Over the years, technology has improved to create a more immersive environment for users. One more popular trend in technology is the use of virtual reality (VR). Although typically used for gaming purposes, professionals have also found ways to utilize VR for therapeutic purposes. Initially, VR had been used in addition to counseling for exposure therapy for both phobias and trauma (McLean et al., 2022). Now, VR has expanded to other modalities, such as flight training and practice for surgeries. Psychologists have also explored other ways VR can be used for therapy, especially for autistic individuals. This article will briefly cover some of the recent findings on how VR has benefited autistic individuals.

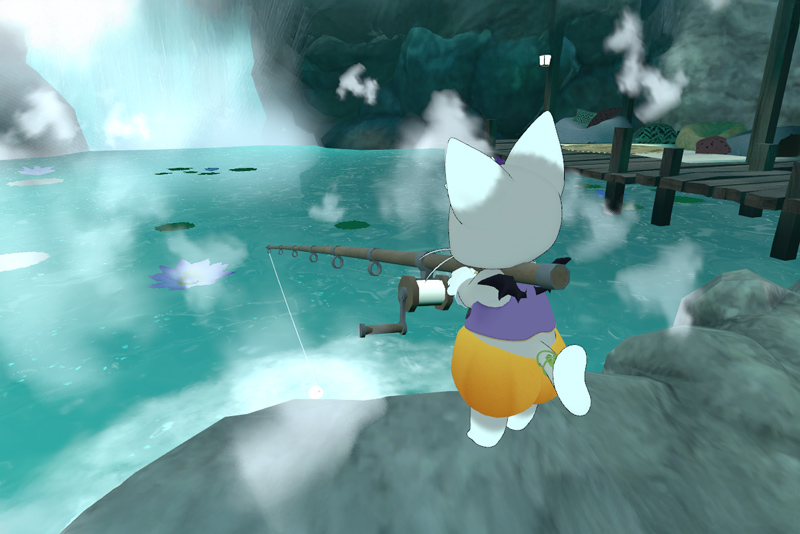

VRChat, a social-based program, allows users to use a custom avatar and participate in leisure activities, such as fishing.

Although VR has been already in use for many decades, recent studies have begun to focus on how we can improve this technology for neurodivergent patients. Current treatment options available may be inaccessible due to funding, limited professionals in the area, and adherence to treatment depending on the level of need (Mittal et al., 2024). In addition, telehealth sessions experience difficulties with maintaining attention during sessions while remaining on a video call. For children with autism, following routines and regularly practicing social and emotional skills are important for learning and keeping the skills they need to interact with kids their age. Current studies have found that therapies that incorporate VR increase motivation and adherence (Mittal et al., 2024). Moreover, VR is adaptive to the individual characteristics that each individual brings into therapy, which is specifically useful for those who are neurodiverse. With that in mind, the options for VR can be adjusted to their needs, providing both immersive and sensory-sensitive activities into their routine (Mittal et al., 2024).

Historically, studies with VR and autistic individuals have focused more on developing social and communication skills (citation, citation). How can virtual reality also help with emotional well-being? More recently, studies have explored ways to teach autistic individuals how to recognize emotions in social contexts. Games and programs have been developed where a person interacts with a virtual human through roleplaying and social interactions (Tsai et al., 2021). While the game shows the player cards with emotions on them, these emotions are then reflected on a 3D model that allows the user to see the emotions in action. Through VR, participants can practice and maintain emotion recognition and regulation, which is important for socializing in day-to-day life (Tsai et al., 2021). Simulated environments for social interactions have been studied as an efficient way to practice

While this article has focused primarily on the emotional well-being of autistic individuals, VR has also been studied on one occasion to see if it could also benefit the emotional well-being of parents of autistic children. For many caregivers, finding time for therapeutic intervention to help with stress can be difficult (Lovell & Wetherell, 2024). Researchers have explored ways in which they can bring interventions to the home that are more readily accessible. Caregivers participated in a study where they were given VR headsets that showed relaxing scenery for up to 15 minutes, such as a forest or a beach (Lovell & Wetherell, 2024). After a weeklong trial of usage, caregivers reported less anger and stress while also reporting higher energy (Lovell & Wetherell, 2024). Although this is a trial study, it is one demonstration of how VR can help caregivers of autistic children cope emotionally.

As an autistic individual myself, I have always wondered how VR can help me with my own emotional well-being. There are numerous social-based games and apps that use VR to allow for socializing in a virtual space. For example, VRChat allows users to meet in virtual rooms and worlds to interact, play games, and socialize across a variety of scenarios. Over the course of four years, I have used this game for weekly social events with online friends. We participate in activities such as fishing, improv, and adventures to fantasy worlds others have created. There are also virtual concerts held on occasion that can be adjusted to the person’s sensory needs, such as volume or how many lights or people are in the room. VR allows these virtual visits to feel real and more immersive than talking on the phone or watching a video. In addition, some extra technology for VR brings in more nonverbal communication, such as full body tracking and face tracking. In my experience, full-body tracking has helped me to express myself more while also helping me to understand how someone else may be feeling in a situation.

Overall, VR has much to offer autistic individuals. Social apps and other programs are an initial start that has helped to improve both confidence and well-being for this population. In addition, researchers have begun proposing other programs that help train autistic individuals for real-life situations. One example is an environmental simulation of working in an office space and how you may interact with co-workers (Abdulbaki Alshirbaji et al., 2024). As VR continues to improve, more technology can be developed that helps with other symptoms of ASD. This may include sensory integration, physical wellness or exercise, and group-based therapies for multiple users at once. Telehealth may also utilize VR to create a more immersive therapy setting for this population and many others. The possibilities are endless and can open doors to opportunities for many individuals.

For those who are curious about VR programs for autistic individuals, below are a few websites with resources of established programs that make use of this technology. I have also provided some VR games that have been developed or are used by autistic individuals. It is important to note, however, that VR is not appropriate for everyone. Those who have sensory aversion to headgear or objects over their eyes, in addition to those more sensitive to motion sickness, may not benefit from VR. Parents and caregivers should also monitor the VR programs their child is using at home, as some allow socializing with real people in a virtual space.

- Floreo – https://floreovr.com – FDA-approved VR program for neurodivergents. They offer training for professionals who wish to incorporate this technology in their office.

- RobotLab VRKit – Provides VR headsets for classroom settings that can create more immersive learning experiences for social and communication skills. Provides training and technology required to apply VR in school settings.

- XR Health – https://www.xr.health/ – Offers telehealth services and therapy through a VR headset, which is delivered to the home. They offer a variety of services based on the individual’s needs.

- BLINNK and the Vacuum of Space – A VR game developed for autistic players, a good way to introduce virtual reality for younger VR users.

- Tilt Brush – A VR game that allows the user to paint and sculpt in a virtual space.

- Beat Saber – VR Rhythm game that allows the player to hit blocks with sabers to the beat of music they enjoy. Difficulties can be adjusted to the player’s comfort level. Provides a lot of physical activity for the player, ideal for all ages.

- VRChat – https://hello.vrchat.com/ – A virtual social app that allows the user to use a custom avatar and interact with people around the world in a digital space. Play games, explore worlds, and meet new friends. This game can also be played with a keyboard and mouse. This program is more appropriate for adolescents and adults.

Jenna Winkelman, MA, is Doctorate Student in Clinical Psychology at Fielding Graduate University. For more information, this author may be contacted via e-mail at jwinkelman@fielding.edu.

References

Abdulbaki Alshirbaji, T., Arabian, H., Igel, M., Wagner-Hartl, V., & Moeller, K. (2024). Emotion-driven training: Innovating virtual reality environment for autism spectrum disorder patients. Current Directions in Biomedical Engineering, 10(4), 5-8. https://doi.org/10.1515/cdbme-2024-2002

Lovell, B., & Wetherell, M. A. (2024). Do virtual reality relaxation experiences alleviate stress in parents of children with autism? A pilot study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(7), 2134-2141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02876-1

McLean, C. P., Levy, H. C., Miller, M. L., & Tolin, D. F. (2022). Exposure therapy for PTSD: A meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 91, 102115.

Mittal, P., Bhadania, M., Tondak, N., Ajmera, P., Yadav, S., Kukreti, A., Kalra, S., & Ajmera, P. (2024). Effect of immersive virtual reality-based training on cognitive, social, and emotional skills in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 151(NA), 104771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2024.104771

Tsai, W., Lee, I., & Chen, C. (2021). Inclusion of third-person perspective in CAVE-like immersive 3D virtual reality role-playing games for social reciprocity training of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Universal Access in the Information Society, 20(2), 375-389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00724-9

Yuan, S. N. V., & Ip, H. H. S. (2018). Using virtual reality to train emotional and social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. London journal of primary care, 10(4), 110-112.