During the COVID-19 pandemic, many children are falling behind due to compromises in therapy and education services. Children with disabilities who previously had stable access to regular in-person therapy are losing that access, leading to regression (Jones, 2020). While tele-care and remote video services have supplemented typically developing children, those with challenges have difficulty establishing rapport and maintaining engagement during video conferencing (Akamoglu, 2018). In spite of this unprecedented challenge, some children are maintaining and improving with Robot-Assisted Instruction or RAI.

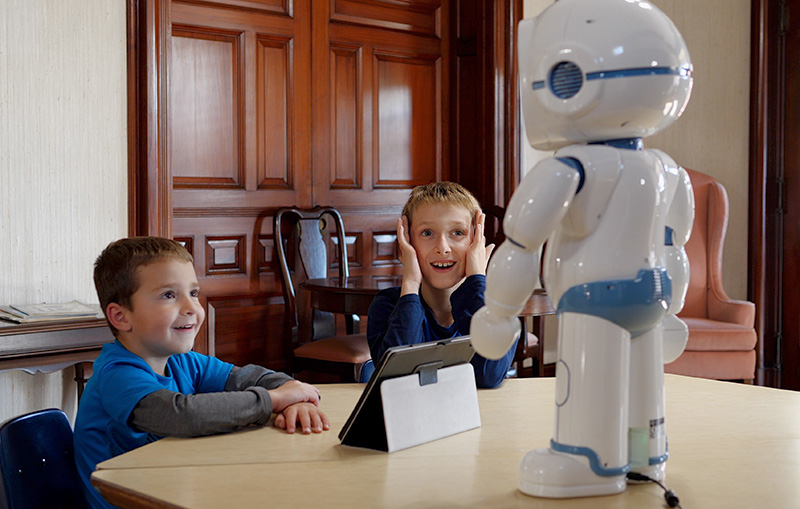

The iPal robot from MOVIA Robotics is 3ft tall, can move around the room on a motorized base, and can stand in front of a classroom or group of children. The iPal can lead groups through physical activities, story-telling or other lessons, and has additional apps for STEM education. (Credit: Maring Visuals)

“[The RAI system] has become a bridge between school and home services. It has allowed him to practice new tasks outside of those formal settings which has then given him the ability to take those newly learned skills back to the tele-school environment to showcase what he has learned.”

– David V., father of a 5-year-old boy with Autism Spectrum Disorder

RAI is a technique where a small, friendly robot is used to deliver instruction to children with autism. The robot leads the child through games and activities designed to teach learning readiness, activities for daily living, social-emotional and other skills. The robot exhibits social traits while interacting and engaging with the child. Children enjoy playing with the robot, often spending 30 to 40 minutes participating in lessons and other educational activities.

Robots are simple and yet are perceived as social entities by children. This allows children with autism an opportunity to practice social interactions in a safe environment and take chances practicing new skills before they’ve mastered them. Children want to play with the robots, enabling the robot to be the intervention and the reward, leading to greater access to their curriculum. The robots are very even in their speech with no judgment or negative reinforcement. They are very patient and predictable, which builds comfort, confidence, and increases attention span.

For children with developmental delays such as autism, early intervention, including consistency and continuity of care, is critical. Without early intervention, children struggle to develop the skills needed for school, work, and relationships, leading to lifelong disparities in achievement, income, and quality of life (van Agt, 2005). This places a large burden on families to find services during a narrowing window of early childhood opportunity, which has become unbearably stressful during the pandemic as many families are struggling to find consistency and continuity of care.

RAI has been used successfully in classrooms for years with growing acceptance by specialists and administrators who see the benefits for children with autism. Through multiple collaborations between educators and RAI developers, content has been tailored to align with the educational objectives, programs, and individualize educational plan (IEP) goals used in the special education departments. This has enabled educational specialists to easily integrate RAI with their other course work. The benefits include increased engagement, verbalizations, confidence, skill acquisition and generalization to socialization with others. These benefits have been published widely in literature for over the past decade or more (Cabibihan, 2013, Scassellati 2007, Scassellati 2018, Robins, 2005, Ferrari, 2009, Chung, 2019). This research has been accompanied by increasing attention from the clinical community to further leverage this important opportunity (Rabbitt, 2015).

“Students demonstrated skill attainment on targeted skills in attention, listening skills, reading comprehension, social skills, coping mechanisms, articulation, and reciprocal communication…students demonstrated generalization and carry over into other learning environments such as the classroom, the playground, and even at home.”

– Glenn McGrath, Former Director and Education Consultant in Special Education

Kebbi is MOVIA’s first “HomePal.” It is an Educational Robot that integrates artificial intelligence, software, and hardware technology to provide a variety of facial expressions, body movements, and communicative interactions. Kebbi provides a unique set of capabilities that work very well for the home or school environment. These interactive capabilities provide users with a heartwarming and educational experience. (Credit: Maring Visuals)

This technology has been adapted successfully to the needs in the home environment due to the COVID-19 school closures. Robotic systems have been historically complex and difficult to use; however, recent advances have enabled systems that are simple and easy to use. Lesson plans can be created by a clinician or teacher and downloaded to the system. Parents can easily run content that is tailored to their child. The child’s performance can be reviewed by the specialist and then the intervention program can be modified. This enables the parent to provide custom interventions even when a trained professional is not available.

Children with ASD act in ways that are often very different from typically developing children. This can be frustrating for parents who want the best for their children and are trying to provide the best care. With RAI, however, parents are able to use clinically proven methods, such as discrete trial training, very easily. The lessons and activities that the robot delivers are designed using evidence-based techniques. The level of complexity of the activity, as well as the amount of prompting that the robot gives, can be adjusted to suit the individual child. The adjustments can be made by either the parent or the remote specialist. The parent and specialist work as a team to deliver the intervention to the child. This technique gives the parents confidence that they are providing appropriate intervention that is aligned with the interventions the child is receiving at school or in clinical settings.

Responses to these RAI systems have been profound, bringing some parents to tears, seeing their child confidently attending and engaging and communicating as rarely or never before.

Activities and interventions with the robots encompass a full range of social emotional, academic and cognitive goals, similar to those identified in the child’s IEP. For example, the systems can provide movement games that teach imitation and turn taking or role plays where the child can practice simple social interactions like saying hello and goodbye or joining a group. In RAI systems, in addition to the robot directing the child, a tablet is used to provide educational material to the child and to provide the child with complex interactions such as moving objects to solve a task or engaging with visual concepts. Academic lessons can be taught from introductory level to more advanced, with the content scaffolding on itself so that the child can move to mastery within their IEP goals.

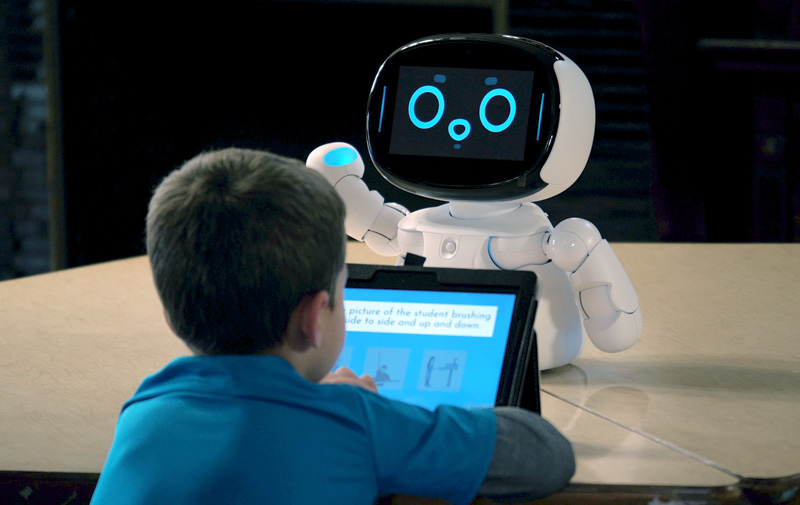

The QT robot from MOVIA Robotics is a charming tabletop friend with a friendly face. It can present animated expressions and simple movements that engage and educate children. (Credit: Maring Visuals)

While some may be concerned about robots “replacing human relationships,” this is not at all the case with RAI. The robots are a tool for an educator, therapist or parent to use, not a replacement for human care. The RAI control interface provides a smooth delivery for the tailored intervention, but ultimately the facilitator has complete control over moderating the child’s experience and assuring individual goals are met. The system is easily used with the direction of the child’s board-certified behavioral analyst (BCBA), speech and language pathologist (SLP), occupational therapist (OT), or education professional to align lessons with IEP goals and maintain progress at home. Families typically use the robots 3-5 times per week. Sessions typically range between 5 minutes and 45 minutes based on the needs and goals of the child.

Experienced educational therapists have discovered the value of RAI, both in the school setting and in the home.

“For [client, age 7 with Autism,] using the robot increases attention, decreases impulsivity, improves engagement in learning, and helps with generalization and maintenance…Improvements have been joint attention, turn taking, patience, following directions, social skills, pragmatic language, maintaining skills…It has been life changing for myself… and I have really enjoyed seeing the robot’s interaction with the students and how it has changed their lives.”

– Kristen Whoolery, Speech Language Pathologist, Wallingford, CT School District

Continuing the programs at home complements the use of RAI in the school or clinic. Parents detail how their children have progressed through content over months, with reports of generalization, maintenance, and improvement in IEP goals.

“In the few short months since we have started working with Bobby [the robot], our son’s eye contact has improved, he responds to his name more frequently, his functional vocabulary has more than doubled, he will sit/engage in activities for longer periods of time and he even started initiating play with his 1-year-old little brother!”

– Christa A., mother of a 3-year-old boy with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Most importantly, parents have reported how RAI has put their child in a better position to return to school and integrate in the classroom, a valuable ongoing tool for families beyond the pandemic. Whether in the school, in the clinic, or at home, RAI is another tool being used successfully to improve learning for children with autism.

Aubrey A. Shick

Timothy D. Gifford

Timothy D. Gifford is President and Aubrey A. Shick is Head of Product User Experience at MOVIA Robotics, Inc. For more information on how RAI works to improve the lives of children with Autism, please contact MOVIA Robotics, Inc., at the following: www.moviarobotics.com | info@moviarobotics.com | 860-256-4797.

References

van Agt, H. M., Essink-Bot, M. L., van der Stege, H. A., de Ridder-Sluiter, J. G., & de Koning, H. J. (2005). Quality of life of children with language delays. Quality of life research, 14(5), 1345-1355.

Jones, N., Vaughn, S., & Fuchs, L. (2020). Academic Supports for Students with Disabilities. Brief No. 2. EdResearch for Recovery Project.

Akamoglu, Y., Meadan, H., Pearson, J. N., & Cummings, K. (2018). Getting connected: Speech and language pathologists’ perceptions of building rapport via telepractice. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 30(4), 569-585.

Scassellati, B. (2007). How social robots will help us to diagnose, treat, and understand autism. In Robotics research (pp. 552-563). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Scassellati, B., Boccanfuso, L., Huang, C. M., Mademtzi, M., Qin, M., Salomons, N., … & Shic, F. (2018). Improving social skills in children with ASD using a long-term, in-home social robot. Science Robotics, 3(21).

Robins, B., Dautenhahn, K., Te Boekhorst, R., & Billard, A. (2005). Robotic assistants in therapy and education of children with autism: can a small humanoid robot help encourage social interaction skills? Universal access in the information society, 4(2), 105-120.

Ferrari, E., Robins, B., & Dautenhahn, K. (2009). Therapeutic and educational objectives in robot assisted play for children with autism. In RO-MAN 2009-The 18th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (pp. 108-114). IEEE.

Rabbitt, S. M., Kazdin, A. E., & Scassellati, B. (2015). Integrating socially assistive robotics into mental healthcare interventions: Applications and recommendations for expanded use. Clinical psychology review, 35, 35-46.

Cabibihan, J. J., Javed, H., Ang, M., & Aljunied, S. M. (2013). Why robots? A survey on the roles and benefits of social robots in the therapy of children with autism. International journal of social robotics, 5(4), 593-618.

Chung, E. Y. H. (2019). Robotic intervention program for enhancement of social engagement among children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31(4), 419-434.

[…] Read the Article Post navigation […]