It is never too early to prepare for any skill, but especially skills needed to live independently. Many young adults feel that moving out on their own is a rite of passage, whether that be attending college to live in a dormitory, renting their own apartment, buying their first home, among many other independent living situations. Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are far less likely to participate in this rite of passage and sense of accomplishment as reported by Anderson, Shattuck, Cooper, Roux, and Wagner (2014). The cases of Autism Spectrum Disorder are rising at an alarming rate. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports 1 in 54 cases in America as of 2016, rising from 1 in 150 in 2000. The ability for our country to adapt and guide these individuals to be productive members of society and live a quality life is a tremendous task. With diagnostic evaluations starting in infancy, the ability for qualified professionals, working alongside families, to assist in learning functional living skills is paramount. The earlier we can begin strengthening their communication, social, and adaptive living skills repertoires, the better prepared they will be for their adult life.

In their study on post-high school living situations among adults with disabilities, Anderson et al. (2014) found that strong functional living skills and conversational abilities correlated with independent living situations for individuals with ASD. This resonates with what the autism and behavior analytic communities know to be true about adult living. Think about the expertise most self-sufficient, independent adults should have to live in the community: finding and keeping employment, managing time and money, purchasing and preparing food, keeping a healthy hygiene routine, and completing regular chores to maintain a home, to name just a few. Not to mention the need for developed conversational and social skills for healthy friendships, roommates, professional relationships, and even romantic connections. For a person with autism, this repertoire of behaviors may be no easy feat to master. If a team waits until late adolescence, potentially 16 or 17 years of age, to begin teaching interventions on these daily living skills, there may not be adequate time for a young adult to successfully master these skills to then transition to independent living arrangements. Additionally, at the age of 21, the availability of support dramatically declines. Expecting a young adult to learn the necessary skills in just a few years is unrealistic and potentially harmful to their future success.

The intricacies associated with true mastery of adaptive living skills, social skills, and community skills requires an individual to begin practicing the basics at an early age. For example, someone learning to create a budget must first understand monetary values, how to use cash or cards at the store, how much common items cost and even using a banking app on their cell phone or an ATM. Thankfully, ABA programs use assessments such as the Assessment of Functional Living Skills (AFLS) and Essential for Living (EFL) to inform treatment teams of these crucial aspects of adult life: toileting, health & safety, housekeeping, social awareness, money, living with others, requesting, acceptance, and following directions (Partington, J.W., 2012; McGreevy, Fry, & Cornwall, 2014). Appropriate programming based on community participation and home living ensures that a child is getting the well-rounded preparation they need for years beyond childhood service availability. Targeting community living competence early throughout ABA intervention programming in the most natural setting possible could promote successful long-term outcomes for the individual into adulthood.

One component of early services that is sometimes overlooked, although essential, is parent and caregiver training. Parents and caregivers play a key role in the treatment of their child for their entire life, long after intensive childhood services. Therefore, practitioners need to effectively equip parents with the knowledge and fundamental skills necessary to successfully implement Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) interventions. Given that the number of individuals diagnosed with ASD has risen since the 1990’s, leading to more adults in need of services, it is now more critical than ever that parents are educated on the basics from the start (Anderson et al., 2014). Giving parents the skill set they need early on will provide individuals with ASD more opportunities for learning, aiding in transitional and independent living further down the road.

The most effective way practitioners can assist parents and caregivers in acquiring these skills is by training using Behavior Skills Training (BST). A study conducted by Lavie and Sturmey (2002) noted the effectiveness of behavior skills training on rapidly teaching non-behavior specialists aspects of ABA. This approach provides opportunities for parents to demonstrate basic skills through rationale, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback. If parents are equipped with the fundamentals early on (e.g., reinforcement, antecedent management, extinction, function-based treatments) then the skills the learners acquire can be practiced with fidelity more consistently over time. More intensive teaching and practice will ultimately award them a greater chance that crucial skills will generalize to new environments and people. This generalization or carry over of skills needs to occur early for individuals living with ASD so that when they reach late adolescence and early adulthood, they can lead more meaningful and independent lives.

In essence, the key to a successful, quality life as an adult begins as a child. Many factors come into play when developing an ABA treatment program at a young age, however, the continuous strive for independence across all skills is imperative. Creating a well-rounded program that includes a variety of skills throughout the individual’s treatment can increase proficiency and ensure that the fundamental skills are acquired early on.

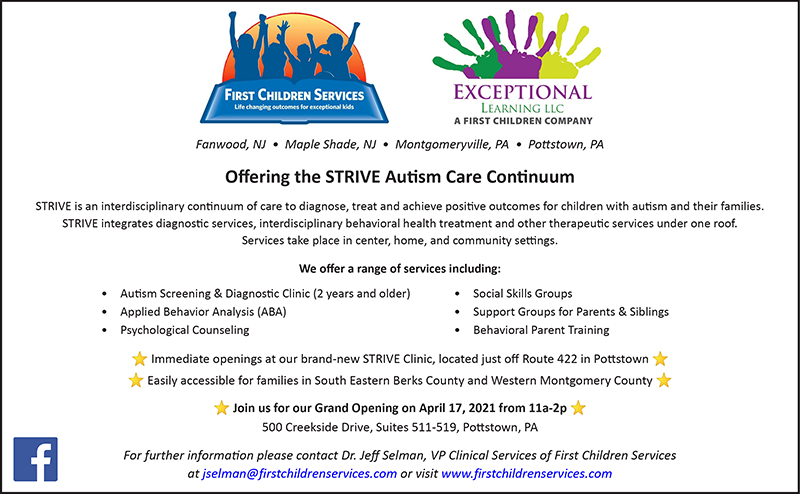

Samantha Smith, MS Ed, BCBA, LBS-PA, is Clinical Supervisor, Rebecca Miller, MS, RBT, is a Registered Behavior Technician, and Julia Robertson, MS Ed, QASP-S, RBT, is a Registered Behavior Technician and Social Media Coordinator at Exceptional Learning, A First Children Company. For further information please contact Dr. Jeff Selman, VP Clinical Services of First Children Services at jselman@firstchildrenservices.com or visit www.firstchildrenservices.com.

References

Anderson, K. A., Shattuck, P. T., Cooper, B. P., Roux, A. M., & Wagner, M. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of postsecondary residential status among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 18(5), 562-570.

Key findings: Cdc releases first estimates of the number of adults living with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. (2020, April 27). Retrieved February 17, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/features/adults-living-with-autism-spectrum-disorder.html

Lavie, T. & Sturmey, P. (2002). Training staff to conduct a paired-stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 35(3), 209-211.

McGreevy, P., Fry, T., & Cornwall, C. (2014). Essential for Living: A communication, behavior and functional skills assessment, curriculum and teaching manual for children and adults with moderate-to-severe disabilities. Winter Park, FL: Patrick McGreevy, Ph. D., P.A.

Partington, J. W. (2012). The assessment of functional living skills. Marietta, GA: Stimulus Publications.