In 2003, I was about to say “no” to the offer to start what would become GRASP. I had been a minor-league diplomat who, throughout the ten years of working for my organization (if you can believe this…), they had gone through five Executive Directors in one six-year period. Twice, I was offered the post at Veterans for Peace, Inc., and twice, I turned it down (we had a brilliant but very difficult board of directors). Being an Executive Director, in my second-hand experience, was an exercise in self-loathing.

Harriet McBryde-Johnson, who was an American author, attorney, and disability rights activist

But while mulling the offer, I read a New York Times Sunday Magazine article written by one Harriet McBryde-Johnson. McBryde-Johnson, a Georgian who had significant enough physical challenges that she required assistance to accomplish basic bodily functions, had in her life risen to become a successful lawyer and disability advocate.

A very famous philosopher, Peter Singer, had been writing about how it would be more humane to kill people like McBryde-Johnson at birth. The justification for him lay in his judgment that her life wasn’t worth living and that it was too full of suffering. Singer, a handsome, best-selling author of several books, a noted animal-rights activist, and a strict vegan, had read McBryde’s writing through the organization she belonged to, Not Dead Yet. And he noticed that in some of her writing, she criticized him.

In response, he invited her to a public discussion that would force her to defend her right to live. The discussion would be on his home turf of Princeton University, where he taught. Should she accept such an awful proposition?

Her article, “Unspeakable Conversations,” chronicled the entire experience. The first line, “He insists he doesn’t want to kill me.” is impossible to walk away from.

That two supposedly progressive causes, animal rights and disability rights, could be such polar opposites is a reality of assumed alliances that our culture has not spent enough time examining. Needless to say, it doesn’t take an enormous investigation to discover that Singer, in both of these causes, assumed that he had the right to judge the value of lives that were anything but his own.

But this is not a unique situation. The disability community has often advocated against physician-assisted suicide and instead for the rights of the victim (whether they are voluntary or not) to live and for more access to treatment for depression or more successful pain medications.

There are even such butting of heads outside disability, wherein we “progressives” get caught being intellectually sloppy, such as the progressive value of organic farming. If the food they put into our grocery stores is more expensive than non-organically-farmed food, then economically challenged people don’t have access to it. By design, if poor people get shut out of any development, then it cannot be progressive.

Margaret Sanger, Planned Parenthood’s founder, believed in eugenics so much that she would have criticized Singer for being too soft.

And then there are topics that are very uncomfortable to Americans, like sex. Some people with disabilities don’t have the use of their hands. Well, how do they accomplish the task of pleasuring themselves without help? Such an examination really challenges our prior perceptions of both sex work and privacy itself. Going further into actual sex, I’m proud to have written the autism world’s “biggest, fattest, sex book,” and I often think of an example I came across wherein two physically challenged people living in an assisted residential space wanted to have sex with one another in full consent…Well, what if they needed a third person to push their naked bodies together?

These are loaded questions that we, as Americans, and not just the disability community, have to become more comfortable talking about. By avoiding them and giving in to our cultural discomfort, we don’t just cause suffering; we run from the stories and narratives that could be the pinnacle of diversity and of humanity at its most beautiful.

Conclusion

Fifty years is a long time. What I’ve asked for thus far really isn’t much. As a matter of fact, with the exception of money spent to make all our structures accessible to all, I’ve been asking for us to trash what we don’t need…infinitely more than I’ve been asking for anything new.

And while a large number of Americans are anything but behavioral pluralists, few of us are true behavioral bigots. I’d argue there’d be little to no objection if most neurodiverse conditions were simply thought of as natural extensions of the human experience in these 50 years.

I am asking us to extend more energy and thought into how badly we still play these cards we’ve been dealt. As we all know, even the nicest and best-intentioned of us can be biased. For example, how many large Diversity & Inclusion departments in universities and corporations actually address disabilities? Usually, these are race and gender equity departments that should be praised for their work but condemned for the gall to call themselves Diversity & Inclusion departments.

Our ideas about inclusion are, at best, in their infancy.

***

Once upon a time, there were campaigns that depicted disabled individuals like this Nazi propaganda poster, depicting the kinds of “defectives” who ended up as victims of the T4 involuntary euthanasia program.

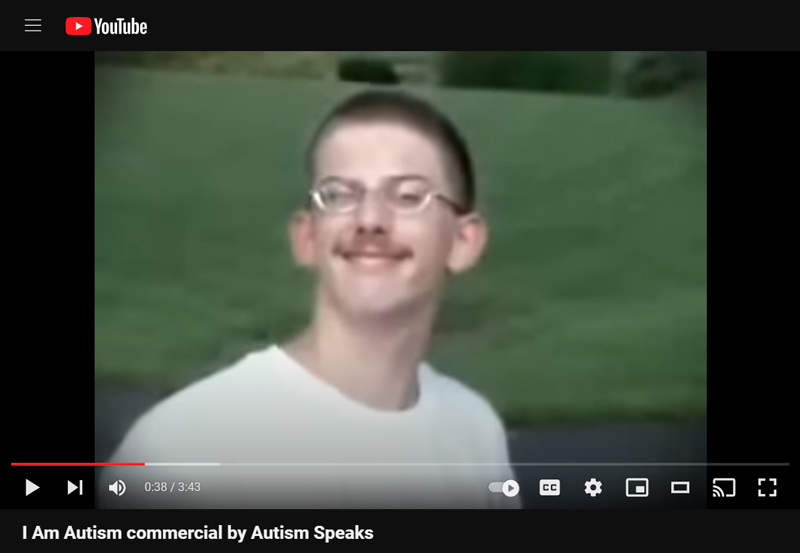

Some disabled people have faces that rest or relax on different expressions. And there is a parlor trick wherein this characteristic can be spun as subliminally equating to demonic possession. It’s a tool used to raise money or to scare (that fear of the unknown again). The still-standing Autism Speaks, as evidenced by the following photo, employed this tactic in their ghastly video, “I Am Autism,” as recently as 2009.

“I Am Autism” Commercial. Autism Speaks, 2009

Mel Baggs (1980-2020) (who used the pronouns “Sie” and “hir”) was one of our earliest heroes in the autism world. Sie was a non-verbal spectrum person who communicated and regularly blogged (as “ballastexistenz”) through a keyboard.

In response to a similar (and short-lived) campaign by the Autism Society of America, sie posted the following picture of hirself.

Photo: Mel Baggs. Used with permission.

Mel then wrote the following:

“This is what I look like when I’m trying to relax, or zone out a little, or shut off vision so that I can hear what is going on around me. I have no doubt that someone could use this image to show the tragedy and despair inherent in autism…Black-and-white images such as these, and the captions that go along with them, are designed to create a reaction. Most often, disability organizations, run by non-disabled people, use them to elicit pity – and money, at the expense of the truth. Look at the autistic person in her own world, they say. Isn’t it tragic? What I am doing in this photograph is no different than someone curling up with a good book to unwind after a long day…Some autistic people would even say that it’s bad to publish pictures that look like this. Better to publish the ones that make us look like real people. Those are the better pictures…I say that plays straight into the hand of people who think there’s something wrong with the way we look.”

What does this say about the unhealthy needs of the “abled”?

Michael John Carley is the Facilitator of the “Connections” program at New York University for their worldwide autistic students, and he also has a private, Peer Mentoring practice. In the past, he was the Founder of GRASP, a school consultant, and the author of “Asperger’s From the Inside-Out” (Penguin/Perigee 2008), “Unemployed on the Autism Spectrum,” (Jessica Kingsley Publishers 2016), “The Book of Happy, Positive, and Confident Sex for Adults on the Autism Spectrum…and Beyond!,” (Neurodiversity Press 2021, where he recently became the Editor-in-Chief), and dozens of published articles. His many other current posts include being the Neurodiversity and Leadership Advisor for the League School for Autism, and he is Core Faculty for Stony Brook University’s LEND program. For more information on Michael John or to subscribe to his free newsletter, you can go to www.michaeljohncarley.com.

Articles in This 3-Part Series

- What I’d Like to See Change in the Disability World Over the Next 50 Years – Part 1: Let’s Change How We Define “Disability”

- What I’d Like to See Change in the Disability World Over the Next 50 Years – Part 2: Know and Teach the REAL History

- What I’d Like to See Change in the Disability World Over the Next 50 Years – Part 3: REAL Culture Change