Having attended many talks, workshops, and education-related autism community events, I often hear the expression “one size does not fit all” used by teachers and other professionals who work with students on the spectrum. It is always gratifying for me to hear people having the most experience with differences in the needs of students whose learning styles vary (sometimes greatly) from those of typical students express this sentiment, which is certainly true for all neurodiverse students, and especially for those on the autism spectrum. For me, it is a confirmation of what I experienced as an undiagnosed autistic going through the educational system many years ago.

I recall to this day that, at parent-teacher meetings and similar events, the most frequent complaint that teachers had about me was that I should participate more in class. At the time, I was considered a gifted student, and today I would be evaluated as “twice-exceptional” once my ASD was identified. As it happens, however, my lack of class participation was attributed to shyness by the teachers and by my family, so not much was done to address it. This is just as well because my reluctant participation had less to do with shyness and much more to do with my not caring about what was being taught, which hardly ever coincided with my specialized interests. On the rare occasions when they did, I suddenly became a very eager participant, raising my hand in class to the point where I can remember coming home with an aching shoulder – so much for shyness! The point here is that, when the material involved one of my interests, I quickly became much more enthusiastic than I usually was. This is now recognized as a classic autistic trait, but at the time (about a half-century ago) was not at all understood.

My classification as a “gifted” student was largely based on standardized test results, and on my prolific ability to remember facts – whenever they involved anything of interest to me, my knowledge of such was virtually encyclopedic. This was further complicated by the fact that my interests, which largely involved anything electrical, mechanical, or electronic and, more generally, things that are today classified as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), are considered exceedingly difficult by many. Once again, it is now evident that I had the common autistic trait of strong “splinter skills” which, fortuitously, coincided with those the educational system evaluated me for. Although I was always successful as a student, due to the lofty expectations and demands of family, teachers, and others authority figures, this was often with great reluctance on my part, as I was neither interested in nor cared about much of what was being taught in school.

Although I am regarded as a “success story,” the truth is that, had just a few things gone differently for me, my life could easily have been quite different indeed. Also, even as my experiences, let alone my outcomes, are not especially common within the autism community, they still serve to illustrate many of the issues that often concern students on the autism spectrum. While I have no formal background in education, I am nevertheless very aware, because of my own experiences, of the fact that students have different learning styles, and best respond to different teaching methods. Once again, this is especially true for those on the autism spectrum.

The Classroom as a Collective

One feature of classroom education, probably for as long as it has existed, is that it is a shared experience. Even as individual effort is demanded of each student, great emphasis is nevertheless placed on the collective experience of the class. Students are expected to be part of this collective and treat their individual efforts as such. For the autistic student, who is often oblivious to many aspects of their social environment, this can be exceedingly difficult if at all possible, and they are poorly served by such expectations.

More specifically, the same curriculum is assigned for all students, and taught to all in the same manner; in other words, “one size fits all.” Autistic students are often characterized by widely divergent abilities in different areas and, of course, by very intense, focused, and specialized interests. When I was a student, I recall that great emphasis was placed on the ideal of “well-roundedness” – in other words, that knowledge and abilities should be equally well-developed in many diverse areas. While this may be a desirable goal in principle, it is, for the autistic student, at best a very unpleasant experience and unrealistic expectation, and at worst a recipe for disaster. For such students, the fact that they will always be significantly stronger, and reach higher attainments, in some areas than in others, should be taken as a given and not as something to be overcome at all costs.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that learning styles of autistics differ not only from those of typical peers, but often from those of other autistics. A substantial amount of individual consideration must be given to autistic students if they are to succeed in the classroom. Also, the expectation that autistic students attain comparable achievement in different areas or subjects needs to be completely discarded.

Setting Appropriate Goals

Once a student is identified as on the spectrum (or having learning differences), expectations must be adjusted accordingly. Intelligence and ability can no longer be treated as having just one dimension, and ASD students need to be evaluated for individual talents as well as deficits. Instruction should be tailored to ability in each specific area, and objectives set accordingly. The advent of Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) has made this more feasible than it was in the past, and the learning differences of autistic students must be understood and used to develop plans that take these into account.

A common preconception that I have frequently encountered, and that I personally faced during much of my life, is the notion that certain areas or subjects are inherently more difficult than others, and that this must be true for everyone. While such may be the case for much of the typical population (even then, I have my doubts), it is especially not true for the ASD population. I have on numerous occasions heard a teacher or education professional express exasperation with a student on the autism spectrum who had phenomenal talent in one area (usually considered difficult or unusual) yet had substantial deficits in skills that are so basic and fundamental as to usually be mastered at a significantly younger age than that of the student.

This is certainly true of my own experience. In high school, my favorite (and, more significantly, easiest) subjects were physics and trigonometry. Many people consider these to be the most difficult subjects they ever encounter and are shocked when I tell them that such things as literature and poetry (much easier in their estimation) were completely over my head. I regard it as a miracle that I was able to somehow pass and even excel in classes involving material that I had no real understanding of but was able to learn (with much unpleasantness) well enough to get through the coursework. I have long advocated for the use of widely varying levels of instruction in different areas for ASD students. In the lower grades, this can be done using IEPs and, in the higher grades, by assigning the same student to honors classes (or even at a local college) in areas of high ability, and remedial classes in very deficient areas. In other words, “one size does not fit all.”

What You Don’t Learn in School

Of course, the areas of greatest deficit for many autistics involve social skills and daily living skills. Interestingly, both are considered so basic that they were (and are) rarely taught in school – you are expected to somehow learn these on your own. While most of the typical population manages to do so, such is not the case for many autistics. They need to be taught these skills in an explicit manner, just as they are instructed in the traditional ones of reading, writing, arithmetic, and other academic subjects. Additionally, there is the problem of “hidden curricula” that everyone is expected to learn but are not officially or formally stated; these are found within the school environment and in almost every other aspect of or setting in life and continue to proliferate. It is interesting to observe that many of the areas where autistics are deficient are precisely those that are not taught in schools.

This suggests both the nature of and the solution to such challenges: autistics, regardless of cognitive intelligence or academic talent, need to be instructed in these areas, which must become as integral a part of their education as any academic subject. Also, other non-school deficits that may occur in individual autistics need to be identified and dealt with as appropriate. Going even further, some of these may turn out to be shared challenges that have yet to be identified, let alone recognized, for large numbers of autistics.

Powerful Motivators

I have long believed that the specialized interests of an autistic person constitute what is probably the most powerful motivational tool for education in existence anywhere. Consequently, these intense and focused interests, rather than being discouraged as they were during the early history of autism, need to be capitalized on as much as possible. This is especially true if the interest is one that can lead to a profession or occupation, or to more advanced academic studies. Given the difficulty that so many autistics encounter with finding employment, these interests often constitute the best if not the only hope for gainful employment and even a productive and rewarding career that they have.

With many autistics, however, the interest, impressive though attainments in it may be, is of little or no practical value apart from its own sake. In such cases, though, it can be used as a motivational tool in educational settings. A simple example involves a child with a strong interest in trains – a common autistic interest if there ever was one! For such an individual, math examples can be presented using trains, which can also be used for assigned problems. The same can be done with science, using trains to illustrate mechanical principles and even the operation of an engine. It can also be done for history, explaining the role that railroads played in the settlement of the American frontier, as well as other examples. The use of such, if nothing else, may make for the student more palatable a subject in which they would otherwise have little or no interest, and thereby help motivate them to learn it. In some cases, this exposure to other material might even result in their developing a new interest – a truly positive outcome indeed.

In cases where the interest is of dubious value, it may nevertheless entail skills that can be of use in more productive pursuits. For example, having an extensive knowledge of trivia that is of no practical use implies an immense capacity for factual knowledge. If such an ability can be generalized to a field of greater importance or practical value, it can lead to academic and perhaps subsequently to employment success.

In my own experience, I was always good at math, but not particularly interested in it until I learned of its use in electronics and physics (both of which were special interests), after which I became a “math fiend” and devoured the advanced courses which I needed to become an engineer. Clearly, the road to educational and employment success for autistics, when attainable, often begins with their specialized interests.

The Value of Education

The importance of education has long been observed to lie not merely in the specific knowledge and skills that are acquired, but in the development of the mind to address the numerous and diverse challenges that the student will subsequently face in life. In other words, the subjects that are taught in school may not be of much (if any) significance to a person’s life, but the process of learning them will impart ways of thinking that may later be of immense value. This should, we hope, be as true for autistics as for the typical population. While the fundamental goals may be the same for everyone, the path towards reaching them will vary greatly among individuals. This is especially true for those on the autism spectrum.

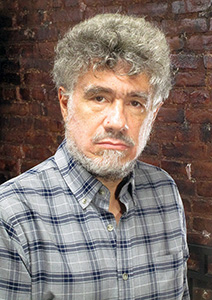

Karl Wittig, PE, is Advisory Board Chair for Aspies for Social Success (AFSS). Karl may be contacted at kwittig@earthlink.net.

[…] range of symptoms, strengths, and weaknesses, so parents should avoid explaining autism as a “one size fits all” experience, Danielson […]

[…] https://autismspectrumnews.org/autism-and-education-one-size-does-not-fit-all/ […]