The outcomes for young adults with ASDs are well-known and well-documented. Without intervention young adults with ASD fail to reach basic young adult milestones in terms of independent living, employment, and social and romantic relationships. “Research suggests 70% of individuals with ASD will be unable to live independently, that the cost of supporting each person may exceed 2 million dollars over their lifetime, and that the cost of autism services in the U.S. exceeds $236 billion dollars annually” (Buescher, et al., as cited in Bruyere et al., P.14216). The unemployment rate among this population is staggering. It was estimated that approximately 85% of individuals with ASD are unemployed (Shattuck, 2012). Roux et al., (2013) found that only 53.4% of young adults with autism ever worked outside the home for pay since leaving high school and this was the lowest rate among disability groups. Further, the team found that young adults with an ASD earned an average of $8.10 per hour, significantly lower than the average wages for young adults in comparison groups; and held jobs that clustered within fewer occupational types.

Threshold students, staff and alumni enjoying a Red Sox game at Fenway Park.

They are able to choose among several special events offered at Threshold each week.

Data from the National Transition Longitudinal Study-2 (NTLS-2) indicate that the proportion of young adults with ASDs employed was comparable to young adults with deaf-blindness or multiple disabilities. In fact, individuals with ASDs earned only 86% of what other young people with other disabilities earned. Not only are these young people more likely to be unemployed, but they are also more likely to be underemployed. Half the young people with ASDs worked less than 20 hours a week. That rate is 4 times lower than all other disabilities. On average they worked 23.3 hours per week versus 35.8 hours per week for all other disabilities. This is 36% of the hours that young people with other disabilities work. The proportion of young adults with ASD working full-time is about 1/3 of all other disabilities (26% vs.71%) (Standifer, 2012).

What do we know about encouraging employment and thereby fostering independence among ASD young adults?

Pillay and Brown (2017) identified 4 predictors of employment for individuals on the autism spectrum. Those predictors were: (1) A supported workplace, i.e., a workplace that provides supports such as job coaching in order for the individual to succeed; (2) ASD traits and behaviors (the more significant the autistic traits or externalizing behaviors, the less likely the individual is to be employed); (3) Functional independence; and (4) Family advocacy.

Miligore et al. (2012) found the odds were greater for employment if the individual received job placement services from state offices of Vocational Rehabilitative Services. However, they found only 48% of ASD youth received such services. Furthermore, post-secondary college services were the best predictor of better earning which is critical for independent living. Yet, only 10% of individuals with ASDs in the data set received college-based services. Carter, Austin, & Trainor (2011) found six predictors significantly increased the odds of employment after high school for individuals with severe disabilities: (1) Paid community-based employment while in high school; (2) Being male; (3) More independent in self-care; (4) Higher social skills; (5) More household responsibilities during adolescence; and (6) Higher parental expectations for future work.

Do post-secondary programs work?

The research on the efficacy of these programs is preliminary and limited. Wehman et al., (2013) conducted the first research study where post-secondary vocational training was randomly assigned to students with ASDs. The control group were students who received services through the school district and Vocational Rehabilitative Services Offices. The results showed that 87.5% of the students in the post-secondary vocational training group were employed 6 months after training compared to only 6.25% of the control group who found employment. Moore & Schelling (2015) looked at a group that was not exclusively on the autism spectrum, it did include some individuals with ASD and an Intellectual Disability (ID). Their study found 9 out of 10 students (with ID who graduated from a post-secondary program) were employed within 2 years of the study. This was compared to the respondents to the NTLS-2 study where only ½ of the high school graduates with ID were employed.

Independent living and employment skills are complex interconnected skills that are comprised of more simple building blocks that can be learned sequentially with scaffolded levels of support. College-based transition programs seek to teach those skills to students with ASDs as well as other kinds of disabilities. The curriculum of these transition programs varies. Parents along with their young adults must explore these programs together to ensure that the program will meet the student’s needs and help him or her reach his or her ultimate goals. A key factor is whether the transition program is more academically oriented and leads to a college degree, or whether the program focuses upon life skills including employment and independent living skills. The acquisition of a college degree in and of itself does not guarantee that a student with an ASD will be gainfully employed and be capable of living independently in the community. Transition programs explicitly teach employment skills through classes as well as internship opportunities that are supported with seminars which help the students decipher the social rules of the workplace. Likewise, independent living skills are first taught in the classroom and then are applied to real life settings. Social skills are also taught in the classroom in transition programs and are further reinforced in the residence halls through social programming and in the moment interventions by residence life staff.

The Threshold Model of promoting employment and independent living: A scaffolded approach.

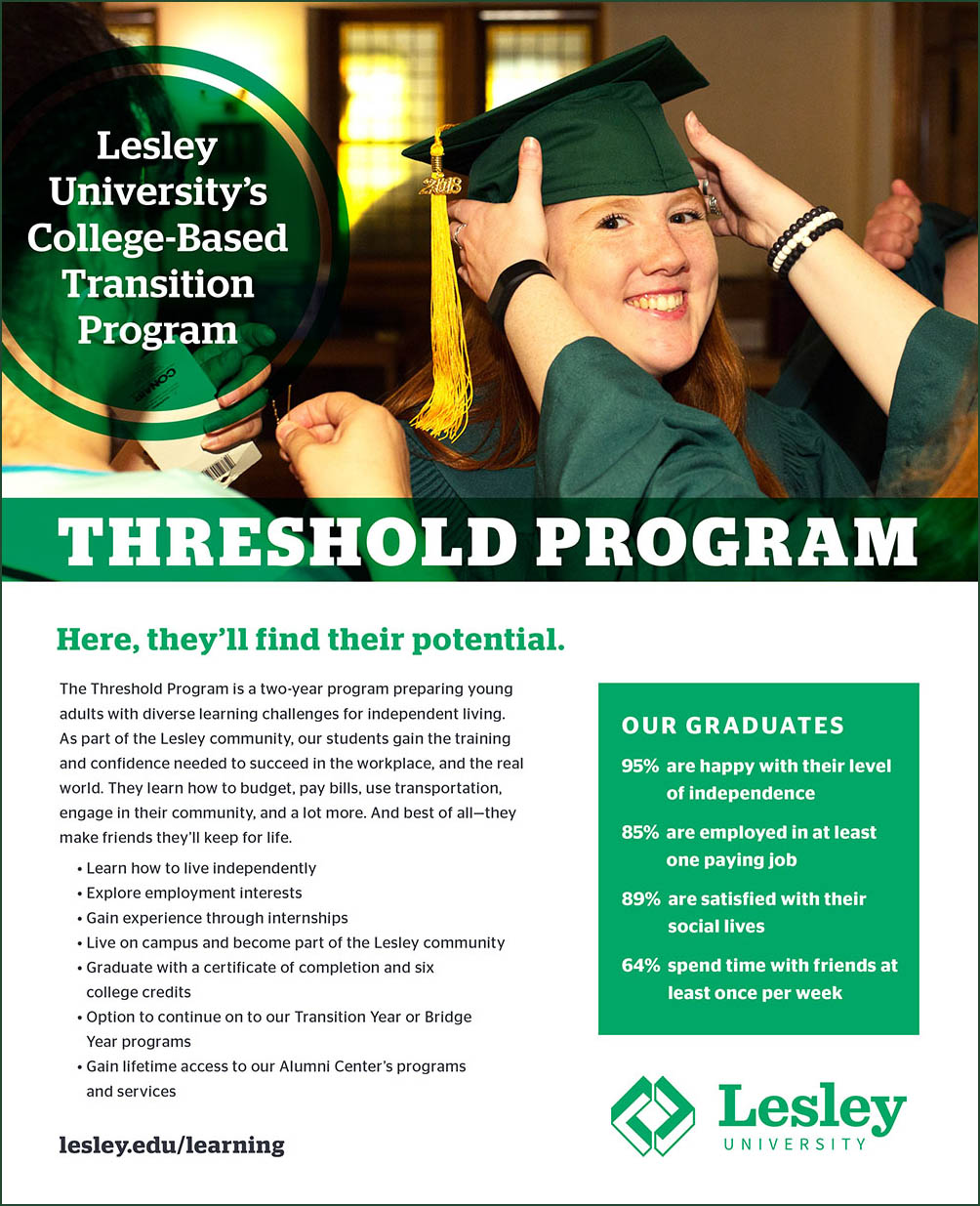

The Threshold Program’s two-year core program focuses on developing social skills, living independently and career training. During the two-year residential program, students participate in pragmatic classes including personal finance, computer applications and food lab and participate in multiple internships tailored to their individual interests and goals. Students live in student dorms and learn to navigate on public transportation and explore their local neighborhoods safely. Lesley University offers an inclusive experience where Threshold students have access to undergraduate courses and can choose to participate in all university activities and athletics.

Threshold students and alumni regularly travel on public transportation to activities and events.

Staff utilize these trips as opportunities to offer travel training. Here they pose at Park Street MBTA station in Boston.

Threshold graduates have two post-graduate options: the Bridge and Transition programs. A small number of students each year choose the Bridge program. In Bridge, students continue to live in the dorms and further explore their internship opportunities during a school calendar year. Bridge Year strengthens work, independent living, and social skills in a structured setting. Most students opt for a Transition year, taking a next step and move into local apartments. Threshold staff assist students to find paid employment and they also remain supported by Independent Living Advisors. Transition students live independently, and Threshold staff meet with them regularly to provide guidance with cooking, budgeting, apartment upkeep, employment strategies, social interactions and accessing local resources.

At the completion of the Threshold Program, all alumni are entitled to a myriad of free services and support from our Alumni Center. Alumni frequently access employment-related support, such as writing résumés or searching for jobs. We also organize workshops and courses. If alumni just want to find something fun to do, we offer consistent social activities with other alumni. Many of our alumni choose to live in the local area to access the Alumni Center but during the recent pandemic we have expanded our virtual services and opportunities to many out-of-state alumni as well.

Our scaffolded approach to independent living has produced exceptional outcomes. In our most recent independent alumni survey, Threshold graduates reported an 85% employment rate. This is drastically higher than the national average. Seventy-seven percent of our graduates are living independently and 38% pay their own rent or mortgage themselves without additional family support. Happily, many of our alumni continue to enjoy Threshold social opportunities and 50% report being in a long-term relationship or marriage.

Ernst VanBergeijk, PhD, MSW, is a professor at Lesley University in Cambridge, MA and is the Director of the Threshold Program which is a post-secondary transition program for students with a variety of disabilities. www.lesley.edu/threshold. He also oversees the Lesley University Threshold Alumni Center which provides life-long support for graduates of the Threshold Program. Beginning Summer 2022 the Threshold Program will be offering a 6-week summer program focusing upon the acquisition of pre-employment, independent living and social skills.

Krista Di Gregorio is the Director of Alumni and Employment Services at Lesley University Threshold Program. The Alumni Center she oversees offers life-long support to all graduates of the Threshold Program. She and her staff also coordinate services for all post-graduate Bridge and Transition program students. Ms. Di Gregorio has a B.S. from SUNY Buffalo and a M.S. in Rehabilitation Counseling from Northeastern University.

References

Bruyere, S., Sonnenfeld, J., Cunningham, T., & Giannantonio (2019). Autism in the Inclusive Organization: Implications for Research and Practice. Proceedings from a Symposium for the Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings.(1):14216. DOI: 10.5465/AMBPP.2019.14216symposium

Migliore, A., Timmons, J., Butterworth, J., & Lugas, J. (2012). Predictors of employment and postsecondary education of youth with autism. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55(3), 176-184. doi: 10.1177/0034355212438943

Moore, E.J. and Schelling, A (2015). Postsecondary inclusion for individuals with intellectual disabilities and its effects on employment. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. DOI: 1744629514564448

Pillay, Y. and Brownlow, C. (2017). Predictors of Successful Employment Outcomes for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 4(1):1-11.

Roux, A.M., Shattuck, P.T., Cooper, B.P., Anderson, K.A., and Narendorf, S.C. (2013). Postsecondary Employment Experiences Among Young Adults with an Autism Spectrum Disorder Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry ,52 (9): 931-939.

Shattuck, P.T., Narendorf, S.C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P.R., Wagner, M. and Lounds Taylor, J. (2012). Postsecondary Education and Employment Among Youth with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 129:1042–1049. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2864

Standifer, S. (2012). Fact Sheet on Autism Employment. Autism Works. The National Conference on Autism Employment. Retrieved from http://autismhandbook.org/images/5/5d/AutismFactSheet2011.pdf . October 15, 2017.

Wehman P.H. et al. (2013). Competitive employment for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Early results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, DOI 10.1007/s10803-013-1892-