Most parents, at some point, grapple with worry over how their child will fair. Will they be happy? Will they find meaningful connections? Will they find their passion? This is particularly true for parents of children with autism. Added to typical concerns, like “is my adult child eating their vegetables and wearing a coat in the winter,” is the worry that your child will not find a place to belong. Individuals on the autism spectrum are found to be significantly more likely to not be invited to social activities or called on by friends than individuals with other categories of disabilities (Orsmond, Shattuck, Cooper, 2013). Twenty-eight percent of young adults with autism interviewed by Orsmond et al., (2013) reported having no social interaction at all. Another study found that limited quality of social relations contributes to higher anxiety levels in those on the spectrum (Eussen, Gool, Verheij, 2012). Some ways to combat social isolation and grow a community is through education, employment, and volunteering. Many neurotypical adults will socialize with those they meet through employment, school, and volunteering.

Charlotte Ochs, MSW

Ernst VanBergeijk, PhD, MSW

Employment

The employment statistics for individuals on the autism spectrum are pretty grim. Without some sort of intervention, the unemployment rate varies widely with rates ranging from 65% – 90% (Chiang, Cheung, Li, &Tsai, 2013; Ohl et al., 2017; Roux et al., 2013; Standifer, 2012; Holwerda, 2012 as cited in Walsh, 2014). The federal government does not track employment and volunteering statistics for individuals on the spectrum. It collectively reviews the employment rates of people with all disabilities. However, the individual must engage in job seeking behaviors within the last 30 days to be considered unemployed.

Persons who are neither employed nor unemployed are not in the labor force. A larger proportion of persons with a disability – about 8 in 10 – were not in the labor force in 2016, compared with about 3 in 10 of those with no disability (U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017b).

Eighty percent of people with disabilities in general are not in the labor force and are not counted as a part of the unemployment statistics. They have given up looking for work which means they have lost an important avenue for community and social engagement.

A few key predictors of employment for this population are whether or not the student on the autism spectrum has had paid employment during high school (Carter, Austin, and Trainor, 2012); had their state office of vocational rehabilitative services present for IEP meetings during the student’s transition-aged years (Roux, Rast & Shattuck, 2018); and completion of some sort of post-secondary education like a college-based transition program or employment program (Moore, & Schelling, 2015; Wehman, 2013). In fact, according to Miligore, Timmons, Butterworth, and Lugas (2012), post-secondary college-based services was the best predictor of earning potential and, however, only 10% of the Vocational Rehabilitative Services database received such services. This group also found that the odds of youth on the autism spectrum finding employment were greater if Vocational Rehabilitative Services were involved in the job placement of the youth, but only 48% of youth on the autism spectrum ever received those services (as cited in VanBergeijk, 2020).

Volunteering

While gainful and fulfilling, long term employment is the ideal and volunteering is a mutually beneficial avenue to gaining job skills, social connections, and giving back to the community. Volunteering can lead to an agency creating a specific job for an individual on the autism spectrum who has contributed to the organization. Or at the very least, can result in letters of recommendation from supervisors and leads or referrals to jobs (Grandin & Duffy, 2004). As part of the college-based transition programs, students and alumni are encouraged to volunteer at a variety of local organizations such as local theaters, food recovery programs and river clean ups. Houses of worship, civic centers, and municipal youth programs are also great places to volunteer and develop social connections. As a group with big hearts and bigger personalities, this group of volunteers leaves a mark wherever they go. The opportunities presented by college-based transition programs as well as a staff dedicated to the holistic success of the students facilitates close, life-long friendships and the opportunity to create and maintain a social circle. From volunteering we have seen relationships bloom into marriages, peers help peers secure employment, and alumni start and maintain traditions for decades.

Finding a College-Based Transition Program

There are approximately 250 college-based transition programs across the country. This number may sound like a large number; however, this is out of over 7,600 institutions of higher education. Unlike colleges and universities where there are dozens of choices per state, some states do not even have a college-based transition program. How do parents, other caregivers, and individuals on the autism spectrum find this proverbial needle in a haystack? The search starts on the internet.

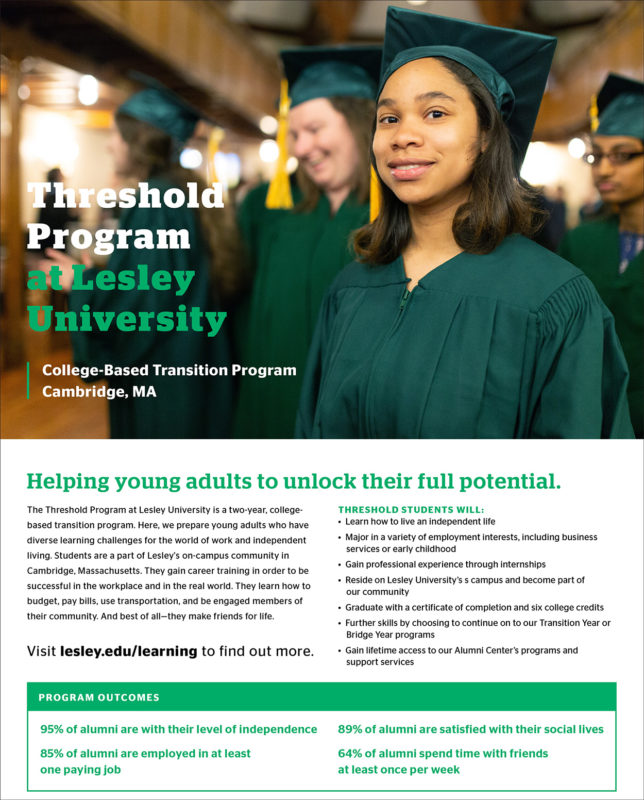

The Institute for Community Inclusion (ICI) at University of Massachusetts provides technical assistance to colleges and universities that have transition programs for students with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. They also maintain a website known as THINK COLLEGE!, which is a repository of information on college-based transition programs. George Washington University is the home to the Heath Center, which is The National Youth Transitions Center clearing house and is an excellent resource for families searching for programs and seeking guidance in their quest for programs. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) web site actually lists the over 75 U.S. Department of Education approved Comprehensive Transition and Post-secondary (CTP) programs by name and location. The CTP status enables those approved programs to provide Federal Student Financial Aid to eligible students with an intellectual or developmental disability. HOWEVER, the aid is in the form of grants and federal student work study monies only. The good news is that those forms of aid do not have to be re-paid. The bad news is that students enrolled in a CTP are not eligible for subsidized and unsubsidized federal loans which make up the bulk of federal student aid. Finding the list of eligible programs is extremely tricky and requires at least 6 clicks from the home page to the actual list. The search engine on this web site is not helpful. Use the following URL to reach the list directly: https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/eligibility/intellectual-disabilities . Lesley University Threshold Program developed an e-Book titled Comprehensive Guide to Transition Programs https://www.lesley.edu/six-qualities, which is available for free.

When searching for a college-based transition program, check to see: What areas of employment and volunteering do they prepare their students for, and does this match your student’s interests? Next, find out what independent living skills do they train students in. Being able to successfully execute activities of daily living such as getting up on time, having appropriate hygiene and dress for work, as well as navigating mass transit to work are better predictors of employment than I.Q. and academic ability. Ask what kinds of support will your student receive if they were to enroll in a particular program. Another key question to ask these programs is, “Will you help with job searches and job placement?” Next ask the program about the program’s outcome data. What are their graduates’ employment and volunteering placement rates? How long have they been tracking their alumni? What percentage of their graduates live independently? How satisfied are their graduates with their social lives and their sense of connectedness to friends and their community? What kinds of long-term support do these programs offer their graduates? By asking these questions, parents along-side their young adult can select the best program to meet the individual’s needs.

Through employment and volunteering, adults on the autism spectrum can have a high quality of life that leads to social connections and community engagement. Many colleges and universities have programs that help students with a wide range of disabilities prepare for the world of work and independent living teaching them not only employment and independent living skills, but also social skills with an eye on community integration. Finding the right program for an individual is going to require a little bit of research on-line and in person with phone calls, with college visits being a part of that process. The right program will have a variety of supports for the individual that may spread across their life span as they grow and age.

Ernst VanBergeijk, PhD, MSW, is a professor at Lesley University in Cambridge, MA, and is the Director of the Threshold Program which is a post-secondary transition program for students with a variety of disabilities. He also oversees the Lesley University Threshold Alumni Center which provides life-long support for graduates of the Threshold Program. Beginning in the Summer of 2020, the Threshold Program will be offering a 6-week summer program for students ages 16-years-old and up.

Charlotte Ochs, MSW, is a Community Support Specialist at The Threshold Program at Lesley University. The Threshold at Lesley University is a non-degree postsecondary program for young adults with diverse learning, developmental, and intellectual disabilities. A graduate of both Syracuse University and Boston University’s Schools of Social Work, Charlotte assists and supports alumni of The Threshold program find and maintain employment, connect alumni to resources, and plan social activities. For more information, please visit https://lesley.edu/threshold-program.

References

Carter, E.W., Austin, D., and Trainor, A.A. (2012). Predictors of Postschool Employment Outcomes for Young Adults with Severe Disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 23 (1):50-63.

Chiang, H.M., Cheung, Y.K., Li, H. and Tsai, L.Y. (2013). Factors Associate with Participation in Employment for High School Leavers with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 43:1832-1842.

Eussen, M. L., Gool, A. R. V., Verheij, F., Nijs, P. F. D., Verhulst, F. C., & Greaves-Lord, K. (2012). The association of quality of social relations, symptom severity and intelligence with anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 17(6), 723–735. doi: 10.1177/1362361312453882

Grandin, T. and Duffy, K. (2004). Developing Talents: Careers for Individuals with Asperger Syndrome and High Functioning Autism. Autism Asperger Publishing Company. Shawnee Mission, KS.

Migliore, A., Timmons, J., Butterworth, J., & Lugas, J. (2012). Predictors of employment and postsecondary education of youth with autism. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55(3), 176-184. doi: 10.1177/0034355212438943

Moore, E.J. and Schelling, A (2015). Postsecondary inclusion for individuals with intellectual disabilities and its effects on employment. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. DOI: 1744629514564448

Ohl, A., Grice Sheff, M., Small, S., Nguyen, J., Paskor, K., Zanjirian, A. (2017). Predictors of employment status among adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Work. 56(2):345-355. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172492.

Orsmond, G.I., Shattuck, P.T., Cooper, B.P. (2013). Social participation among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism Development Disorders 43: 2710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1833-8

Roux, A.M., Rast, J.E. & Shattuck, P.T. (2018). State-Level Variation in Vocational Rehabilitation Service Use and Related Outcomes Among Transition-Age Youth on the Autism Spectrum. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders, pp.1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3793-5

Roux, A.M., Shattuck, P.T., Cooper, B.P., Anderson, K.A., and Narendorf, S.C. (2013). Postsecondary Employment Experiences Among Young Adults With an Autism Spectrum Disorder Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

Shattuck, P.T., Narendorf, S.C., Cooper, B., Sterzing, P.R., Wagner, M. and Lounds Taylor, J. (2012). Postsecondary Education and Employment Among Youth with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics, 129:1042–1049. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2864

Standifer, S. (2012). Fact Sheet on Autism Employment. Autism Works. The National Conference on Autism Employment. Retrieved from http://autismhandbook.org/images/5/5d/AutismFactSheet2011.pdf . October 15, 2017.

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. (21 June, 2017b). Economic News Release. Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary – 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.nr0.htm . October 9, 2017.

VanBergeijk, E.O. (2020). Employment Trends for People with ASD. In: Volkmar F.R. (Ed). Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders (2nd Edition). https://DOI.ORG/10.1007/978-1-4614-6435-8. New York: Springer.

Walsh, L., Lydon, S., and Healy, O. (2014). Employment and Vocational Skills Among Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Predictors, Impact, and Interventions Review of the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1: 266-275.

Wehman P.H. et al. (2013). Competitive employment for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Early results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, DOI 10.1007/s10803-013-1892-