It is important for children with autism and intellectual disabilities to remain living at home, or in the least restrictive environment with appropriate supports, whenever possible. However, at times, a child’s challenging behaviors can pose such a significant threat to themselves or others, it is necessary for that child to live away from home or in a Residential Treatment Facility (RTF) until they can be supported safely in their home again. Such environments offer specialized treatments, expert evaluation, and state-of-the-art safety protocols. They also offer hope that such specialized intervention can ultimately lead to a return to home or to a much less restrictive environment. Ideally, children leave the RTF with a much more nuanced understanding of their behaviors, with a behavioral plan and medication package that is most effective, with greater independence and self-care skills, and with coping skills and supports that ensure their successful reunification with their family, school and community.

Outcomes That Matter

For a residential treatment facility to be successful, effective treatments must be utilized (e.g., Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Bowden, 2018), and these treatments must be delivered within an overall context of humane care. In addition, intervention must be oriented toward outcomes that matter; in other words, the focus should be on changes that make real world differences in the lives of children and families. Organizations must strive to provide high quality staff training (e.g., Henley & DiGennaro Reed, 2015) and must build partnerships with families that are characterized by compassionate care, sensitivity, and individualization.

Perhaps the most important elements are the focus on effective and humane treatment, and on the achievement of significant change through individualized behavior intervention. In 1988, Van Houten and colleagues noted that services within the field of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) were “developed, evaluated, and refined” (p. 381), and asserted that behavior analysts are obligated to provide the most effective treatment that is available within the field. Indeed, within behavior analytic intervention, there has been a long-standing focus on effecting socially significant change through treatment (e.g., Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968). The Professional and Ethical Compliance Code (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2014) specified that clients have a right to effective treatment. What is meant by effective treatment? Generally speaking, it must include increases in adaptive skills, reductions in challenging behaviors, high levels of integration within the child’s community, and high indicators on quality of life measures.

Specifically, residential providers should be held accountable for improvements in quality of life (e.g., Verdugo, Navas, Gómez, & Schalock, 2012) such as the provision of choice and the accommodation of preferences, high levels of individually tailored community integration, and skill building to increase education exposure and employability. When children have treatment goals that address successful community integration and adaptive skill building, their quality of life is improved and they are better prepared to return to their home environment.

Other elements of quality of life include meaningful engagement and meaningful interaction. All children in the treatment setting need to be engaged in tasks that they enjoy and that are meaningful to them individually, as opposed to activities that only satisfy the majority of their peer group. If children are lacking in independent or group leisure skills, active programming and goal setting should be geared toward teaching and attaining these skills. In addition, they should be interacting with other residents and with staff members in conversation, shared activities, and special events. RTFs engagement with their surrounding communities is also essential for best outcomes. Children should attend community outings which are preferred, such as a trip to a favorite restaurant, as well as neutral, such as a “house” trip to the local grocery store for supplies.

Meaningful Engagement

To be busy, active, and involved is to be engaged with one’s environment. Engagement is an active process of involvement, and children with disabilities often have deficits in this area of experience. Efforts are made to understand what is interesting to the individual. When interests and preferences are integrated into treatment, assent for treatment generally increases. There are many opportunities for engagement to be fostered in the identification of preferred educational tasks, preferred vocational tasks, and preferred leisure activities. Engagement can be solitary or it can be social; the key is to enrich the person’s life with experiences, items and activities that they find interesting or activities which increase their independence. Encouraging and teaching activities of daily living, such as completing laundry, food preparation, and self-care tasks can result in a drastic impact on both individuality and improved self-efficacy, while also creating many opportunities for meaningful engagement on a consistent daily basis.

Beneficial Interaction

Social interaction is an extension of engagement. One of the best ways to build interaction skills is through social skills training. Groups are conducted to teach social interaction, game playing, and shared leisure skills. In these groups, staff help to identify peers who might share interests, who might then be encouraged to engage in additional joint activities. Groups sizes are kept small and intimate so individual attention can be provided and goal acquisition can be best managed; however, groups are large enough to allow for a variety of opportunities for socialization and peer to peer engagement. Group games are modified to match all participant skill levels, and activities are created to maximize occasions for communication, joint attention and collective enjoyment and camaraderie. Social salutations and peer recognition are fostered throughout each group meeting. Good decision making, problem solving and useful coping skills are discussed and determined. Skills refined during consistent group gatherings are also tracked and managed outside of the group setting. Taking advantage of naturally occurring social situations throughout the house/unit, at school, and in community environments is critical to acquiring and generalizing beneficial social skills, and to maintaining them.

Family Involvement

Family members are often lacking in hope when their child first enters an RTF setting. The placement likely follows many failed placements and a recent history of escalating problems, often times resulting in an emergent need for police involvement and psychiatric care. When working with family members, it is important to empower them. Many families have had a history of ineffectively interacting with their child, often being unable to connect or to manage challenging behaviors. Building a sense of efficacy is important, as it can foster a sense of what is possible in managing the child’s behavior post-discharge. During the residential stay, families are invited to formal and informal contexts in which such skills can be fostered.

Additionally, RTF providers must ensure that the clinical programming is culturally sensitive (Boel-Studt & Tobia, 2016). Barriers to understanding must be removed, and information must be presented in ways that help the family to understand and participate in the selection of treatment priorities. Both participants and their families are positively influenced by the extent to which cultural sensitivity is embedded into goal selection, instructional procedures, family involvement, and individualized treatment.

Family members who are able to effectively demonstrate the skills and foresight to consistently prepare their home environment for success and/or manage escalating situations at mild to moderate levels of intensity set themselves up for a more successful transition from the RTF back to the home environment. It is also imperative that family members adopt the individualized behavioral plan in accompaniment with the most effective medication package. Constant medication regimens and other factors, such as adequate sleep cycles, balanced diets and exercise, are all contributing factors for caregivers to consider and appreciate.

Summary

In conclusion, successful RTF’s require an unwavering commitment to honor the rights and promote the dignity of those entrusted in their care, to provide effective, culturally sensitive, individualized behavioral intervention, and to monitor success at individual and organizational levels with metrics that matter. Core elements of effective intervention include the provision of meaningful activities and interactions. Ultimately, enhancing quality of life, providing a therapeutic, yet structured environment, and minimizing restrictions on personal liberty are the ultimate outcomes. Social skills training and community integration are beneficial components to each reunification plan. Family engagement, and parent training help ensure a smoother transition back to the home environment and/or the ability to continue to develop and extend safe relationships within the family. These gains are achievable in a comprehensive treatment model that evaluates success with a wide lens. The extent to which RTFs are seen as viable and effective providers of intensive services for uniquely challenging clinical problems and populations will be determined by the ability to focus on outcomes that matter, on services that support dignity, and on the prioritization of engagement and connection for the children served in these settings.

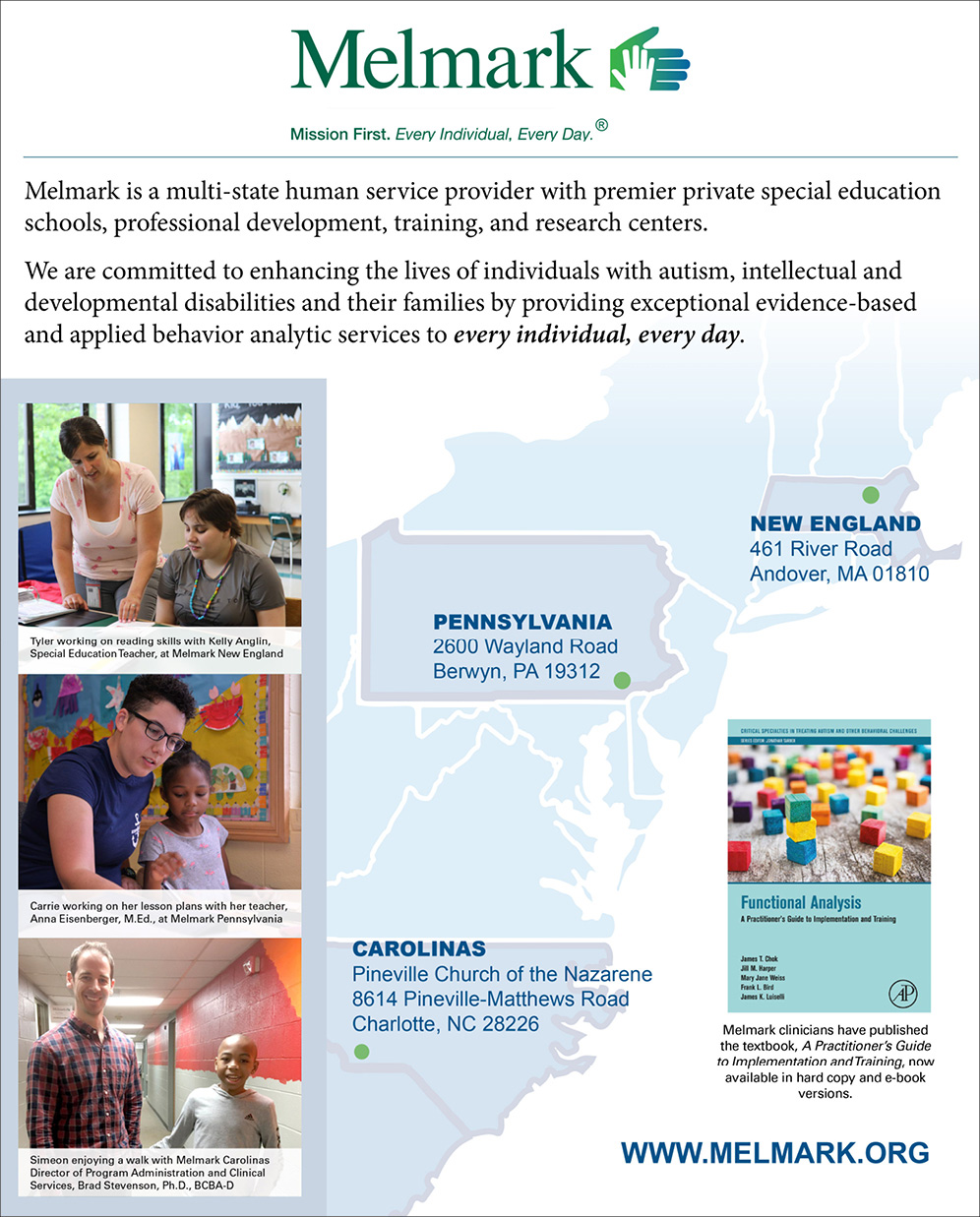

Karen Parenti, MS, PsyD, is Executive Director at Melmark PA. Jen Mucellin, MA, BCBA, is Director of the children’s residential treatment facility, and Mary Jane Weiss, PhD, BCBA-D, LABA, is Executive Director of Research at Melmark. For more information, please visit www.melmark.org.

References

Baer, D. M, Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 91-97.

Boel-Studt, S. M., & Tobia, L. (2016). A Review of Trends, Research, and Recommendations for Strengthening the Evidence-Base and Quality of Residential Group Care, Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33:1, 13-35, DOI: 10.1080/0886571X.2016.1175995

Chance, S., Dickson, D., Marrone Bennett, P., and Stone., S. (2010). Unlocking the doors: How fundamental changes in residential care can improve the ways we help children and families.” Residential Treatment for Children & Youth ,27(2):127–48.

Henley, A. J.,& DiGennaro Reed, F. D. (2015). Should you order the feedback sandwich? Efficacy of feedback sequence and timing, Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 35:3-4, 321-335, DOI: 10.1080/01608061.2015.1093057

James, S., Thompson, R. W., & Ringle, J. L. (2017). The implementation of evidence-based practices in residential care: Outcomes, processes, and barriers. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426616687083

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., & Bowden, S. C. (2018). Why evidenced-based practice isn’t enough: A call for science-based practice. The Behavior Therapist, Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, 41(1), 1.

Slocum, T. A., Detrich, R., Wilczynski, S. M., Spencer, T. D., Lewis, T., & Wolfe, K. (2014). The evidence-based practice of applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 37(1), 41-56. Doi:10.1007/s40614-014-0005-2

Van Houten, R., Axelrod, S., Bailey, J. S., Favel, J. E., Foxx, R. M., Iwata, B. A., & Lovaas, O. I. (1988). The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 21, 381-384.

Whittaker, J. K., Holmes, L., del Valle, J. F., Ainsworth, F., Andreassen, T., Anglin, J., … Zeira, A. (2016). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: A consensus statement of the international work group on therapeutic residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33, 89–106.