the child’s insistence on caring for their sibling “forever,” let them know that you and your family have a plan for future care needs. Let them know that you appreciate and welcome their involvement in developing the plan, but that it will not be their sole responsibility. This is especially important while children are still young and the thought of having to care for a sibling long term could influence their decisions about where to go to college, what careers they choose, how they establish their own families, etc. Siblings may be very reluctant to tell parents that they do not want to take on this responsibility, or that their life choices are being made with these things in mind. Remind siblings that they are entitled to their own lives, and that an identity that is separate from being the sibling of someone with special needs. Let them know that this does not mean they love their siblings any less. In families with multiple siblings, you may find that the neuro typical siblings may not have the same level of interest in their special needs siblings. Let them know that this is okay as well.

- Be honest with children about the fact that having a child with special needs can potentially lead families to feel a wide variety of complicated feelings – including sadness and grief, and that it does mean life may be different from what was anticipated when a new child is expected. Families that can have healthy discussions about these multidimensional levels of feelings can influence how kids cope with these emotions long into adulthood, and increase the chances that the children will be more honest when they can be supported in sharing a wide range of feelings.

- Specifically plan activities with other siblings that are exclusive of the child with special needs. These times will be invaluable for parents and children. These are great times to catch up on what is important in the lives of the other children, and help them develop identities outside of being the sibling of someone with special needs.

- Consider a group for your child such as Sibshops (www.siblingsupport.org) where they can interact with others who are in similar situations. These are great ways for children to connect with others who share similar experiences, and where they can express their feelings in a safe and healthy environment – all while having a space that is their own.

John and Suzanne

Advice for Parents with Adult Children

For those parents who may have children with special needs that are getting older and moving into transitional or adult level services, here are a few things to consider:

- Invite siblings to be involved in small caretaking roles such as short respites, attending meetings, and providing input into what their siblings like or do not like. If they do not want to attend in person, maybe they can offer suggestions ahead of time. For example, the sibling might have insight into what the other sibling might like or not like, especially if the sibling is not able to appropriately make their needs or wants known. If they do not want to participate at all, let them know that is okay, and that you would be open to hearing their feedback and suggestions, when and if they are ready.

- Consider keeping a notebook with important information about the care needs of the sibling. This might include contact information for current service providers, the annual plan, pertinent medical information, etc. Having this information readily available for those left behind can be very useful in a stressful time.

- Make sure your own will and financial affairs are in order, and share this information with your other children. These things are not easy to talk about, but they are even more difficult to deal with in the midst of grief. The time immediately after losing a loved one, especially a parent, can be disorienting for everyone, and having this information sorted out and available will make that process a bit easier on everyone.

- Keep an open mind about future living arrangements for your child. While you may want to care for them at home forever, this may not be a reality. We know that what services and supports are available in an emergency situation are not the same as what can be available when a move to long term care is thoughtfully planned out. Additionally, availability of services, and funding for those services, can have lengthy waiting lists; therefore, the more proactive a family is about this planning, the better. Having families involved in these planning decisions early on, may also help the young adult with special needs to feel as if the transition is “okay” with the family. This, in turn, can give siblings further permission to naturally move on in their own lives, to be able to experience new things without feeling like they have this large responsibility looming over them. Consider these transitions to be similar to the experience of going off to college or moving into their own apartment. If appropriate for your child, making these arrangements sooner, rather than later, can help assure that when the time comes that you are no longer available to manage their care, plans are in place. Involving siblings in these decisions can give them a better handle on what their role and responsibility might be, once you are no longer able to be involved. If appropriate, there are also legal options for siblings, such as becoming a legal guardian, or Power of Attorney.

About five years ago, while having a serious discussion with my father about placing my brother in a group home, he commented that he wished having a child with special needs came with a guidebook. One that would affirm that it was okay to be scared, nervous, excited, and proud of the child he raised, and assure him we would all be okay if he let him live under the care of someone else. It would also gently remind him that the decisions about what was best for his son was less about what he needed as a parent, and more about what was best for his son long term. The final years of dad’s life while John was in a group home were some of the best years they both experienced together. Dad was able to see his son flourish and grow in his independence with his friends, and he learned to trust that caregivers could responsibly meet his son’s needs-albeit not always in the same way he might. Last year, when dad became terminally ill, he shared that he was at peace knowing that John was cared for, and had siblings that would continue to watch over him, but would not bear the responsibility of meeting all of his care needs. As I moved through my own grief process of losing my father, the fact that John was in a well-established living situation afforded me the space I needed to provide self-care and cope in a healthier manner than I might otherwise have done, had I also had to take care of, and manage, John’s care needs.

There were many difficult and heart-wrenching conversations along the way with my father, but as a sibling, I appreciated that my father was willing to have an open mind about different ideas. He thought carefully about each one, and how they would impact John, as well as the care he personally would ultimately need and require. He allowed me the opportunity to share my thoughts and feelings, as well as my knowledge of the field that contributed to his ultimately making the selfless choice to have John transition into a group home.

While I know that this is my experience as a sibling of someone with special needs, and I am only one voice in a sea of other complex and varying situations, the common denominator remains the same. Families that can have open, honest, and timely conversations about many of these concerns as siblings grow and develop together, increase their chances of everyone having a better outcome than those that leave things to chance. I know that growing up as the little sister of a gregarious, and sometimes, mischievous boy, has helped shape me into the woman I am today. I would not have it any other way. Through sharing my experiences, I hope to offer families a few new ideas about how to plan for the future, while lending a voice to my fellow siblings out there learning to forge a path in their own dynamic lives.

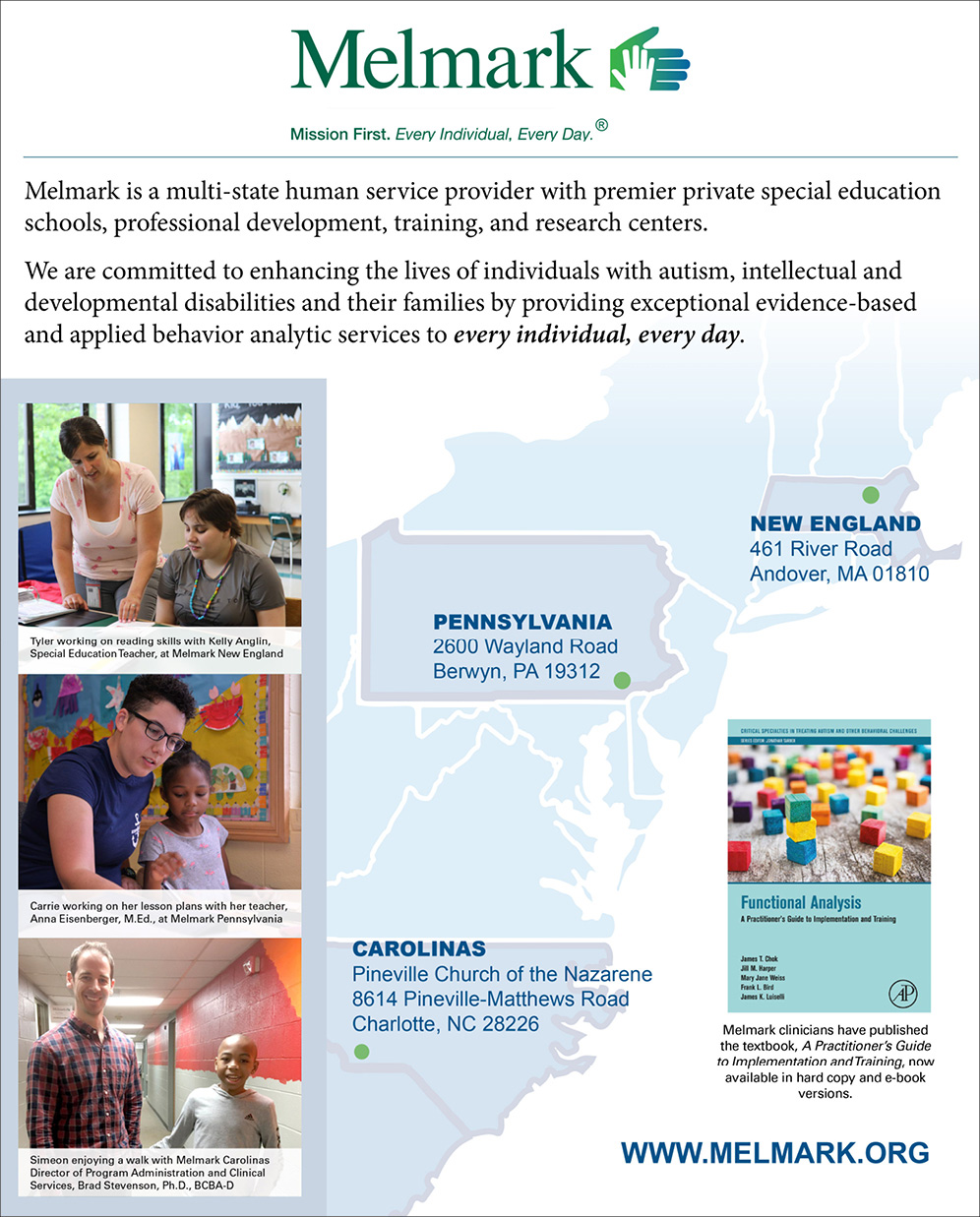

Suzanne Muench, MSS, LCSW, is Director of Admissions and Family Services and Mary Jane Weiss, PhD, BCBA-D, LABA, is Executive Director of Research at Melmark. For more information, please visit www.melmark.org.

References

Feiges, L. S. & Weiss, M. J (2004). Sibling stories: Growing up with a brother or sister on the autism spectrum. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.

Ferraioli, S. J. & Harris, S. L. (2009). The impact of autism on siblings. Social Work in Mental Health, 8:1, 41-53, DOI: 10.1080/15332980902932409

Harper, J. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M. and Jensen, A. C. (2016). Do siblings matter independent of both parents and friends? Sympathy as a mediator between sibling relationship quality and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 101–114. doi:10.1111/jora.12174

Harris, S. L. & Glasberg, B. (2003). Siblings of children with autism: A guide for families. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

Meyer, K, Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick., D. (2011). Factors influencing adjustment in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5: 1413-1420.

Moyson, T. & Roeyers, H. (2011). The quality of life of siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Exceptional Children, 78: 41-55.

Powell, T. H., & Ogle, P. A. (1985). Brothers and sisters—A special part of exceptional families. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

[…] Supporting Siblings is a Family Affair: Thoughts From an Insider to Help Guide the Conversation for … […]