If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a country to provide lifelong supports for someone with autism. Parents, school districts, and local, state and federal governments need to collaborate to ensure that individuals on the autism spectrum are provided with programs designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living. Standard best practices for educational programs for students on the autism spectrum have been established for decades; educational professionals know what constitutes an appropriate program, and how to individualize it for each student. The issue is how parents and school districts can best support each other in providing these students with what they need.

Let’s start with educational eligibility. If a child has an autism diagnosis, it is important for autism to also be the educational eligibility on the IEP, rather than speech and language or other health impairment. Having consistency between the medical diagnosis and the educational eligibility helps to ensure that the right placement, services, and program accommodations are put in place. An autism eligibility on the IEP also eases the task of obtaining services outside of school.

If a child is suspected to be on the autism spectrum but has not yet been formally diagnosed, it is very important that the school district help parents to have their child appropriately assessed, and as early as possible. Educational eligibility under Autism is not the same as a diagnosis from a clinical psychologist or medical professional. A student does not even require an autism diagnosis to meet the autism educational eligibility, but most school districts are more comfortable agreeing to an autism classification once the diagnosis has been made.

Most, if not all, students with autism share at least three common areas of deficit that may interfere with learning: 1) Behavior, 2) Sensory integration dysfunction and 3) Communication impairment. Each child’s IEP must include goals and accommodations pertaining to all three of these areas.

1) Behavior is all a matter of degree. Issues of task avoidance, learned helplessness, and passive noncompliance need to be addressed as well, with positive behavior strategies that capitalize on motivating the child. There always should be behavioral goals, not limited to severe acting out and noncompliant behavior. There also must be social and emotional goals with regard to peer relations, socially appropriate behavior, perspective taking, mutual respect, and class participation.

2) Sensory issues, whether seeking out sensory input and/or avoiding it, can easily be mistaken for behavior. It is critical for students with autism to always receive occupational therapy, both as a direct service and as classroom consultation, so that teachers and other classroom staff can provide the student with those sensory strategies needed in order for the student to maintain the appropriate level of arousal for learning. Students must also learn how to monitor their own needs and seek out necessary input to lessen anxiety and maintain attention. Classroom-based programs such as the Alert Program and Stick Kids are inexpensive to use, and very empowering for both teacher and student. Occupational therapists also address fine motor, motor planning, muscle tone, and visual motor skills. As these often remain areas of relative weakness throughout a student’s career, it makes sense to keep occupational therapy on the IEP.

3) Communication pertains not only to expressive and receptive language, but also pragmatic and nonverbal skills. In addition to being able to communicate what they know, students must be able to communicate what they need. Even if a child with autism demonstrates a sophisticated vocabulary with regard to specific areas of interest, there still may be areas of relative deficit that need to be addressed. There is often the lack of desire to communicate with others because the value of doing so is not recognized by the child. Social interaction cannot be limited to group counseling and speech therapy pullouts. It also must be generalized, and the goals worked on throughout the day in a variety of settings, such as the classroom, lunch, recess, and physical education. Strategies needed may include raised affect, humor/nonsense, and withholding of desired outcome unless requested.

Augmentative communication devices do not take the place of speech but rather serve as a means of communication that encourages verbalization while preventing frustration caused by the inability to make oneself understood. Augmentative communication must always be used reciprocally, by both student and adult, whether it be a picture exchange system, or an iPad with Touch Chat. Collaboration is needed by the entire team – teacher, speech therapist, occupational therapist, behaviorist and parents – in order to achieve progress.

The physical process of writing can be very arduous for students with poor fine motor skills and low endurance. Assistive technology (AT), such as keyboarding and semantic mapping software, should be used consistently. AT can also address poor executive functioning skills by helping to keep students organized and set priorities. Occupational therapists and learning specialists must keep current on what is available and what works best for each student.

Effective communication between home and school is essential in order to maintain consistency and measure success. Students with autism are not wonderful reporters, so the only way for families to know what has occurred, what they need to do for homework, or if they handed in their homework, is to have consistent daily communication, either in a notebook or via email. It can prevent potential task avoidance (“I don’t have any homework” or “I left my homework at home”), alert school staff to changes parents observe in behavior, or even let the school know if the child has had a bad night. It is also important to share successes and collaborate on positives. It can carry over topics for conversation (“We went to the beach this weekend,” “We had a play date with a peer,” etc.).

Success for children with autism is a team effort – in school, at home, and in the community. Parents need to be informed of services available to them at home and in the community and be encouraged to apply for them. Families should be encouraged to seek out parent support groups and therapeutic services, and to become active in the school district’s special education PTA. This helps parents to stay informed, feel empowered, and less isolated and overwhelmed.

It is important to always raise the level of expectation with regard to skill acquisition. Once a skill has been demonstrated – even once! – it is important to the raise the bar. The balancing act comes in knowing when to push students to exceed their comfort level, and to figure out how much of what one sees is task avoidant behavior rather than inability. We need to keep in mind that many of the skills naturally demonstrated by other students are not necessarily outside the grasp of a child with autism. Longitudinal studies indicate that there is often what appears to be a slower rate of learning, but that the capacity for learning is lifelong. There is no plateau, and many skills can be developed long after what appears age appropriate.

The same student may also demonstrate different rates of growth at various times: academic, social and emotional, and physical. We see this in many students, but it seems to be even more profound in those with autism. It is therefore important to capitalize on the areas of strength, while intensifying efforts to address the areas of weakness.

Many students with an eligibility of autism are relegated to unnecessarily restrictive settings throughout their day, having little or no meaningful access to typical peers. Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) must be provided in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). The value of typical peer modeling is inestimable, and all students should have meaningful time each day with general education students, not just sitting at a lunch table with one’s class in the cafeteria or having adaptive physical education in a corner of the gym separately from the general education students. Facilitated mainstreaming opportunities can be provided in countless ways: in elective classes, lunch and physical education, and classes where the student has a strong interest or particular academic strength. There is also reverse mainstreaming, where general education students are brought into special education classrooms. Mentor or buddy programs can be developed, focusing on activities of mutual interest such as computer games, animals, history, or transportation. Lunch groups and after-school clubs can be formed to include special needs and general education students. Students can be teamed up as study buddies, library buddies, and homework buddies.

Students with autism are too frequently victimized by other students. Teasing and bullying cannot be allowed in our public schools. The more students with disabilities are part of the school in every way, the more other students will be accepting, and our children will be valued. The message for students that accepting and helping others is desirable behavior that they should want to emulate must come from their peers, not just staff. I once observed a child about to pick on someone on an elementary school playground, when another boy headed him off, saying, “I am so not OK with that!” Grammar aside, the message was clear, and the incident was averted. We need to imbue all students with the concept of social responsibility – that, as a society, we need to support each other. As that boy stated when his teacher praised him for intervening, “Well, everybody’s got something.” How true.

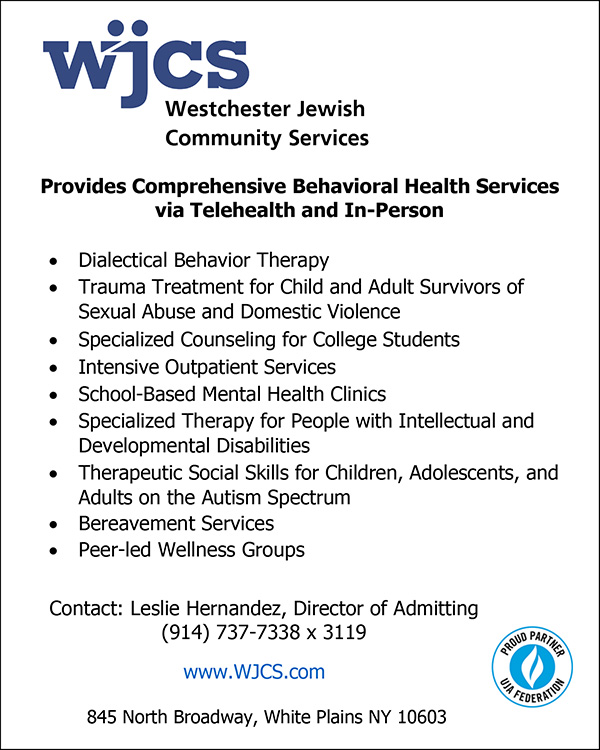

Lee Englander has been a special education advocate for over twenty-five years. Westchester Jewish Community Services (WJCS) has served families in Westchester County, NY since 1943.