Autism has been described, and sometimes defined, as a disorder of communication. This is certainly the case for nonverbal autistics and others who are completely unable to communicate, but it is just as true for those who are articulate and able to express themselves verbally. For them, autism is often, if not usually, a deficit (sometimes serious) in social communication. For many, if not most level 1 autistics of at least average intelligence, who are able to read, write, and otherwise communicate verbally, this deficiency is often not recognized and, as such, never addressed. This does not help the affected autistic since social communications are about the most important form that humans engage in, and the lack of skill in which can be detrimental to the life of an individual.

Teaching Social Communication Skills

Social communication skills, like other skills, need to be learned. This happens through personal experience (sometimes painful) and by explicit instruction, as in a school setting. During much of my life, I believed that the educational system ignored this issue and regarded it as something to be “picked up” in the course of one’s life. For many years, I was very angry about this and felt that my schools had completely failed me in this regard. At least, so I thought.

Later in life, however, I was occasionally told that reading a lot of fiction was of great value in learning to understand others and interact with people. I had always been a slow reader and, like many autistics, read almost entirely non-fiction with only the occasional (of course) science fiction or techno-thriller. I also learned, not long after my diagnosis in late 2000, that autistics often had difficulty with discussions, after reading a story, about what the characters might be thinking or feeling – this was attributed to deficits in theory of mind. Upon reading this, I immediately recalled having had this exact difficulty. I also remembered that when the thoughts and feelings of characters were explicitly stated in a story, I was able to follow, even though it wasn’t particularly easy for me to do so. Later, when these were not articulated but instead became part of the subtext (something that I was completely incapable of discerning), I had absolutely no idea how to make such a determination; to this day, I wonder how I ever got through those classes in school!

This all means that at least this one method of teaching social communication was being used in schools, but because I was completely oblivious to such, it was of no use to me whatsoever. Being a twice-exceptional student, though, I had always received high scores on standardized tests of reading comprehension – usually two to three years above grade level. As it happens, these consist of passages that are always non-fiction and questions about such that almost always concern something explicitly stated in the text and rarely, if ever, in the subtext. Is it any wonder that I did so well on these? Clearly, these tests can measure literal understanding of written material but not much else. I subsequently learned that high reading scores are not uncommon among autistic students, who typically process language very literally. When presented with anything that involved subtext, however, particularly concerning the thoughts, feelings, or motivations of characters, their interactions, or their behavior in social settings, I had no idea what was happening.

Reading good fiction, which includes much of the great literature that is studied in schools as well as that which people read simply for pleasure, provides a form of exposure to different kinds of people and situations (social and otherwise) that one may never have personally experienced but might encounter in the future. This, in turn can prepare the reader for the day when such does happen by providing an abstract form of “script.” For me, as for many other autistics, this largely implicit means of instruction in social communication was of no value whatsoever; it was simply too advanced for my level. As a result, I got little benefit from this form of education; not to mention that the science fiction stories that I sometimes did read were hardly known for realistic character development!

Even for younger autistics, this can present a challenge. There is no shortage of children’s stories, going back (at least) to Aesop’s fables, which teach a moral message; these usually do so in a manner explicit enough to more likely be understood by younger autistics. Unfortunately, such is not the case for stories that involve the thoughts and feelings of others, let alone how people are expected to behave towards and interact with each other. Once again, the need for teaching social communication skills remains unmet.

Tools for Teaching Social Communication

On one occasion, while I was in high school, I came across a pile of discarded educational materials, which I quickly noticed dealt with social situations – these were clearly intended for a much lower academic level. I immediately picked up the entire lot, took it home, and voraciously devoured it that very afternoon. This was unusual for me because, as a slow reader, I rarely read anything so quickly, even when it dealt with my special interests. Clearly, I was nothing less than starving for this kind of information.

Unfortunately, the use of such paraphernalia as the above had been discontinued, given that they were discarded. The same is true for educational films used in earlier decades, some of which dealt with issues related to social communications. Once again, these fell out of favor and even became the subject of ridicule; in college, I once attended a dorm party at which some of these were shown as comedic entertainment! In any case, tools of this nature were eliminated in the schools and effectively replaced with nothing.

For this reason, I was especially gratified when I learned (once again, shortly after my diagnosis) of a methodology called social stories, which depicted a variety of social situations in comic strip form. Remembering my above-described experience, I immediately recognized the value of this technique. When I was growing up, comics were greatly frowned upon, particularly for students of higher ability; even my own family strictly prohibited me from having them. It is ironic that such a tool might have been highly beneficial to me, even if I was attending a science school of very high standing at the time. Years of use attests to the fact that this method is an effective means of teaching social communication skills to a wide variety of autistic individuals.

All autistics need some form of simplified explicit instruction in social communication skills to be provided at appropriate grade levels, regardless of their age, intelligence, or academic ability. Whatever tools are available for this purpose, be they social stories or classes where fictional narratives involving social situations are discussed explicitly and extensively, must be deployed.

Social Communication Skills in the Workplace

As important as it is to develop social communications skills while in school, it is even more important to have them later in life, especially in the workplace. Unfortunately, this is one environment where not only are people expected to have these skills but is the most unforgiving of those who do not. As such, many work situations are generally not suitable for autistics; this is true of many positions that involve dealing with clients or customers and especially true of environments where workplace politics is a dominant part of the culture. As is usually the case, autistics thrive best in situations where they are evaluated and judged on the basis of their skills and talents in areas where they excel. The employer who is willing to accommodate such an individual will often be rewarded with an employee who does exceptionally good work in their area of ability.

Nevertheless, even in the most optimal work situations, it is desirable, if not essential, for autistics to be well-instructed in social communications as needed for their work environment. What is greatly needed are adult versions of the aforementioned tools that are used in school settings (or should be – certainly for autistics, but many non-autistic students would probably benefit from such as well); in particular, any material that deals with issues likely to be encountered in the workplace. The same methods that are used for younger individuals can be adapted for use with adults; once again, this applies to autistics regardless of age, educational attainment, or intelligence. Although some autistics have access to job coaches who can be of great help with this, and even employers who allow such coaching on their work premises, many autistics (perhaps the vast majority) do not. For them, anything that helps improve their skills in this essential area will be of immeasurable value.

My Own Experiences With Communications

For most of my life, communications have presented a variety of challenges. In school, especially in classes such as English and social studies, I always had substantial difficulty with topics that involved nonliteral or social communications. In particular, I could not write fictional stories beyond the most infantile level (and forget about poetry!). Essays, at least where analytical thinking was involved, were less difficult, and on the rare occasions when I was allowed to write about a special interest, I actually did quite well (hardly unexpected). I was able to pursue higher education largely because I attended an engineering college where these subjects were only minimally required.

Early in my career as an electronics engineer in research and development, I was often told, during performance evaluations, that my communication skills needed improvement (along with a few other areas that I later recognized were related to my autism). Over many years, they gradually improved; in particular, I often had to write engineering reports and patent disclosures (for submission to attorneys), which exclusively involved technical writing. Only in this manner was I able to improve my writing skills. With time, I came to recognize some of my bad writing habits: writing very long sentences, using superfluous words, and re-using the same word over and over, among others. I realized that, by going over anything that I wrote at least a few times, I could recognize and correct these, resulting in a higher quality of writing. Incidentally, that includes this very article!

As to spoken communications, I realized, at my job, that when a farewell lunch was given for a departing or retiring employee, and a number of speeches were given in their honor, I had a talent for giving the “funny” speech. In fact, I became so good at this that I was always asked to give such a presentation. This, in turn, prepared me well for giving technical presentations about my work and, eventually, for speaking at the many autism conferences where I talked about my life experiences as an undiagnosed autistic.

In conclusion, the whole area of social communications is one that, especially for undiagnosed autistics (which includes everyone on the spectrum past a certain age), has long, if not completely neglected, gotten far less attention than it deserves and that the autistic community needs.

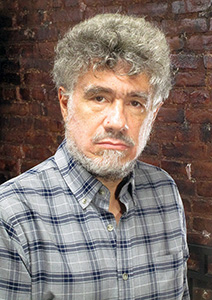

Karl Wittig, PE, is Advisory Board Chair at Aspies For Social Success (AFSS). Karl may be contacted at kwittig@earthlink.net.