The prevalence of autism has increased dramatically over the last 20 years, with current estimates at 1 in 36 children having a diagnosis or special education classification of autism (CDC, 2023; ADDM surveillance network, 2023). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that all children be screened for autism at their 18-and 24-month well-child visits, and the availability of screening (e.g., M-CHAT) and diagnostic tools (e.g., ADOS-2) has allowed for the accurate diagnosis of autism in children as young as 12 months. Concurrently, it is universally agreed that intervention should begin as early as possible to maximize developmental benefits for autistic children (National Institute of Child Health and Development, 2017; National Academy of Sciences, 2002). We know that the period between birth and age 4 is a time of rapid development where key milestones are acquired during biologically pre-determined windows. Developmental theory suggests that mastery of early skills is necessary as a foundation for subsequent skill acquisition (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2010; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Further, parents have a unique opportunity to guide and support their child’s early development; however, most parents are not naturally familiar with how to facilitate communication, social, adaptive behavior, and play skill development in young children with autism.

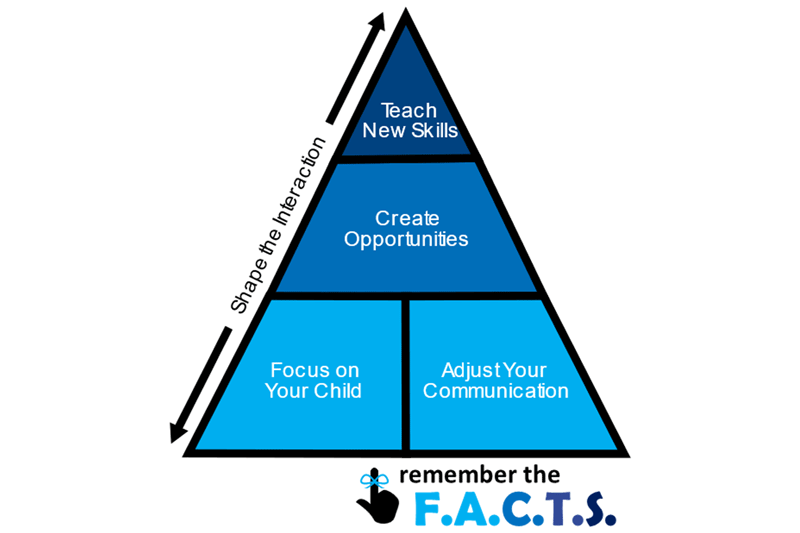

Figure 1. Project ImPACT F.A.C.T.S Pyramid

History of Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs)

Most of the current studies (i.e., in the last 10 years) on intervention approaches for young children with autism or social communication delays are based on behavioral interventions that utilize more naturalistic approaches of Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA). Naturalistic approaches, such as the Early Start Denver Model, Project ImPACT, and JASPER, have shown efficacy (Dawson et al., 2010; Kasari et al., 2008; Ingersoll et al., 2017) as well as effectiveness (Sandbank et al., 2020; Tiede & Walton, 2019) in targeting and improving skills specific to children under age 3 (and up to age 8) with autism. Naturalistic interventions utilize the principles of behavior (e.g., reinforcement, shaping, modeling, etc.) and developmental sciences, which consider the foundational, prerequisite skills needed to acquire new skills and learn from one’s environment. In this way, the intervention target skills are selected using established developmental sequences and naturalistic teaching (e.g., teaching skills in the natural environment and within the context of natural routines).

As of 2015 (Schreibman et al., 2015), these interventions are now collectively referred to as Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs). To be classified as an NDBI, the intervention must be based on principles of Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) and implemented within a naturalistic, developmentally based framework. Concurrently, it requires a manualized curriculum, a structured approach for data collection (pre/post-treatment and during treatment to guide clinical decision-making), and an assessment methodology for therapist fidelity. Meta-analyses on NDBI` interventions indicate positive treatment effects on improving social engagement and cognitive development in young children with autism (Tiede & Walton, 2019; Crank et al., 2021; Dawson et al., 2010; Drew et al., 2002; Kasari et al., 2018; Sandbank et al., 2020). Smaller effects are noted in increasing communication and play skills and overall reduction in autism symptoms (Tiede & Walton, 2019; Ingersoll et al., 2017; Wetherby & Woods, 2006).

Involving Parents in Intervention Programs

Though individually administered NDBI programs yield substantial gains in young children’s development when delivered with intensity (Dawson et al., 2010 & Rogers et al., 2019), they remain difficult for many to access due to resource constraints. As a result, there has been an increased appreciation and need for interventions which leverage parents and caregivers. The American Academy of Pediatrics (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015) strongly recommends Early Intervention for the treatment of autism, including the combination of developmental and behavioral approaches, beginning as early as possible, which also incorporates family and/or caregiver involvement. Teaching parents the skills to promote their child’s development during everyday interactions effectively promotes parents from caretakers to primary mediators and catalysts for change (Nevill et al., 2018). Approaching intervention through parent mediation has significant benefits. This transactional model results in the behavior of the child and caregiver being reciprocally influenced by each other over time. This interaction-based model strengthens the parent-child relationship and enhances parental responsiveness, efficacy, and empowerment (Green et al., 2010; Siller et al., 2013; Sone et al., 2021; Watson et al., 2017; Bryson et al., 2007; Tomeny et al., 2020; Russell & Ingersoll 2021), while simultaneously reducing parental stress (Estes et al., 2014). Parent-mediated interventions also increase the number of learning opportunities for a child. Though many individually administered interventions include a parent training component, at least one randomized control trial has suggested parent-mediated, hands-on training was superior to a parent-only psychoeducational intervention (Kasari et al., 2015), which further supports the need and relevance of a parent-mediated approach, especially during the early learning years.

Using Project ImPACT to Promote Parental Involvement

Project ImPACT (Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2019) is an evidence-based, parent-mediated NDBI intervention program that focuses on Improving Parents As Communication Teachers to build children’s social engagement, communication, imitation, and play skills (Barber, 2020; Schreibman, 2015 & Ingersoll, 2017). Project ImPACT is designed for children aged 1 to 8 who present with social communication delays and current language levels up to about four years of age. The intervention is delivered to caregiver-child dyads over multiple sessions. It has been shown to be effective in single-case designs (Ingersoll et al., 2017; Ingersoll & Wainer, 2013) and group designs (Stahmer et al., 2019; Yoder et al., 2020). Early efficacy has also been established for use in telehealth (Hao et al., 2021) as well as when administered within a group setting (Sengupta et al., 2020). Current research is being conducted on using Project ImPACT within the community (Brian et al., 2022; Pellecchia et al., in press).

Project ImPACT begins with a collaborative goal-setting session between the clinician and caregiver to set realistic short-term and long-term goals in the target domains of social engagement, communication, imitation, and play. The subsequent sessions move through the Project ImPACT F.A.C.T.S. Pyramid (Figure 1), which stands for Focus on Your Child, Adjust Your Communication, Create Opportunities, Teach New Skills, and Shape the Interaction. Project ImPACT incorporates behavioral teaching and parent-child relationship-building activities through interactive and direct teaching methodologies (Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2010; Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2019). Each new skill presented builds on skills targeted in prior sessions, allowing for continued practice of previously mastered strategies. During sessions, parents have opportunities to observe the clinician modeling each strategy and then receive feedback from the clinician as they interact with their child. More specifically, there are seven interactive teaching techniques (following a child’s lead, imitation, animation, modeling and expanding communication, playful obstruction, balanced turns, and communicative temptations), which are designed to increase a child’s engagement and spontaneous communication. Direct techniques include prompting and reinforcement (Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2010; Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2019).

During the initial sessions, the concept of focus on your child is introduced, which places emphasis on building a positive relationship between the child and caregiver. This is achieved by teaching a caregiver to follow your child’s lead and imitate your child’s behavior. By doing so, there is an increased likelihood of social engagement, longer duration of parent-child interactions, and opportunities for vocalizations and language. Once these skills are mastered, parents are coached on how to adjust their communication by using animation and modeling and expanding communication. Using animation facilitates social attention, helps children understand nonverbal communication, and encourages initiation. Frost, Russell, and Ingersoll (2021) also found that when using qualitative content analysis, animation was associated with parent reports of social engagement and child enjoyment. Modeling and expanding communication provides ongoing opportunities for a child to increase receptive language skills while also learning new communication skills. Creating new opportunities involves using a set of strategies to gain a child’s attention before teaching new skills or to help the child initiate during an interaction. This is accomplished through communicative temptations, playful obstruction, and balanced turns. Teaching new skills involves prompting and reinforcement to promote more complex communication or play. Lastly, shaping the interaction teaches caregivers to adjust their behavior by moving up and down the strategy pyramid (Figure 1) based on how a child is responding (e.g., increasing caregiver attunement and responsiveness).

Overall, NDBIs are effective interventions that can drastically change the outcomes for younger learners who have an autism diagnosis. Project ImPACT specifically is an effective parent-mediated intervention which can be used in a wide variety of settings and scales, including clinic, home, and community settings, to help build young children’s social communication, social engagement, play, and imitation skills. It utilizes naturalistic approaches and builds parents’ skills and self-efficacy in engaging with their children with social communication delays.

NDBI Programming in the Autism Center at the Child Mind Institute

At the Child Mind Institute’s Autism Center, we provide a comprehensive range of NDBI services for young children with autism and their caregivers. Our team of developmental specialists – including psychologists, speech-language pathologists, and Board-Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) – creates personalized intervention plans for each child and collaborates closely with home- and school-based providers. For more information, please visit childmind.org or email us at autismprograms@childmind.org.

Alexis Bancroft, PhD, is a licensed psychologist; E. Emilie Weiner, MA, BCBA, is a board-certified behavior analyst; and Cynthia Martin, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist and senior director of the Autism Center at the Child Mind Institute.

References

Barber, A. B., Swineford, L., Cook, C., & Belew, A. (2020). Effects of Project ImPACT parent-mediated intervention on the spoken language of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 5, 573-581.

Brian, J., Drmic, I., Roncadin, C., Dowds, E., Shaver, C., Smith, I. M., Zwaigenbaum, L., Sacrey, L.-A. R., & Bryson, S. E. (2022). Effectiveness of a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a large community implementation. Autism, 26(7), 1882-1897. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1177/13623613211068934

Bryson, S. E., Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Openden, D., Smith, I. M., & Nefdt, N. (2007). Large scale dissemination and community implementation of pivotal response treatment: Program description and preliminary data. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 32(2), 142-153.

Crank, J. E., Sandbank, M., Dunham, K., Crowley, S., Bottema-Beutel, K., Feldman, J., & Woynaroski, T. G. (2021). Understanding the Effects of Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions: A Project AIM Meta-analysis. Autism research: official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 14(4), 817–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2471

Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., … & Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125(1), e17-e23.

Drew, A., Baird, G., Baron-Cohen, S., Cox, A., Slonims, V., Wheelwright, S., … & Charman, T. (2002). A pilot randomised control trial of a parent training intervention for pre-school children with autism: Preliminary findings and methodological challenges. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 11, 266-272.

Estes, A., Vismara, L., Mercado, C., Fitzpatrick, A., Elder, L., Greenson, J., … & Rogers, S. (2014). The impact of parent-delivered intervention on parents of very young children with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 44, 353-365.

Frost, K. M., Russell, K., & Ingersoll, B. (2021). Using qualitative content analysis to understand the active ingredients of a parent-mediated naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention. Autism, 25(7), 1935-1945. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1177/13623613211003747

Green, J., Charman, T., McConachie, H., Aldred, C., Slonims, V., Howlin, P., … & Pickles, A. (2010). Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 375(9732), 2152-2160.

Green, J., & Garg, S. (2018). Annual research review: the state of autism intervention science: progress, target psychological and biological mechanisms and future prospects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(4), 424-443.

Hao, Y., Franco, J. H., Sundarrajan, M., & Chen, Y. (2021). A pilot study comparing tele-therapy and in-person therapy: Perspectives from parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 129-143.

Ingersoll, B., & Dvortcsak, A. (2010). Teaching social communication to children with autism: A practitioner’s guide to parent training and a manual for parents. Guilford Press.

Ingersoll, B., Shannon, K., Berger, N., Pickard, K., & Holtz, B. (2017). Self-directed telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: Examination of the potential reach and utilization in community settings. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(7), e248.

Ingersoll B., Dvortcsak A. (2019). Teaching social communication to children with autism and other developmental delays: The project ImPACT guide to coaching parents and the project ImPACT manual for parents (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Ingersoll, B., Dvortcsak, A., Whalen, C., & Sikora, D. (2005). The Effects of a Developmental, Social—Pragmatic Language Intervention on Rate of Expressive Language Production in Young Children With Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20(4), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576050200040301

Ingersoll B., Wainer A. (2013). Initial efficacy of project ImPACT: A parent-mediated social communication intervention for young children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(12), 2943–2952. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10803-013-1840-9

Ingersoll B., Wainer A. L., Berger N. I., Walton K. M. (2017). Efficacy of low intensity, therapist-implemented Project ImPACT for increasing social communication skills in young children with ASD. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 20(8), 502–510. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1080/17518423.2016.1278054

Kasari, C., Paparella, T., Freeman, S., & Jahromi, L. B. (2008). Language outcome in autism: randomized comparison of joint attention and play interventions. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 76(1), 125.

Kasari, C., Gulsrud, A., Paparella, T., Hellemann, G., & Berry, K. (2015). Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 83(3), 554.

Kasari, C., Sturm, A., & Shih, W. (2018). SMARTer approach to personalizing intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(11), 2629-2640.

Pellecchia, M., Ingersoll, B., Marcus, S. C., Rump, K., Xie, M., Newman, J., … & Mandell, D. S. (in press). Pilot randomized trial of a caregiver-mediated naturalistic developmental behavioral intervention in Part C Early Intervention. Journal of Early Intervention.

Russell, K. & Ingersoll, B. (2021). Factors related to parental therapeutic self-efficacy in a parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: A mixed methods study. Autism, 25, 971-981.

Sandbank, M., Bottema-Beutel, K., Crowley, S., Cassidy, M., Dunham, K., Feldman, J. I., … & Woynaroski, T. G. (2020). Project AIM: Autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychological bulletin, 146(1), 1.

Schreibman, L., Dawson, G., Stahmer, A., et al. (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 2411-2428.

Sengupta K., Mahadik S., Kapoor G. (2020). Glocalizing project ImPACT: Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary outcomes of a parent-mediated social communication intervention for autism adapted to the Indian context. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 76, 101585. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101585

Siller, M., Hotez, E., Swanson, M., Delavenne, A., Hutman, T., & Sigman, M. (2018). Parent coaching increases the parents’ capacity for reflection and self-evaluation: results from a clinical trial in autism. Attachment & human development, 20(3), 287-308.

Sone, B. J., Lee, J., & Roberts, M. Y. (2021). Comparing instructional approaches in caregiver-implemented intervention: An interdisciplinary systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Early Intervention, 43(4), 339-360.

Stahmer A. C., Rieth S. R., Dickson K. S., Feder J., Burgeson M., Searcy K., Brookman-Frazee L. (2019). Project ImPACT for toddlers: Pilot outcomes of a community adaptation of an intervention for autism risk. Autism, 24, 617–632. https://doi-org.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/10.1177/1362361319878080

Tomeny, K. R., McWilliam, R. A., & Tomeny, T. S. (2020). Caregiver-implemented intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of coaching components. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(2), 168-181.

Tiede, G., & Walton, K. M. (2019). Meta-analysis of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(8), 2080-2095.

Watson, L. R., Crais, E. R., Baranek, G. T., Turner-Brown, L., Sideris, J., Wakeford, L., … & Nowell, S. W. (2017). Parent-mediated intervention for one-year-olds screened as at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47, 3520-3540.

Wetherby, A. M., & Woods, J. J. (2006). Early social interaction project for children with autism spectrum disorders beginning in the second year of life: A preliminary study. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(2), 67-82.

Yoder P. J., Stone W. L., Edmunds S. R. (2021). Parent utilization of ImPACT intervention strategies is a mediator of proximal then distal social communication outcomes in younger siblings of children with ASD. Autism, 25, 44–57.

Zwaigenbaum, L., Bauman, M. L., Choueiri, R., Kasari, C., Carter, A., Granpeesheh, D., … & Natowicz, M. R. (2015). Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics, 136(Supplement_1), S60-S81.