Note: This article has been reprinted with permission. You may view the original article, published on November 28th, 2023, at www.neurodiversitypress.com/2023/11/28/ill-always-be-a-sea-creature.

At swim practice, I would pretend I was a sea creature. And when I got a little older, I’d still chase the magic rainbow glimmers at the bottom of the pool with my arms in a tight streamline.

Later still, as I’d silently panic in team meetings, as the fluorescent lights bored holes into the corners of my eyes, and as the energy of the people around me seared through my arteries like battery acid…I would remind myself over and over that I would be fine as soon as I dove in the pool. I just needed the water.

Cathryn Salladin, Former US National Swim Team Member

For as long as I can remember, I have felt like there was something “wrong” with me. I’ve felt like an alien: never quite comfortable, never quite belonging. But I also was never afraid of drowning. I, in fact, have often felt the most alive while holding my breath. In the water, staring at that black line, I could let my mask dissolve. I relished in the buoyant embrace against my body. I worked my muscles to a burn that fueled my self-worth, my identity, my passion, and my dreams. At first, it was just the water, but soon my love became about swimming.

Swimming was the only thing that was truly mine. Homeschooled since 2nd grade, I would spend all day staring at my textbooks, trying to ignore the noise of one sibling pounding at the piano and the other in a screaming match with my mother. I’d plead for time to go by faster so I could escape to swim practice.

I was raised in a conservative Christian environment, where everything related back to Jesus. Until COVID-19, which was when I began to question the way I grew up, I was fully invested: I was involved in church, I believed wholeheartedly, and, just as I was told, I attempted to put my full identity in Christ. When I look back at my dozens of journals between the ages of 12 and 20, I see pages upon pages of self-loathing and depression followed by compulsive prayers and written cries to Jesus to “fix” me.

Looking back at how little autonomy I had over my studies, my religion, my food, my sexuality, and even my personality, it makes sense why swimming became my haven. I had no control over anything in my life except for swimming. No matter how difficult the practice was, I felt safest in that water. I didn’t know then that my aquatic, alien-like feeling was related to my neurodivergence, and that swimming felt like it was my everything because it was my everything. I clung to swimming like the lifesaver it was.

At my very first 10k Open Water National Championships in 2017, I made the National Team, and something shifted. As I signed the papers to commit to representing the United States at the World Championships, the immediate heaviness of the expectation to make it again the next year settled into my body. My name, scrawled in my shaky, 17-year-old signature, was like a branding of sorts — a pledge stating from that moment on, all that mattered was making the National Team again, making the Worlds again, and, of course, making the Olympics someday. Swimming was no longer just mine. Success stole my safe space, and I couldn’t shake the pressure.

When threatened with these demands, my nervous system became unregulated. I have vivid memories of standing behind the blocks before races, frozen and terrified, visibly trembling as I climbed up on the block and took my mark, praying obsessively that I would make it through the race without embarrassing myself; though I would do that in the years that followed.

The more the expectations and letdowns piled on, the more my coach berated me for being inconsistent, for “getting fat,” or “not caring enough,” and the more dangerous my beloved sport became. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was responding out of trauma.

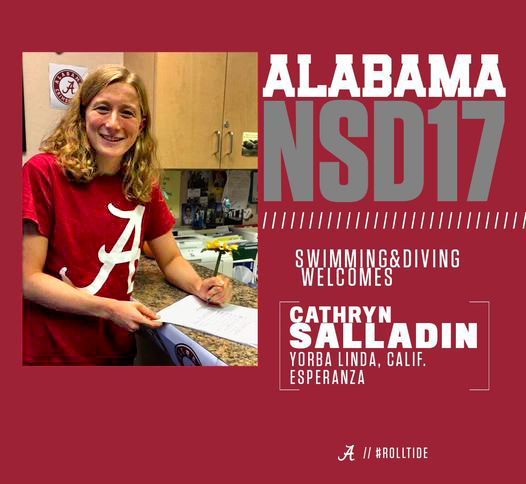

Announcing Cathryn Salladin to the 2017 University of Alabama Swimming and Diving Team

Just like countless other autistics assigned female at birth (AFAB), I was diagnosed with a whole slew of mental health conditions by the time I was 12. I was told I had panic disorder, ADHD, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder. By 16, they’d tagged on “treatment resistant” to the MDD, and by 20, they’d added suspected Bipolar Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder. Not only did I collect diagnoses like Pokémon, but I was prescribed (and unprescribed) countless different medications, treatments, and therapies. From Zoloft to Strattera, from Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Neurofeedback, and from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Brain Spotting. If it’s a treatment for mental health conditions, I’ve likely tried it.

After I made the team, after the World Championships, after a shoulder injury, after surgery, after severe Overtraining Syndrome…practice went from the best part of my day to the worst. But, at the time, I did not have the language, knowledge, or insight to understand why. Why couldn’t I just be like other athletes who seemed to relish in their success and who kept achieving more and more?

As soon as I began my career as an NCAA athlete, the little control I had left over the day-to-day aspects of my training was stripped from me. I wasn’t allowed to decide if I was “sick enough” to miss practice. When I was at my lowest, sleeping less than two hours each night, I was still expected to train. Even my suicide attempt was not seen as a valid excuse to miss practice and that very night, I was told, “See you tomorrow.” Although I transferred schools in hopes of a better environment, more autonomy, and genuine respect — all things that were promised to me when I committed to the school — the culture of the NCAA still pervaded.

Long COVID ultimately ended my career in 2021, but as I was essentially “owned” by my coach and the university, swimming no longer felt safe; it felt dangerous.

Nothing has ever relieved the crushing symptoms I’ve experienced or seemed to fully fit any of the conditions I’d been diagnosed with. That is until I began doing my own research in 2022. Furiously and incessantly, I read and watched anything I could find about autism and ADHD (dubbed, as I found out, “AuDHD”). I was dumbfounded when I came to understand that I was right: I didn’t really fit the criteria for most of those other conditions! When I discovered my autism and discussed it with my providers, everything changed. Now, I have an explanation for why I am the way I am, and it has absolutely changed my life.

As I’ve come to understand my AuDHD brain and my tendency towards Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA), it makes sense that I look back on making the national team as the first crack in my now-fragmented love for swimming. Now, I can understand that it was traumatic to lose the only sense of autonomy I’d ever known. For many autistic people, PDA spawns from a place of trauma, whether it be through our parents, society, or our own apparent lack of control over how we feel. Just growing up autistic can result in our brains and bodies perceiving any kind of demand as a threat to our autonomy and our safety.

In the last few months of my career, when my gut knew it was time to retire but my heart couldn’t let go, I would have flashes of memories from a time when swimming was mine. I would notice the bubbles dancing alongside my body or the sounds of my teammates splashing around me, and I would remember being a sea creature — a sea creature who wasn’t afraid of swimming. The tears that filled my goggles at those memories were out of grief, not just for the end of my career but for everything I lost during those last five years. As I learn more about myself and the role swimming played for me as an undiagnosed neurodivergent kid, the more painful and deeper my grief becomes. I didn’t just lose the sport of swimming. I didn’t just lose my drive for success, my teammates’ camaraderie, or my athletic identity. I lost what gave me autonomy, my deepest special interest, my source of confidence, and the only thing that made me feel that being “an aquatic alien” might be ok. If you swim fast, no one cares if you’re weird.

November 1st marked the anniversary of my retirement, and it still feels like I’ve barely scratched the surface of healing. Even though I avoided anything athletic for months, I still tear up when exercising because my body hasn’t forgotten the dysregulated, panicked state it lived in for years. I know that it is going to be a long road to healing my relationship with swimming and exercise, in general. But it is one that I intend to pursue and see through as long as I am able. Swimming gave me so much joy, purpose, and love for so many years.

I genuinely believe in a future where swimming becomes an integral part of my life once more. I see myself, perhaps months or years from now, holding my breath, diving in, and feeling alive once more. When I feel the overwhelming grief of all that I have lost — my success, my passion, my sense of self — I also have to remind myself of all that I have learned about myself through swimming. There is a facet of hope in all my layers of mourning, a deep knowing that the water is my home, and I will return to it once more. In my mind, I see someone who is older, wiser, and safer, slowly stroking through a lake or an ocean, the fog enveloping them like a blanket of peace. I see someone who is in love with the simple act of swimming once more.

I see my future self.

I see the sea creature.

Cathryn Salladin is a former US National Swim Team Member and current Social Worker and Therapist. She was diagnosed on the spectrum in 2022.